The intrepid Suchitra Vijayan is working on a 9,000-mile journey through South Asia, which has taken her to Afghanistan and Pakistan, the disputed territory of Kashmir, and India's borders with Burma and China. What has she learned so far about the effects of borders on human lives?

ALEX WOODSON: Good evening and welcome to the Carnegie Council. I'm Alex Woodson, program coordinator for Carnegie New Leaders. Thank you all for coming out tonight.

I'm very excited for tonight's event. While we will be focusing on South Asia, questions about border and identity have an influence on almost every geopolitical issue these days, and it fits in with one of our overarching themes at Carnegie Council, citizenship and difference.

I'm also excited for tonight's talk because it features two Carnegie New Leaders, Suchitra Vijayan, who you will hear more about in a moment, and our moderator Liana Sterling.

Liana is a senior analyst in intergovernmental relations at the New York City Mayor's Office of Management and Budget, where she covers public health, social, and labor issues that affect New York City. She holds an MPA and an MPH from SIPA [School of International and Public Affairs] and the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University and a BA from Bryn Mawr College. She is also a member of the Carnegie New Leaders Steering Committee.

Thanks again for coming out. Liana, the floor is yours.

LIANA STERLING: Thanks, everyone. Welcome.

I would like to take a moment to introduce Suchitra Vijayan. Suchitra is a writer, photographer, lawyer, and political analyst. She graduated with an LLB in European Union law and was called to bar by the Honourable Society of Inner Temple in 2005. She previously worked for the UN war crimes tribunals for Yugoslavia and Rwanda. She co-founded and was the legal director of Resettlement Legal Aid Project in Cairo that provided legal aid for Iraqi refugees in Egypt.

Suchitra spent the last two years researching and documenting stories along the contentious Durand Line. She was embedded with the ISAF's [International Security Assistance Force] 172 infantry brigade, in Paktika Province, Afghanistan, conducting research on key kinetic terrains in the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

She graduated from Yale in 2012 and is currently working on her project titled Borderlands, along India's borders. The project is conceived as a travelogue chronicling stories along India's borderlands, covering six of India's borders with Pakistan, China, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Burma, part a visual anthropology and part an attempt at understanding the Indian state, its pathologies, and the fringes it governs.

Please join me in welcoming Suchitra.

DiscussionLIANA STERLING: What initally piqued your interest about this project?

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: It all started with my graduate work. When I was in graduate school, I went to Afghanistan for the first time. As you mentioned, I was embedded with the U.S. military at the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, which is the Paktika Province. This is a province that actually borders North Waziristan, South Waziristan, and parts of Baluchistan. Initially I was there to understand what was happening to insurgency and counterinsurgency operations.

Once I got there, I realized that there were a lot more important questions that we were failing to ask. One of them was that we were not taking into account the local productions of history and memory: What do Afghans really think about this?

The second thing is that, even before we talk about grand strategy and these really important things, we were forgetting that this idea of nation-state itself is deeply under question. These are contentious things.

That's how the project initially started, in asking these important but very simple questions that I couldn't find answers to.

Once I graduated, I had these similar questions and actually wanted to ask these same questions in relationship to India. India has one of the longest land frontiers in the world, close to 9,445 miles. Even that number is contentious. It borders, as you mentioned, six countries. Each of India's borders with another country engenders a different kind of conflict.

So what we see here is conflict in the Northeast, which has had insurgency, need for self-determination. Then you look at the India-Bangladesh border. What you really find there is a porous border that's also getting fenced. While the historic nature of this border is not similar to the Mexican-American border, the questions of "who do we let in," "why do we let in these people"—I think those questions of legality and all of that are still very important.

Then you move on to the terrain in Arunachal Pradesh, which is also the contentious place that India is now getting more and more aggressive with China. This place was also the site of the 1962 war. India is increasingly militarizing this region.

Of course, you have the ever-contentious Kashmir, which is not just a question of insurgency or territorial rights between India and Pakistan anymore; it is also the right of the Kashmiri people and their right of self-determination.

I looked at all of them and I said, "How fascinating." I really wanted to understand India, the Indian state, from these perspectives. That's what I have been doing since 2012. It has been quite a journey.

LIANA STERLING: For those who may not be as familiar, do you think you could provide a little bit of a background of the 1947 establishment of the Indian state and the borders as we know it?

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: That year, 1947, is often seen as the watershed moment, and modern Indian history somehow begins from here, or at least is often seen from here. The partition happens as a result of India's need for independence. It is a struggle that dates, depending on who you talk to, between 100 years and 30 years. This movement for self-determination ends up with India gaining freedom, but also India being partitioned into India and Pakistan.

It's one of the biggest population transfers that happened. Sometimes people say close to 10 million people actually moved across. They say over 1 million people died in the process. So what you really see is that the birth of a nation is also a deeply traumatic and bloody history.

But one should also keep in mind that the birth of India is not ahistorical. One has to place this in a much larger context of the colony and the empire and colonial cartographies that continue to wreak havoc in our lives today, whether it's Iraq, whether it's South Sudan, Israel and Palestine. All of this dates back to a much larger sense of what empire did to this world and what carries on from there.

LIANA STERLING: I'm wondering if you could talk a little bit about the significance of what you are doing, which is tracing the border, rather than picking particular places and traveling to them discretely.

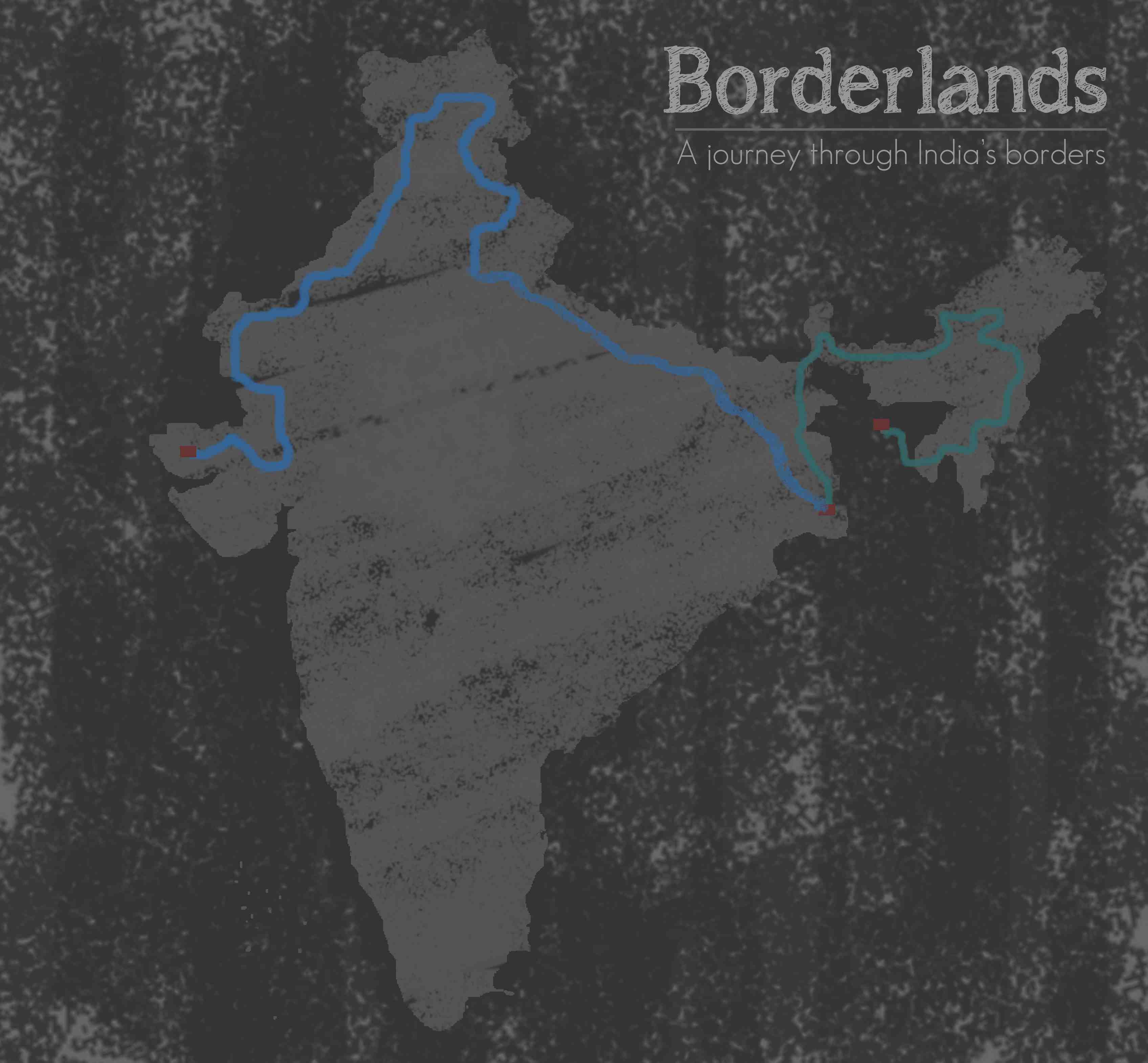

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: The first page is the map. It's part of the journey I took.

The green kind of talks about the first leg of the journey. It is not quite updated. I have also done parts of Kashmir. So that is the physical journey that I've taken. There are still parts of the border with Pakistan that are left.

One of the reasons I wanted to physically travel is because it's extremely important to situate oneself in the historiography of these places. While archives can create political agency, I don't think they give you the kind of human agency that you get to understand while you're in the field.

One of the most fascinating stories—one of the first field interviews I did while being on the road was this young man that I met. Listening to his story, his grandmother—when she was alive, there was only British India. India and Pakistan didn't exist. Through the course of a life, it becomes India and East Pakistan, which is Bangladesh, and then Bangladesh is created. Over his own lifetime, the border that was once porous, where games of international cricket were being played by young boys every day, is being transformed into a fenced society. You have these ubiquitous border security camps growing up.

All of this happened because I had to stop the car and ask him for directions to another BSF [Border Security Force] camp. I think it's incredibly important to have those stories—serendipity has to play a huge role in that.

Also when you travel, you understand the problems of not being able to travel to certain parts of the country. Once I got to Arunachal Pradesh, I was very specifically told that civilians would not be allowed.

I understand that security is important, and often you would have these checkpoints in which you were being stopped by the Indian Army or anybody else in that position of power, who said, "Why are you doing this?" So what you really understand when you travel is that you're also understanding the dynamics of what the local population has to live through.

Those were the reasons why I felt that the actual travel has to happen if one has to really have a conversation about what's happening to these people in these regions.

LIANA STERLING: That leads into my next question, which is whether you can talk about some of the specific vignettes or stories that have been most powerful to you in this journey so far.

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: I'll actually start with a story that is incredibly powerful, especially for jazz lovers in New York. I don't know how many of you know this fantastic jazz musician called Alberta Hunter. There's this road called the Ledo Road that was built by American soldiers in the Second World War in India's North-East. I didn't know about this. I found out about this incredible road that was built by close to 20,000 American soldiers in the South Asian borderlands. When these American soldiers were there building these roads, Alberta Hunter, who was a fantastic jazz musician, travels and sings and entertains the troops, and there is this fantastic visual archive of it.

I was actually quite surprised and fascinated. There are these little jazz stores in which you can still buy these records that were produced at that time.

So while it's not directly related to the idea of India's borderlines, it also tells you this narrative of things that connect from New York to Assam to other places.

For me, the most fascinating story is, when I first got there, as I said, the physical aspect of a border was just so fascinating to me. There are houses in Bangladesh which the international border runs through, so one side of your house is in India, the other side is in Bangladesh. There's this beautiful 13th-century Sufi mosque that has an entrance in India and the exit in another country—then you look at these things and you wonder what really happens. Here are a bunch of people upon whom we have imposed a cartography that makes no sense.

Once I started moving to places like Kashmir, it became incredibly difficult for me to trace the border. Because Kashmir is also one of the world's most militarized zones, the very act of traveling to certain places was very contentious. It's just impossible for you to get access.

Also in these places, the stories are less about the border itself and they are more about the what happens during the insurgencies. Some figures put the number of boys and men who have been disappeared at close to 80,000. You have these stories of torture. What you really see in all of the stories that brings them together is that, while the creation of the Indian state and the partition happened a very long time ago, there are people who experience this—it's continuous and it's ongoing.

I think those were the main themes that ran through so many of these stories.

LIANA STERLING: What do you see are the policy implications for South Asia from this project?

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: One of the things that keeps coming up over and over again is that we have this idea of these borders as contested borders. Soon what follows are ideas of nation-building and state-building, and very soon we are in the realm of failed states, and then very soon we are in this idea of intervention to protect these failed states. These are all very contentious labels, and if not causation, there seems to be some kind of correlation that seems to be happening. I think we are in the moment when we need to go back to the basics and start questioning these assumptions and how to start understanding these assumptions.

One of the things I would definitely—I think we talked about this as well—a lot of these populations that now live in these places lived through a cartography that was left behind by the departing colonial forces. Modern international law, as we know today, was in some ways created to protect the colonial enterprise. That is still being employed today to deal with these negotiated settlements that were created. We have never given these groups of people their own opportunity to come up with their own imagined community, their own imagined political community.

Those are all important things that we have to deal with. I think those are all questions that relate, whether it's India, whether it's Iraq, whether it's South Sudan. I think this idea of giving people the right to imagine their own political community is important.

That's when ethics comes in as well, because it's not just a question of what; it's also a question of why. I think those would be the most important takings that we should take away.

LIANA STERLING: Of course, that feeds into what I'm prompted to think about in other parts of the world today, other geographic regions, where this pattern of contested borders, failed states, international intervention—there's a chain of events. Can you talk to that a little bit, what we're seeing in other parts of the world, how this project helps us think about that?

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: Of course. One of the things that we spoke about as well was the question of Iraq. Everybody is having these ideas about what and when and why. Often when that happens, a very good professor of mine once said, all this is historicized. For example, if you take the question of Iraq, let's go back to not the 1950s or 1960s, but let's go back all the way to 1920. You had Gertrude Bell and Percy Cox and T. E. Lawrence talking about the question, "Oh, what are we going to do with Iraq?" What, really, Gertrude Bell does is, she draws a line around Baghdad, Basra, and Mosul.

Then you have the Kurdish question. You look at the documents from the Cairo Conference. Some of the things that you talk about with the Kurds are things like, "Oh, we should keep South Kurdistan as a part of Iraq, because, who knows, maybe the Turks might attack." Then they say, "Oh, these Kurds, you cannot trust them."

Another thing that happens at this time is that the British Army does this indiscriminate bombing, one of the first aerial bombing raids that happens in Kurdistan. The justification given for that is, "Oh, these are uncivilized people, and it's completely okay to bomb them into submission."

What has always appalled me is that this language continues to play out today. We still have the same dialogue of "how do we deal with it," without giving the population, whether it's the Kurds, whether it's the Sunnis or the Shia or other minorities of Iraq, the right to imagine their own political community. It's always taking the people who matter the most from the equation. I think those are things that we really need to understand, and we need to go back to the very beginning to understand where these conversations begin and how we can actually engage with them in a much broader sense.

QuestionsQUESTION: My name is Shazia Rafi. I used to be the secretary-general of Parliamentarians for Global Action. Now I work with a consulting firm.

I really found this extremely interesting. My two questions: How did you actually get permission? I've dealt a lot with the governments of India and Pakistan, even on things that were less contentious, and these are very heavy bureaucracies to get permission to do what you want to do in terms of research.

And when it comes to the areas where houses, regions, particular families were divided, how have people dealt with this idea of citizenship?

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: Thanks for the second question. I really appreciate it.

On the first question, how does one get permission, I have an Indian passport, which means that it gives me access. Often I don't try—bureaucracy bothers me, and I like breaking rules. I shouldn't say it in public, but I do. The first time around, I just went. I went and I rented a car and I drove. If I had to go through the ministry in India and get permission for it, probably they wouldn't.

Also when I would go to these places, surprisingly, the border security guards—because a lot of the camps along the India-Bangladesh border are manned by the Indian Border Security Force—they always got to know I would turn up. I turned up in this place called Taki, which also happens to be the site of India's border pillar number zero. Within minutes, I had this very strapping young man turn up at the little hotel that I was staying in. They know. Other times I would just drive up the border security camp and say, "I'm doing this. It would be great if I could have a conversation with you."

They don't get visitors like me, so often people get very excited and they want to talk. They want to tell you things.

My mother is from this part of India called Andhra Pradesh. She speaks Telugu, and I speak Telugu as well. A lot of the Indian Border Security Forces follow the colonial rule, in which often you recruit people from different parts of India to serve. These are men and boys who serve in parts of the world where they have no physical geographical connection. So when I turned up in this part of the world, a lot of these young boys spoke Telegu, and they were just excited to see someone who spoke this language, because in that part of the world you speak Bengali, which is very different.

There were some times when I was denied. But you would always be surprised at the power of multiple visits to a place. And Old Monk always seem to help. It's a rum that they drink in India. It helps.

The second question is about identity and how people see themselves. I don't think they think in terms of citizenship. These are people on whom we have imposed a set of lines. For them, citizenship translates to an ID card, and ID card translates to an ability to move from point A to point B. Once you talk to them for extended periods of time, they will tell you, "Of course I cross illegally. I walk across the river and then there's Bangladesh. My grandmother lives there. I'm going to go see them."

Once, I remember, in Taki as well, a bunch of these very beautiful Bangladesh women dressed in their finest were walking across. This boy who was with me, who was kind of interpreting things to me, told me, "Oh, they just came from Bangladesh for an evening walk," which means that in a porous border, people circumvent these ideas of borders all the time. These are also places that are now getting fenced, which means that this is not going to happen all the time.

I have this photograph that I really like in which in front of India's border pillar are a bunch of boys from India and Bangladesh who play a game of cricket every single day. Anybody who is from South Asia realizes how contentious these cricket matches are.

I think citizenship is a construct that we hold onto so much. For many people, it makes no sense to them. It really doesn't.

QUESTION: My name is Bill McGowan. I'm a journalist and author. I actually wrote my first book about Sri Lanka, which I covered for two years in the late 1980s.

I'm looking forward to the final product of your work tremendously, because it's fascinating. I love the idea of sneaking across things.

I am curious. Why didn't you look at Tamil Nadu and its relationship to the Sri Lankan Tamil situation? That's part A). It seems, with your historical depth and acuity—it's not a land border, but in terms of Tamil irredentism, it's very much alive.

Number two, if any of your journeys, explorations, research can speak to what's happening in Burma with the Rohingya? I know India doesn't share a direct border with Rohingya areas of Burma, but it does share a border through Assam. Could you sort of assess what might happen vis-à-vis India's government with that situation?

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: In terms of India's border with Sri Lanka, I'm half Tamil, which means that the issue has always been—it's something I grew up with, growing up in India. I felt that India's relationship to Sri Lanka—there's a very small land border that actually connects Dhanushkodi. That's the point.

I felt that the idea of Sri Lanka is something that needed its own space. In terms of historical and geographic continuity, it felt like it was too much for me to handle.

It's also my own shortcomings. Sri Lanka and the Indian question is personal and it's political. I never felt that I had the maturity, at least at this point in time, to address it. This is not something where somebody funds me and says, "Why don't you go take a look at it?" A lot of my work that I do is not only political; it's also personal. And I felt that that was something that has to be left for a much larger question.

Today Sri Lanka is going through a transition in which many of the narratives of what it meant to be part of the civil war is changing. People who had to live through this terrible trauma are now trying to figure out how do they oppose their identities in order to be a part of a future Sri Lanka that is going to be quite indiscriminate with the Tamil population. That is still happening today.

I think the 20th of November is the Heroes Day. They celebrate the heroes of Sri Lanka, the martyrs. I think, if I'm not mistaken, the Sri Lankan state is now trying to stop the celebrations because they are still concerned about the former LTTE [Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam] members and what it might mean.

I don't think at this point in my life I have either the intellectual capacity or the maturity to tackle a subject like that. Also it's very personal. Perhaps in a few years' time, if I feel I'm ready for it, I would do it.

The question of Burma is incredibly important. I think while the border situation is not directly a border, what you really think about is that when you look at South Asia, it was a true melting point. A lot of these people who now live in the Arakan state traveled—the history goes back many, many years. It's not just a recent Bangladeshi migration. Some of the history goes back as early as Portuguese and Arab migration into the region.

My biggest concern is not just the question of human rights, but if you take away a people's history, that's the only way you can destroy them. You kill a bunch of people. You kill a bunch of boys. You deal with them. You put them in these camps. They will come back. But if you take away from a group of people their right to a story and their history, that is when you take away everything from them.

The problem with the Burmese state that I have is not just the question of human rights. It's also telling that these are new migrants who come here. They have been here for 30 years, 40 years. That for me is a much larger concern and question. Every few months you will find an op-ed in Al Jazeera, you will find an op-ed in The New York Times, but I also feel there have been very few people who have spent extended periods of time understanding these populations.

In relation to the Indian government, I have no idea. That's just not a question that I am equipped to answer.

QUESTIONER: Just a quick follow-up. With its sizable Muslim population, it's not an issue, the fate of upwards of 1 million Rohingya Muslims in Burma? At one point it was joined at the hip with India. As a matter of fact, you mentioned the diversity. It should be remembered that John Furnivall, who was a foremost British historian and civil servant in Burma, was the first one to coin the term "cultural pluralism" in 1932 in relation to the fact that there was no real border between British India and British Burma.

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: Of course it's important. It's important that we address these questions. It's paramount that we do it. But my answer is that I have no idea what the Indian state is doing. I don't speak for the Indian state. I don't think anyone can speak for the Indian state. There are people who can, I'm sure, speak to it. I speak only as somebody who is interested in these people. And of course it's important.

The problem with taking away a group of people and exiling them as if this land doesn't belong to them, this is appalling. Struggles with geography are something that nobody can leave. We all are tied to the struggles that our history and our land are connected to.

So I absolutely agree with you, it's of paramount importance. But I cannot speak as a voice of the Indian state. I refuse to speak as a voice of the Indian state.

QUESTION: I would love to hear a little bit more about what you think are the risks to the central governments of these porous borders. You spoke a little bit about some of the actions that are being taken in terms of building fences and so forth. Is this a concern to the government? What's being done to change how open these borders really are?

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: You're interested in what the governments of India and Bangladesh are doing?

QUESITON: Yes, especially the Indian government. I'd be curious if you did any research into what the perspective is there on both those regions, as well as any of the risks of the porousness of the borders and the lack of citizenship of the people that live around there.

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: To understand this, I think we have to go back to 9/11 and the global war on terror. I think that that fundamentally changed the way the Indian government, and to a large extent the Bangladeshi government, started looking at migration that they could not contain, or undocumented migration. The fencing became a part of this huge war against this terrorism that was considered to be a global war that we had to fight.

Since then the fencing has been in full swing. If you talk to the army commanders in these places, they are happy with the fence. They like the fence. They feel that this is how they are going to stop "the bad guys"—those are actually the words that they use—from coming in.

What also happens in this place is that over the last couple of years India has, if their numbers are to be believed, between 500,000 to a million undocumented Bangladeshis living who have crossed illegally into India. Often this becomes a political issue, it becomes an issue of security for the Indian state, and they have constantly been struggling with how to deal with it. With that also comes the idea of the sense of looking at Bangladeshis as "the Muslim other."

So these are all problems that the Indian state is facing.

But one thing that has happened over the last couple of years is that a lot of the Bangladeshis crossing it illegally have been shot at. If I am not mistaken, in 2011 I think, a 15-year-old girl called Felani Khatun was shot trying to cross back. Her family crossed in illegally many years ago, and then her father was taking her back to Bangladesh to have a marriage. The girl was shot while trying to cross the fence. It caused a bit of an uproar.

For the first time—I am not sure if it was a commander or a soldier—but the soldier was actually court-martialed. It never happens, but he was court-martialed in some sense and he was found to be not guilty.

Those are also things that the Indian state has to deal with, because the Bangladeshi government now is very concerned. The Bangladeshi government is just as bad. I am not saying that one is more bad than the other. They are all equally bad when it comes to protecting their citizens.

But those are things that have escalated. I think there has been an aggressive push to fence the entire border. India also sanctioned another 1,800-mile fencing along Arunachal Pradesh, which is the border of the contentious part with China.

QUESTION: My name's Michael.

You spoke about the need for more imagined communities along these contested spaces, and perhaps freedom to do that. I guess we can understand how fencing probably gets in the way of some of that imagination. Is there activity going on spontaneously within these border regions that you cross where there is that imagined community arising, out of the populace or where there are intellectuals, thinkers, artists that are trying to explore this space that you encountered?

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: This idea of the imagined community has always existed. What I spoke about was very specific to giving these people an opportunity to transform this imagined community into a political community that they can live with.

People do it every single day. They do it by living on these borders. They do it by playing cricket. They do it by crossing the border multiple times. So they do it all the time.

I think for many, many years, whether it's your war between Israel and Palestine, whether it's your Berlin Wall, whether it's your fencing, you have had a lot of artists who have worked on these issues. But for an artist to work on these issues and project them, say, in a gallery in New York or elsewhere is very different than the people who actually live there every single day.

It's not a no-man's land. These borderlands and these frontiers are very, very active. They are rich with everyday subversion. The real subversion happens by the very act of living. To give that act of living a more political dimension or a space for them to have that dimension is what we need to go towards. End of the day, as I said, our struggle with geography is always there. Edward Said said it, to borrow from him: Our struggle with geography never goes away—where we are from, what we are tied to. That land somehow is so important to so many of us. And it's very few of us who don't have that. How do we expect these people not to have a political view of this world when it's tied to their land?

For me, in that sense, I think some of the best work that came out came out through a lot of these Bangladeshi poets, this brilliant poetry that happens in all these places in which people are constantly talking about subversion. It has happened throughout South Asia's history, as many, many means.

I don't think I particularly know about other artists, but that's definitely a question. I'll go and Google it when I get home.

QUESTION: My name's Josh.

You talked about it being very personal. I imagine thinking about doing a border trip in America would probably have some very personal preconceived notions. I was just wondering if there was anything that came to mind through this journey that you have taken that has defied some preconceived notions that you maybe started out with that you would like to share, something that maybe changed your mind about something.

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: I will start with Afghanistan. I really thought Afghanistan was going to be exactly like Indiana Jones. When I was trying to embed with the army, I put my friends through a terrible time. I would work out in the morning and then I would not finish my coursework—and people like Josh actually helped me finish my coursework—and then I had to go lift weights. I was getting ready for an Indiana Jones kind of experience.

Then I go there, and what you realize is that it's completely different. That's one of the reasons why I took up this project. The world is being narrated to us, whether it's the policy world, whether it's journalism, whether it's television or media. So I also went with these preconceived notions of what the Afghanistan-Pakistan border would be. I was expecting Omar Sharif to turn up. That doesn't happen, but it's a part of our own orientalization, and that still exists.

What you realize is that people are a lot more complicated. They are not tropes. They are not caricatures of each other.

The first thing that I felt very humbled by was the everyday reality and the complexity these people live with—and yes, live so effortlessly. So that was one of my first preconceived notions that got completely taken away.

The second thing is that people take their politics very seriously. By politics, I don't mean Occupy Wall Street. I don't mean protests. I talk about the politics of just living in a certain way. That seems to happen a lot. Those are things that we fail to write about, think about. It's not traditionally interesting or sexy.

But what is really interesting is that acts of everyday resistance and accommodation happen hand in hand. Those were things that I felt completely humbled by. Often when I would sit down to write, I would have this deep existential crisis. I would cry, and my husband would be like, "It will be fine," and I'd say, "I don't think I can put to paper what I've seen because it's just so difficult to articulate it." But then, my job of articulation is insignificant as compared to people who live this life every single day.

So starting from Indiana Jones to my inability to write, I think it has been a pretty humbling experience.

QUESTION: My name is Lidia.

My question would be, if you had a machine to travel back in time to 1947, is there any key issue that you would address to maybe not avoid, but appease these conflicts? Or do you think these conflicts stem more from our Westphalian idea of a state and border definition?

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: Oh, wow. Time machine.

I don't know. I really don't know. But one of the things that I have come to realize is that often it's easy to act and then think. There's this poem by W. H. Auden. He's an Anglo-American poet. He writes about the partition. The poem is about Radcliffe, who was the man who was given the task of separating the nation. He had seven weeks and he had four judges, two of them Hindu, two Muslim. He had maps that were out of date. He had census figures that were out of date. In the poem, he says something about "he had to make peace between people with different gods and different diets."

I just kept thinking, did this man even know, whether it's Radcliffe or Auden, who were both writing about India? No, they didn't have different gods and different diets. They were very similar people. One of the things that they compromised was the rationality in that time. You don't split a continent that has had a cultural historic memory going back a few thousand years, over a period of seven weeks.

Having said that, if I go back to 1947, I don't think that would happen, I would actually have to perhaps go much before that. You would probably have to stop the partition of Bengal. You would probably have to stop the Morley-Minto Act. You have to go, not to 1947, but maybe a good 50 years before 1947 to perhaps see if all of this would be good.

But I would still go back to 1947, because my first crush was India's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. He was a very strapping man. He smoked, he spoke the Queen's English, he was an atheist, and he was quite the ladies' man. So I would definitely go back to 1947 just to see him. [Laughter] But otherwise I would definitely go back a good 50 years before then.

And if you know a time machine, I'm here.

ALEX WOODSON: I was just wondering if you could just give us an update on where you are in your journey, when you are going to be next going back to South Asia.

SUCHITRA VIJAYAN: If you look at the map, I've done the parts of Northeast and I've done Kashmir. I need to go back to Kashmir, and I definitely need to do the border with Rajasthan. The border with Rajasthan is something that I need to go back to.

I think I probably have another six months of research and understanding. Then hopefully, when I sit down to write, I will have, if not interesting, at least important things to say.

On that note, I actually came across this fascinating—there's this camp called the Deoli camp, in which during the 1962 war—India has a huge population of Indians of Chinese descent. Just like the United States of America, India has a grand tradition of interning its own people. They took away Indians of Chinese descent and they interned them. The majority of the Indian Chinese population lived in India's Northeast. They interned them and then moved them all the way to this camp called the Deoli camp in Rajasthan.

This is the first time I'll probably not trace the map. I'm really fascinated about this camp, and I've been trying to track down the Central Police Reserve officers who served, who are also Indians from a different part of India, guarding an internment camp in which Indians were kept for four years. There were men and women who were born and raised in these camps. Some of them were returned back to China, and they perished because, for all purposes, they spoke better Bengali than they ever would speak Mandarin. A lot of their properties were taken away, and the Indian government never quite acknowledged their existence or the fact that this internment camp happened.

Hopefully I'll get to do that soon, early next year, and hopefully, when I'm finished, I'll have something interesting to say. If not, I had a jolly good time.

LIANA STERLING: Suchitra, thank you so much for being with us tonight. And thank all of you for being here.