Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto's simple but revolutionary concept of the importance of property rights and rule of law is transforming developing countries around the world. He shows that by creating clear, enforceable, universally recognized property laws, they stand to realize $10 trillion in "dead capital."

Introduction by Joel Rosenthal

Welcome to the 21st Annual Hans Morgenthau Memorial Lecture on Ethics and Foreign Policy. This event is the highlight of the Carnegie Council's programming year. I am delighted that there are so many of you here to enjoy it.

The English critic Samuel Johnson said that great literature should serve two purposes: it should delight and instruct. We like to think of this lecture program in that vein, as an occasion to gather together to delight in good fellowship and to learn from our distinguished lecturer. This program also affords us the opportunity to recommit ourselves to addressing the most urgent moral problems of our time, and in doing so to honor the memory of Hans Morgenthau. Hans Morgenthau was not only an important figure in the life and development of the Carnegie Council; he was a central figure in the intellectual life of America and in the lives of all who care about ethics, politics, peace, and social justice.

In his recently-published biography of Professor Morgenthau, Christoph Frei explains that when Hans Morgenthau fled from Europe in 1937, an unrecognized young scholar with few worldly possessions and few useful connections, he came to America as a frustrated idealist. "For Morgenthau," Frei writes, "the world was not a friendly place. In his native Germany he had no professional prospects as the Nazis rose to power. He went on to Switzerland, then to Spain, Italy, and France. At the end of his odyssey, he arrived in the United States, where he was forced to begin completely anew."

Begin anew he did, overcoming hardship to land a professorship at the University of Chicago, where he taught and wrote his master work Politics among Nations, first published in 1948. In Politics among Nations and other writings, Professor Morgenthau warned of the hazards of moral crusading, the self-righteous moralizing that characterizes the rhetoric of so much foreign policy; and of the dangers of its opposite, cynical amoralism, where politics is seen as nothing more than an arena where the strong do what they will and the weak do what they must. The objective was to find a middle ground, a place where moral clarity and moral commitment could be acted upon without becoming either counterproductive or insignificant. Professor Morgenthau's realism, known so well for its emphasis on power and interests, was a moral concept at its very essence. It was the realism of an idealist who had seen the worst of human experience.

Our speaker this evening understands this view of the world. He begins with the insights and experiences of a realist and the aspirations of an idealist. If I may quote from last year's New York Times Magazine profile of him by way of introduction:

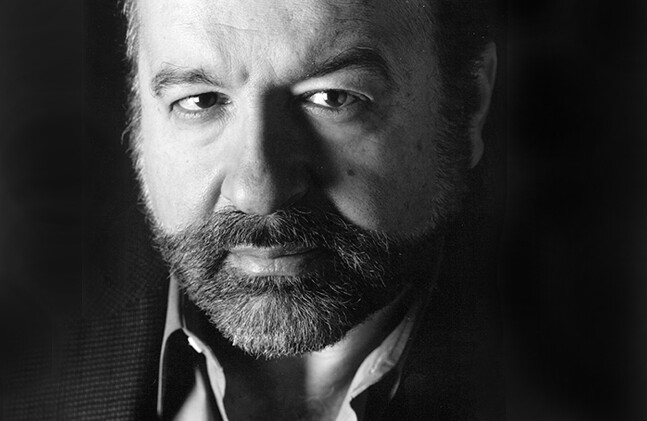

Hernando de Soto didn't start out planning to save the world. Born in southern Peru, he left early, after his father, a diplomat, took a post abroad, eventually ending up in Geneva. Returning to Peru, he was deeply struck by the overwhelming poverty. The gulf between Europe and his homeland was inexplicable, he thought, when the quality of the people was the same. After returning to Switzerland for his master's degree, Hernando de Soto went to work for the GATT. By age thirty, he was chief executive of an engineering firm with worldwide business reach. In 1983, Hernando de Soto founded the Institute for Liberty and Democracy (ILD), headquartered in Lima, Peru, whose purpose was to study the informal economy of Peru and to push for reforms to help the poor. The Economist magazine has deemed the ILD as one of the two most important think tanks in the world, and the German magazine Entwicklung und Zusammenarbeit [Development and Cooperation] has called Mr. de Soto one of the most important development theoreticians of the last millennium.

Hernando de Soto is the author of two major books on economic and political development: The Other Path, published in 1986, and The Mystery of Capital, published in the year 2000. A thinker, a doer, an adviser to world leaders, Hernando de Soto has shown great vision, creativity, persistence, and personal courage in his quest for social justice. We are fortunate to have him as our 21st Annual Morgenthau Memorial Lecturer.

THE MYSTERY OF CAPITAL

Thank you. I am delighted to be here. Professor Morgenthau taught me in Switzerland many years ago, when I studied at the Graduate School of International Studies. I thought at that time that I would be a theoretician. But then I went on to spend my life in business, doing practical things. Occasionally, however, the temptation has come to synthesize what I have learned from everyday life.

My primary interest is in development. I come from a developing country, and I am extremely concerned with why we do not make it. Talking with my friend, Francis Fukuyama, the other day, I asked him, "What separates the 5 billion people in the developing world from the 1 billion people who have made it?" His reply was, "Of course, trust. People in developed countries have a network of trust. They trust each other."

A recent statistical survey carried out in many countries asked citizens: Do you trust the people that you meet? As it turns out, 60 percent of Scandinavians trust each other; about 45-50 percent of North Americans trust each other; but only 7 percent of Brazilians trust each other and 5 percent of Peruvians. I was very depressed about this, but then was able to cheer myself up remembering that I would soon be traveling to the United States, where most people trust each other.

Until, that is, I went through immigration in Miami. The immigration official said, "Would you please identify yourself?" I said, " I'd be delighted to. My name is Hernando de Soto. I am the son of Alberto de Soto of Arequipa and Rosa Polar Moquegua; and they have two children." He said, "Would you mind just showing me your passport?" Which I did, as I realized that he did not trust me about my identity, but what he did trust was my passport. I said, "Interesting. I thought my identity was with me, but obviously it is not associated with my physical presence; it has been transferred to and is represented in a uniform and standardized written document, which provides information and is based on rules that allow me to travel globally."

Then I came here to my hotel where I have been staying for about fifteen years.

"It's good to see you again, Mr. de Soto."

I said, "Great to see you as well, Herb."

"Tell me how you will be paying."

I said, "Promptly, as usual."

But then his next question was, "Mr. de Soto, will you please show me your credit card?"

Here is a man I have known for fifteen years, he is a member of one of the New York tribes that I am familiar with, and he still does not really trust me. At that point I realized that neither the commercial credibility nor the track record I had established at the hotel was valid. What made me financially credible was the representation of my status in a plastic card, allowing me to prove to anyone around the globe that I pay my debts.

That reminded me of Immanuel Kant, who said that people only know about other things through representations; nobody really knows anything directly. Both of these Americans that I had met in just a few hours were able to trust me through two forms of representation—passports and credit cards—that your society has, while mine does not.

By now you may have noticed that I came in with an apple. I hope you understand that this is my apple. I've got various witnesses to prove that this is my apple. But no matter where I look on this apple, there is nothing on it or in it that shows it is mine. Nowhere does it say, "This is Hernando's apple," or "This is Mr. de Soto's apple." It doesn't tell you whether I can transfer it, pledge it, lend it, deposit it as a guarantee, use it as collateral, nor does it say whether I can export it, import it, or cut it up into segments and divide among partners.

What that means, therefore, is that property, like my identification or my reputation, is essentially a man-made construct. It has nothing to do with the physical world. The documents I have mentioned indicate whether we can be trusted, whether we can be identified, and whether our possessions belong to us and what we can do with them and how we can leverage them. In other words, all of the elements that make market economies work are not really physical things; they are constructs about physical things. There would seem to be two worlds: the world of apples, of physical things; and the world of manmade constructs, of representations, which come through law and which allow us to communicate among ourselves about physical things—myself and the apple.

When someone goes to the Chicago Mercantile Exchange to sell 10,000 head of cattle, he doesn't drive the cattle into the building. He brings along documents proving he owns the 10,000 head of cattle, and these documents tell you things you could not see if you looked each cow in the eye.

If you go to the London Metal Exchange, people are trading nonferrous metals, but nowhere does a forklift take bars of gold from one side of the room to the other when somebody trades. Rather, the traders move paper that represents these bars in the form of property. Transactions take place by transferring property rights to these bars; and such rights are concretized on legal paper or computer blips. The only assets that can efficiently travel locally—or internationally in the global economic system—are those legally represented on paper, subject to rules that enforce property rights. The foundation of the economy, of capital, is property law.

This point was made some time ago by both Adam Smith and Karl Marx. They both said that the most important thing you could have in economics was capital. Whether or not they knew they were living during the Industrial Revolution, they could see that something was happening whereby one could draw from objects and from human actions a variety of things to create wealth that would not have otherwise been possible. Capital, they said, is what makes the world go around and what makes economics function.

Tellingly, the word "capital" comes from the Latin word capita, meaning "head." It appears to have originally stood for "head of cattle" or other livestock. Livestock have always been important sources of wealth beyond the basic meat, milk, hides, wool, and fuel they provide. Livestock can also reproduce themselves. Thus the term "capital" begins to do two jobs simultaneously—capturing the physical dimensions of assets (livestock) as well as their potential to generate surplus value.

First Smith and then Marx were very explicit that capital is not money; capital is a value that is very difficult to capture. Marx even called capital the "hen that lays the golden eggs." Without it, the economy would not function; and it was worthwhile to get normal people to control capital, because otherwise it would be controlled by an exclusive minority that could exploit the world.

Likewise, Smith said that capital meant the accumulation of physical wealth—but could only promote growth provided it was appropriately fixed. What did he mean by "fixed"? Nobody who dealt in the worlds of politics, economics, and law ever thought about the world as only physical things—apples. They always thought about objects with their metaphysical attributes.

Thus, when Adam Smith talked about fixing the value of things, he meant fixing as property, which meant attaching that property to a legal document—just as my identity is fixed in my passport and my capacity to pay, in my credit card.

For Smith, economic specialization—the division of labor and the subsequent exchange of products in the market—was the source of increasing productivity and therefore "the wealth of nations." Smith said that if products are not fixed, they remain dead; they have no life for the world of economics. One of the examples he gave was of the pin factory, where, if you couldn't divide the tasks involved in making a pin among the workers, productivity would suffer. What made this specialization and exchange possible was capital, which Smith defined as the stock of assets accumulated for productive purposes. Entrepreneurs could use their accumulated resources to support specialized enterprises until they could exchange their products for other items that were needed. The more capital that was accumulated, the more specialization could occur, and the greater the society's productivity.

Privatizing the Compañia Peruana de Teléfonos

Around 1990, Peru decided to go down the path established by the Washington Consensus. This meant that we would:

- stabilize our currency;

- promote fiscal stability; and

- unburden the state from its management functions—in other words, privatize everything that belonged to the state.

Some of the young researchers in my institute were invited to serve on the legal team given the job of privatizing the Peruvian telephone company, the Compañia Peruana de Teléfonos. Though run by government, the company was in fact owned by the people who used the telephones; their shares, in the Lima Stock Exchange, were valued at $53 million. But as soon as we tried to sell the company, nobody would buy it. The legal team went all the way to New York to talk to AT&T and BellSouth—but neither company would hear of it. Likewise, France Télécom wouldn't so much as consider it. Why? Because the company wasn't properly titled— it wasn't correctly represented.

For the privatization process to succeed, we had to re-title the Peruvian telephone company. In other words, we had to give it a passport that allowed it to travel and to spell out the law for settling any conflicts over the company's ownership with the private sector or the national government. Peru spent $18 million simply on redefining the Peruvian telephone company in such a way that people in New York, Paris, London, and Shanghai could look at it and say, "Ah, I recognize what I'm buying, what my rights are."

In 1993, once the title was clear, the team went abroad again, held an auction, and the company was bought by the Telefónica of Spain for $2 billion. $2 billion is thirty-seven times the value of $53 million, which as you may recall was what the company was worth when we first began the privatization process.

We didn't paint the company, we didn't repair the broken windows, we didn't touch any physical parts. We just refigured its passport. We touched the way it was defined by law such that interested parties throughout the world could concentrate on the value of the company and understand it in similar terms.

In essence, we had created capital. The difference between the $53 million and the $2 billion had nothing to do with the apple. All we did was change the property law and standardize it in terms that the global market could understand so that the title could travel around the world accomplishing multiple functions. We connected it with the larger market, with the larger global division of labor, making it easier for people to identify the company, assess its value, settle disputes over its ownership, and issue shares and bonds against its worth.

This is what happens when things are inserted into the world of law. People can then recognize them and see a value that would not otherwise be obvious, just like the man who received me in immigration and the man who knows me so well after so many years in my New York hotel but needs the identification that comes through law and through a card that is an acceptable device for transferring value. The capitalist system relies on rules and symbols.

Some nations do not have the capacity through their legal systems to represent economic value in such a manner that it

- can increase the information about the commodity in question;

- has mobility—I can travel all over the world with my credit card; and

- can be seen as fungible—meaning it can be split into different parts or have various functions attributed to it.

What allows the apple to act as collateral is not something intrinsic within the apple itself but the law assigning it a particular function.

This means that the capitalist system is a system of representations, which when working correctly, converts—as Adam Smith would have said—dead into live capital. When it doesn't go smoothly, these things have a much smaller value than otherwise. Returning to the issue of underdevelopment, the question now becomes: Do developing countries suffer from the problem that most of their assets are unrepresented? That is to say, their assets have no passports, no credit cards, thus no way of being symbolized and of traveling in the larger market.

Imagine yourself walking down a street in New York City. You see parks, land, and buildings. Now think of going down a street in Mexico City. You also see parks, land, and buildings. But how much of what surrounds you in each of these cities is live capital?

When President Fox asked for my institute's advice, we gave him a list of one hundred things a building does in New York that it does not do in Mexico. When you are in Mexico, buildings give you shelter and allow you to work and live in them. But buildings in New York further allow you to mortgage and rent them, and to have an address where you can collect electricity or water bills. When it has all of these other functions assigned to it by law, an asset becomes live capital, as Adam Smith would have said; when it does not, it is dead capital.

My institute assists heads of state all around the world with investigating how much dead capital their countries have. To what extent are the nation's assets and the work of its people represented in legal documents? To what extent are these assets and labor governed by rules that allow them to act as collateral, fetch credit, and encourage the owners of goods to issue shares against which a nation can foster investment? We investigate the country's law books and find out how many of its buildings are titled; how many of its cows are represented in such a way that you don't have to drive them to the mercantile exchange.

Cairo's Tilting Buildings

When the Egyptian government called on my institute for advice, he said, " We've seen what you've been doing in Peru. We can relate to that because we have a large informal sector and black market. We understand that your way of classifying dead capital versus live capital, where the law is and it isn't. So can you come talk to us about it?"

I said, "Yes, but we'd like to talk to you in Egyptian terms so that we are quite clear about what we are conversing, because if I give you just Peruvian figures and maps, you will say, 'Oh, these poor Peruvians. I'm sure that it's bad in Egypt, but probably not that bad.' So we have to talk about Egypt."

After a year-long project involving some six Peruvians and fifty Egyptians, my institute presented a four-volume report to the Egyptian cabinet. Nobody was going to read four volumes, so we also gave them one sheet of paper with five pictures. (If you can't sell your argument to a politician in ten minutes, you can't do it.)

The first picture we showed them was a map of Cairo. One minister said, "I recognize the map and I recognize that it is Cairo because of the way the Nile twists and turns. But what I don't recognize is the color coding."

We had used nine different colors to identify the way real estate assets are held in Cairo. We had discovered that as in Peru, most Egyptians work outside the law. It doesn't mean these people have no law. Rather, they have rules that they themselves have created—similar to what Americans did during the 19th century. In the United States of 150 years ago, fines for disobeying the law were very different from village to village; the sheriff basically established what the fine was. California, for instance, had 800 types of rules in the mid-1880s, known as the Mining Claims Association.

What America experienced then is similar to the Cairo of today. Cairo residents have nine different ways of holding assets that are determined not by the government but by the people's own law. We told President Mubarak that the gold band on the map represented buildings that have been built on agricultural land, and thus are extralegal. To which one of the cabinet members responded, "But that's not only extralegal, that's unconstitutional, because our national constitution clearly establishes that you can build only on desert land. We've got little agricultural land and only one river to irrigate it. That's a crime."

I said, "It's outrageous. We can't have that. However, my team has used photogrammetry to measure the number of buildings on agricultural land, of which there are 4.7 million. At $10,500 per building, established by a surveyor that your government trusts and respects, I calculate that you've got about $50 billion of dead capital in just the agricultural sector."

I told him that one of the other colors indicated buildings erected on cemeteries and that the color in the center indicated public housing. The Minister of Housing immediately recognized this. He said, "The government built that housing in the center of your map, so how can it be extralegal?"

I said, "Yes, I'm sure that you built them legally, but as you may recall, these buildings are in Nasser City, where you only allowed two-story buildings. These are six stories. So you need to ask: Who built the other four stories? Obviously, it was the people who lived in story number one and in story number two. They made a deal and built stories number three, four, five, and six; I could show you other places where they even went up to ten. You can see that in the Cairo horizon, where some of the buildings tilt slightly to one side or the other."

All of a sudden, our Egyptian friend started realizing, as we had in Peru, that a large part of the enterprise in his country was functioning outside the law right under his own nose, but until now he didn't have the categories with which to distinguish one extralegal enterprise from another.

So what is the value of all the buildings that are owned extralegally, especially by the poor, in Egypt? The reply is $241 billion. What percentage of Egyptians own real estate outside the law? The reply is 92 percent. What proportion of Egyptian enterprises provide extralegal employment? It's 88 percent. Roughly 90 percent of all Egyptians live outside the legal system.

How much is $241 billion? It's fifty-five times bigger than all foreign direct investment in Egypt over the last 200 years, including the Suez Canal and the Aswan Dam, thirty times greater than the market value of all the companies recorded on the Cairo Stock Exchange, and roughly sixty-eight times the value of all foreign and bilateral aid received by Egypt, including World Bank loans. In other words, the group in Egypt with the largest accumulation of assets that could be converted into capital are the poor, but they're not inside the legal system, they don't have "passports," and you can't create a market economy out of them until they are governed by the rule of law.

Why does Egypt have so much illegality? Maybe there is something behind the Samuel Huntington "clash of civilizations" theory that people who are not as pink and as Protestant as others are less capable of generating wealth.. We Latin Americans have been thinking about this, wondering if Professor Huntington may be right. But before we consider his theory, let's look at the obstacles to obtaining property in Egypt by legal means. My institute examined Egyptian legal precedents to see how long it normally takes someone in Egypt to build on a sand dune outside agricultural land. According to our findings, they need to do seventy-seven contracts with government, which means visiting thirty-two government offices—a process that usually takes about seventeen years.

By this time my Egyptian friends were getting depressed. I said, "Don't get depressed. When we first got started in Peru, the process of buying land legally took twenty-one years. And when we got depressed about this figure, we said to ourselves, 'Don't be so depressed. In the Philippines it's about twenty-five years.'"

As mentioned earlier, we recently finished a study with President Fox to begin a large project to redesign the property system in Mexico. The number of Mexicans living outside the law constitutes 78 percent of the total population—less than in Egypt, but still substantial. Mexicans hold extralegal assets of appproximately $315 billion, which is seven times the size of the country's total oil reserves, or twenty-nine times the size of its foreign direct investment.

Thus in Mexico you get the same picture as you do in Egypt and Peru—I suspect you would also get it in Russia or Montenegro. The industrial revolution has begun, but the instruments that allow capital to travel and the market to function are simply not in place. When we do the sum total of what we believe are the assets held in dead capital throughout the developing world—including the former Soviet Union—it comes to about $10 trillion.

What seems to have happened in places like the United States and Western Europe is "exaptation." It's a word—the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins uses it to describe the evolution of language—indicating that species sometimes invent things for one purpose, and then it evolves a second purpose. Birds developed feathers for insulation, but then feathers also helped them to fly.

Let's see what happens when we apply this principle to Western definitions of ownership, During the 18th and 19th centuries, the West defined its property system. Originally, that system was developed to protect ownership, but through representation it became the process that produces capital; the same process that Adam Smith and Karl Marx were talking about.

The industrial revolution has now arrived in developing countries. Port-au-Prince in Haiti has grown seventeen times in the last thirty-five years. Lima has grown seven times. Guayaquil in Ecuador has grown eleven times. All over the world, from Egypt to the Philippines to Lima, there have been large migrations in the last forty years, and many of the people one used to know about only through the Discovery Channel or National Geographic have now, like Oliver Twist, advanced from presenting themselves at the desk of charity run by the First Lady of the country to introducing themselves to the head of state as budding entrepreneurs. You can't walk half a block in Cairo without somebody trying to make at least three deals with you. These people are all entrepreneurs, yet they don't have the law on their side.

And just as advanced countries once learned that they had to change the law to give the poor property rights—that was the only way to harness the growing tide of energy from a new society that was sprouting up spontaneously in response to the Industrial Revolution—the developing world, too, needs to adapt its laws to give the vast majority of people the property they require to participate in the standardized global economy on an equal basis.

Lessons from Germany and Switzerland

As mentioned already, part of the answer could be cultural. Some cultures are capable of creating, over time, a functioning legal system, whereas others are not. But in that case, the only way the legal system could develop would be spontaneously. According to the findings of my institute, that is not the case. We combed through the history books to see, for example, how Germany got its property system. It came as a result of war. A law protecting property was created after Germany was defeated by Napoleon in 1807. Having tried unsuccessfully to recruit troops, the Kaiser was looking for ways to recruit people and came up with the idea of offering them property titles as a way of increasing the pool of those eligible for military service.

Five hundred years had passed since the Bauernkrieges, or European peasant wars, had begun, with the goal of toppling the feudal system and giving property to ordinary people—Martin Luther joined the struggle in 1520 with his writings condemning the tyranny and greed of the pope and his cardinals. By the early 19th century, the German bourgeoisie could no longer resist the peasants' demands. The Stein-Hardenberg reforms were introduced in 1833, enabling peasants to purchase the land they occupied by paying in installments. This increased the pool of Germans who could go to war. The Prussians finally defeated Napoleon in 1870—and in the process got a property system.

Something similar happened with the Swiss. At the end of the 19th century, Switzerland was one of the poorest countries of Western Europe; but then the Swiss decided, when they saw their prosperous German neighbors, to reform their property system. At that time, Switzerland was so poor that even travel agencies were regulated under the newly-drawn up Swiss Federal Constitution. This was not because the Swiss were traveling with phony pesos to Cancun but because they were being exported as cheap labor to Latin America and as cannon fodder to Southern Europe.

Prodded by the Swiss Federal Council, the Swiss entrusted a civil lawyer, Eugen Hubert, to find out how many of their citizens lived outside the law so that they could live within the law by possessing their own property. After twenty years of study, Hubert concluded that the Swiss actually had 179 different forms of holding assets. It took another twenty years before the Swiss found a way of bringing these assets under one code—the Civil Code of 1908—and creating a solid Swiss property system. This still survives today.

But to us Latin Americans, the discovery of what the Americans and Europeans had done throughout the 19th century, how they had organized their property, would mean talking to dead Europeans and Americans, where there's not much of a dialogue. And so we said: Isn't there somebody who is still alive whom we can talk to about this?

The Japanese Experience

We decided to talk to the Japanese. Until 1945, Japan was, economically speaking, organized like a feudal country. Under the occupation of General MacArthur, this changed. How? How do you take a system where only a few people have access to the law and make sure that everybody has the same rights? Where is the key to the lock?

We first perused the American history books, where we found some insinuations, as well as some data, but not the details of what we needed to know. We looked at the Japanese books, but they were just too technical. Ultimately, we managed to get some funds from a European foundation to locate the Japanese who had executed the transformation—seven surviving octogenarians who had overseen the process. We invited them to the International House of Japan, and we Peruvians came over and said: "We're starting to title Peru. We get all of our information from the bottom up. We find that there is a large informal extralegal sector supporting various rules of law, and what we aim to do is bring all of these rules together under a single legal system, one that meets international standards. Have you found a shortcut?"

Within two weeks, we had our answers. In fact, the Japanese had not used a shortcut. Our Japanese guests showed us a poster from 1946, when the government was announcing to the population that Japan was about to become a property economy. The problem is, the poster explained, that the government doesn't know how property or assets are held.

The feudal system had a mechanism whereby the lords collected taxes and rents from people, but what the Tanakas and the Sugiharas did with their assets was not the government's business. Ordinary citizens traded amongst themselves—bought, sold, redivided, and organized their assets. The feudal class wasn't very well informed of what assets the Tanakas or the Sugiharas held and in what form. And as long as this didn't threaten the social order, no one seemed to mind very much.

By the time General MacArthur arrived, Japan had a thriving informal sector. The basic organizational units were groups of local residents that kept records of their members' landholdings and other assets. At the end of World War II, there were 10,900 such organizations, indicating which parcels of land, buildings and businesses each family in a particular neighborhood owned. In most of their ledger books, you see pictures of individual Japanese sitting or standing on a plot of land with a sign saying, "I am Mr. Fujimoto; I own this."

Under MacArthur, the decision was taken to create a property system for Japan from the bottom up. The aforementioned neighborhood organizations were officially recognized as land commissions and authorized to transmit information on the holdings of the Tanakas and the Sugiharas to the prefectural authorities. They told the prefectures who owned what and how that property should be determined. The prefectures then reported to the Japanese government, which faced the task of codifying, professionalizing, and systematizing the law.

In essence, these legal reforms constituted an anti-poverty program. Poor people—of which there were many in Japan after World War II—were able to procure titles to their homes and businesses. The upshot was a market economy that nearly all of the Japanese could participate in.

Our Japanese friends showed us another poster from that time that tells the bare bones of this story in a series of three illustrations. During the Meiji Restoration, Japan imported mostly German as well as some French law to consolidate the property rights of the Japanese ruling class. This law was torn up eventually, as we see inside the first circle. Inside the second circle, we see farmers and neighborhood organizations reporting on their local rules to the government. The third circle shows the new law of Japan, which still stands today. This was all done by legalizing the informal law, the law that came from the bottom, with the active participation of Japanese people themselves.

No Law, No Capitalism

Why is all of this important? Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Russians, the Peruvians, the Egyptians, the Filipinos, and the Mexicans have decided that we're going for capitalism. Yet none of the standard macroeconomic recipes helped to create the rule of law.

When you look at the generous bilateral assistance the United States gives to our countries, there is very little—if any—requirement for a rule of law. Same for the World Bank, which sees the rule of law as a country's own internal matter. Yet capitalism can only take place where you are able to get a rule that allows you to form capital, because capital can't be picked up except through a legal document. You can't issue credit without the rule of law.

I don't know if you remember Donald Duck's billionaire uncle, who dives into a big swimming pool full of bills and coins. In my organization, the Instituto Libertad y Democracia, we speak of the "Scrooge McDuck syndrome" to describe the mentality that says that the world of money is distinct from the world of apples, when this is simply not the case.

As you may know, banking got started in Holland over 400-500 years ago. Chambers of commerce issued property titles on goods, which bankers were then able to use as collateral for issuing credit. Property came first, money second.

We Latin Americans have the highest inflation rates in the world, so obviously money isn't the problem. The problem is property and the rule of law—that is where capitalism begins. In most developing countries, there is no property. In essence, property provides the rules and symbols of orderly development. It also gives you the possibility of enforcing the law peacefully.

You had a dramatic event less than a year ago here in New York, but three days after 9/11 you were able to find out where thirteen of the terrorists had been because, thanks to your property system, you had the paper trails necessary to trace their movements. But you still haven't gotten Osama bin Laden because he lives in a country without property trails.

Some of you may remember the popular 1980s television series Miami Vice. It's about two very good-looking American cops who are trying to get a bad Colombian or Peruvian, someone who looks very much like myself. At the start of a typical episode, they talk to a beautiful blonde and ask, "Where is that cad Hernando?" She says, "That Hernando, he is no longer here. He has gone to 353 Stewart Street." So they get in their red convertible and go to 353 Stewart Street, where this beautiful brunette comes out and says, "Hernando, that rat, he is not here anymore; he's at 101 Ocean Drive." They get back in their red convertible and go off to 101 Ocean Drive. About forty-five minutes later, they catch the poor Peruvian. They have succeeded at what the New York police call "skip tracing"—using property information to get the man in question without killing too many people around him (just one or two!).

The property system allows you not only to create capitalism, capture value, and settle property rights; it is the basis for order. Likewise in international relations or relations with indigenous peoples, property gives you the tools to settle disputes peacefully.

Since the Carnegie Council is interested in international affairs, I imagine that many in today's audience have heard of Alsace Lorraine, the piece of land between Germany and France that has continually gone back and forth from Germany to France, from France to Germany. But the reason it's not so contentious—unlike what happens in border disputes within the Middle East or Latin America—is that it doesn't matter which nation has sovereignty. Monsieur Dupont gets to keep his property and Herr Schmidt to keep his. Property ownership depends on who made the original deal. It is much more solid than sovereignty.

We are all brothers and sisters in this world, but there are too many of us to be able to recognize each other by face. We need the rule of law, the system of passports. My book, The Mystery of Capital, describes how Americans of about 150 years ago came to develop a formula for the rule of law. This gave your nation the means for people to live peacefully and to generate wealth. Now the developing world needs to do the same. Globalization requires us to think about world order, but there can be no order without the rule of law. Then—and only then—can we have true global justice.

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

Q I'm wondering about how property gets transferred to poor people in Peru or Egypt: From whom it was transferred, and why did they allow the transfer to take place peacefully?

A Let's take the example of Haiti, the poorest country in the Western hemisphere. Haiti occupies the Western half of the island of Hispaniola, next to the Dominican Republic. My institute had a contract with President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to advise on how to convert dead into live capital. To do that, we had to walk the shantytowns. There was no problem about defining what was illegal and what was poor. It was all clearly visible.

We didn't find one shack in all of Haiti that doesn't have a property title; but not a single one of these titles had been issued by government. What that means is that while their government attended to other issues, Haitians went ahead with forming their own laws and settling their financial affairs. Somebody could of course come back and say, "Wait a second. When there was a French colony, all of that belonged to my family, Les Duponts." But possession is nine-tenths of the law, and it's obvious that Haitians have been able to organize the territory and represent their apples in a way that most everybody in the neighborhood accepts.

Let's take a more complicated case, that of Cairo. About forty-fifty years ago, President Nasser established a policy of rent control. But once there was rent control, tenants created their own legal system to sell, buy, or rent their apartments outside the law, and to ensure property inheritance. And this practice, though widely established, has nothing to do with the official law that says that the friends of Mr. Farouk who rented the apartment fifty years ago are still the tenants, paying rent of just $1.00 a month.

It's quite clear that the poor have already taken over much of the property in the developing world. Yet you will get into trouble if you go down the paper trail to another generation and a generation past that. To institute the rule of law, you must go to the people who currently have a system, and once you are able to identify it, bring that system into a common legal framework. At the same time, you have to strike a deal to clear the books. This is a political decision that can be accomplished relatively easily.

Q Do you have any broad-spectrum analysis showing that some developing countries work very differently from others—for instance, because of having been colonized?

A To be honest, I find it remarkable how similar most developing countries are today—with their massive informal sectors—rather than how different they necessarily were in the past. Indonesia, for instance, developed under Dutch law, but when you go into Indonesia today, 92 percent of the country is outside the law.

My previous book, The Other Path, talked about the informal sector in Peru. It was translated into Bahasa Indonesian. When visiting Bali some time ago, I got a call from the Suharto government through U.S. Ambassador Monjo, a friend of mine. President Suharto and his cabinet said, "This is very interesting. Peru seems to resemble what we have here in Indonesia. Can Mr. De Soto come and visit?"

I sat down with them, and they said, "Don't give us all of this stuff about why property is important. We know that. 92 percent of the country is not titled. We just don't know who runs the factories, who runs the businesses, who owns the land. That is our main problem. Tell us how we can find out who owns what."

So I said, "Here is what you have to think of. I have just been to Bali. It's a beautiful place. We walked from one rice paddy to another, crossing wonderful terraces surrounded by palm trees, showing rice crops at different stages of maturity. But we knew every time we were changing property because a different dog would bark. So what you have to do is listen to Indonesian dogs: they've got the whole story."

Whether we're in Indonesia, Egypt, or Peru, it's no different.

Q The rights of the individual are quite inbred in the American way of life, so that when one speaks of law, one is always conscious of individual rights. Now, with your system, individual rights have to be protected somehow. It comes back to the "barking dogs." But can developing countries achieve this?

A There may have been factors present in the United States that engendered growth in this direction, which simply aren't present in some of the countries I've mentioned. Start reading what Thomas Jefferson had to say over 200 years ago. It's completely different from what Peruvian people were writing then. You had better forefathers than we did!

From my understanding of U.S. history, when you began your conquest of the West, your common law system regarding property rights collapsed to the point where Congress had to pass thirty-seven preemption acts that said: "The common law no longer prevails. By statute, the people of California shall have this; by statute, the people of Little Miami River shall have that; by statute, the people of Kansas shall have that." This was because your law couldn't keep up with the reality of property ownership.

In Peru we have found that, on average, every parcel of land has twenty-one titles. In other words, the Peruvian government tried to determine property rights twenty-one times, whenever there was a peasant revolt. We did try your methods, but we had less success.

Rather than look to the past, it is much more interesting to start "listening to the dogs"—talking to people—about what they are willing to accept today. This puts us much closer to the truth than if we just looked at the past. For instance, let's say I'm allowed to operate a bakery in Cairo. How much time does it take me to get authorization to operate my bakery legally? It takes 549 days, working eight hours a day. How long does it take me to transfer a property title in Peru, if I live in the area of Ayachucho? It takes three years and six months.

Most Latin American countries are like Peru. In Peru about 30,000 rules are being made per year—or about 106 per working day. With that flood of rules, you can put rights in, but you can also take rights out.

Our congresspeople are not like yours, elected by district and, therefore, accountable to District Number 32 in New Jersey or District Number 3 or 4 in New York. We are elected by lists and we are accountable a la nación—ergo, to no one whatsoever.

So yes, there is something in your tradition that has made it much easier to create a property rights system that is sensitive to poor people.

Q What steps can be taken in certain countries like Argentina, where law and capital are ersatz, and corruption is essential?

A About three months ago, a friend of mine in New York asked me, "How exactly do you get your information?" I told him that in developing countries like mine, the informal sector is where you buy, it's where you sell, it's where you do everything." In every developing country, we talk to that informal sector. We have a very orderly way of going about this. First, we locate the most representative elements. Then we find out how they see the law, how they make their deals. This enables us to recommend corrective measures.

One of the last interviews I had in the Middle East was with a member of the informal sector—as usual, I was talking to the people so that we could make maps showing who is running what business and in which part of town. Anyway, we had finished our questionnaire and were getting along very well, so I decided to seek his views on corruption. I said, "Sir, could you tell me what you think of baksheesh, paying off people?"

The reply was "Baksheesh? Oh, I love baksheesh."

I said, "Tell me, why do you love baksheesh?"

He said, "If I have to deal with the law of my country—about a hundred things coming at you every day—life is not very predictable. But if I pay off five key policemen, who are poor, I am helping them and I can get something done. I could also pay off a judge, but I don't recommend judges; they're shifty, they're unreliable, and they're expensive. With baksheesh I've got predictability."

So when governments ask us, "What is the challenge we face when trying to create a new law that helps poor people?", my reply is, "It's got to be more predictable and accessible than the current official law because if it's not, the extralegal system will win out. People are reasonable, they are rational, and they will become squatters if it takes twenty-one years to get a sand dune legally."

The way to form the new law is to make sure that it is cost-efficient, for which you have many mechanisms in the United States that are not written into the Argentine constitution. We Latin Americans are very good at writing constitutions that look like yours but aren't the same thing.

When we bring out a new rule, there is no Office of Management and Budget that looks at it from a cost-benefit perspective. There are no "comment-and-notice" periods giving people the opportunity to comment on the first draft. There are no congressmen elected by districts that consult with their constituents. There are no sunset procedures.

Japan looks like a bureaucraticized system, but when you go there, you find out that when the Diet wants to make a law, it passes it to the bureaucracy, and the bureaucrats then bring together a consultative group, or shingikai, composed of all the key elements of society. The shingikai debates the law over a year or two. These debates are supervised by a press club, which is given office facilities for the purpose.

Once the law is drafted in a form approved by the press, it goes before a popular assembly meeting in at least thirty-eight places in Japan. Then it goes back to the Diet, and congressmen have access to the primary schools in their districts on Saturdays and Sundays so that they can canvass people on their views about new laws.

Whether it's Japanese popular assemblies, Swiss referendums or cantonical laws, or British parliamentarians and their surgeries, Western law is generally much more accountable than law in developing countries. Somehow or other, you are always in contact with your "dogs."

This is not, of course, to say that there's only one system. The Swiss system is completely different from yours. They've got seven presidents who take turns, while your president gets elected through chads in Florida. But one thing all of you in the West have in common: the rule of law is the rule of law because, generally speaking, people see it as fair.

Now let's get back to Argentina. Before we go through another revolution in Argentina or any other country in Latin America, we should know why the system failed. My general sense is: 1) legal property is not widespread, so there is no vested interest in keeping the legal system in place; and 2) we do not have real democracy. In my country we elect a dictator every five years who literally can issue 150,000 rules during that period (that's 30,000 executive decrees per year).

This naturally results in no small amount of corruption and mayhem. You can talk about macroeconomics all you want, but until we get the politics right and the property rights systematized, capitalism will not take hold.

Q You hold up the United States, North America and the rest of the developed world as your ideal, yet it is hard to find two states within the U.S. that have implemented our Uniform Commercial Code in exactly the same way. What about the Cayman Islands? They have codified to an extreme extent the way in which property and other assets can be transferred. How far does the developing world actually need to go to get the benefits you are describing? Does the West have even further to go?

A Regarding how much further the United States has to go: I really have little to say, not only because I am the son of a diplomat, but also because the work of my institute is dedicated to assisting poor people in a practical way. We don't want the poor to fall into the hands of dreamers who say, "No, we can do much better," or "Let's try something else." Rather, we prefer to test what actually works. The broad lessons that I draw from observing both Americans and Europeans is that when you really want to help a country, you don't throw money at it; you assist with creating a legal framework.

I tried to illustrate that through the case of Japan. After World War II, the United States wanted to break the back of Japan's feudal system, which had supported and financed its military expansion into Formosa, now Taiwan, and Korea. But there were other reasons as well for breaking Japan's feudal system. General MacArthur was concerned that Mao Zedong was coming down from Manchuria and titling collectives, a system that could have proved even more effective than feudalism.

Interestingly enough, Americans didn't remember what Mao had done when they started fighting in Vietnam, because otherwise they would have countered Ho Chi Minh much more effectively. Guerrillas and terrorists excel at titling; that is also what Ho Chi Minh did. Peru found that out with Abimael Guzman of The Shining Path. We had to out-title Guzman in the course of putting down his insurgencies. That was the only way we could win the local war. When you really want to help a nation, you have to address its legal practices.

The European Union is also interesting. In 1979, Spain was still receiving foreign aid. Then it started preparing for entering the European Union, and what happened? The European Union said: "You have to go through accession procedures, which doesn't mean we want you to change your law. We want the dogs to continue barking. We just want to make sure your law is conversant with ours."

So they said: "Okay, Frankfurt will do twinning with Madrid, which means that Frankfurt will advise you until such a point that we in Brussels are satisfied that a businessman from Germany, Belgium or France, when he comes to Madrid, gets the same deal that he would get as if he went anywhere else in Europe." These accession procedures can last from ten to fifteen years. Spain and Portugal went through it, and today Romania is going through it. And you know what? Romania is becoming developed.

Likewise with the Unified Commercial Code in the United States: each state has its own way, but they can talk to each other.

In closing, I would like to say that if you care about improving our world, you have to address the rule of law. I am not saying that no one is writing about the importance of the rule of law. I have read an enormous amount of literature from the United States, which has been extremely beneficial to the work of my institute. But not enough people are dedicated to putting these thoughts into practice. The Europeans have been making efforts on behalf of their union, and the United States made efforts in Asia about fifty years ago. The time has come to give the rest of the world its chance.