In 1994, General Dallaire was the commander of the UN Assistance Mission to Rwanda and powerless to stop the massacre of 800,000 people, who were slaughtered in 100 days. Yet just as in Rwanda ten years ago, the UN is reluctant to use the word "genocide" to describe Darfur.

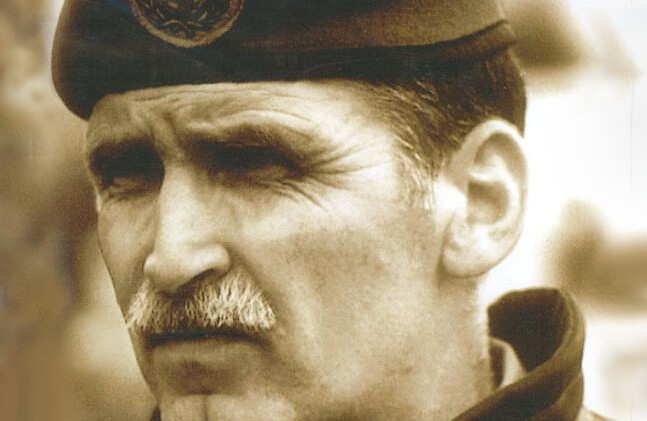

JOANNE MYERS: Good morning. I'm Joanne Myers, and on behalf of the Carnegie Council I'd like to welcome our members and guests, CNN, Diplomatic License, German ARD TV, to our breakfast program.Before we begin, I would like to take a moment to thank the Canadian Consulate, and especially Jennifer Kay, for making this event a reality.Although every program at the Carnegie Council has meaning, for me having the opportunity to once again welcome General Dallaire to the Carnegie Council is an especially noteworthy event. Today General Dallaire is here to discuss his book, Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda.General Dallaire's personal involvement as an eyewitness to history, and his willingness to share the searing experience of watching as the world's community failed to stop the Rwanda genocide, along with his own struggle to find a measure of peace, reconciliation, and hope in the aftermath, is what makes this man and his story so extraordinary.I have asked Pamela Wallin, the Consul-General of Canada in New York, to formally introduce General Dallaire. Before taking up her first diplomatic posting here in New York, Pamela was one of Canada's most accomplished and respected journalists and broadcasters. Knowing of her vast experience, first as a reporter for the Toronto Star, as a commentator for CBC Radio, and later anchoring the nightly network newscast for CTV and CBA, I know she is more than qualified to anchor our morning breakfast program.Please join me in welcoming Pamela Wallin, who will talk to you about General Dallaire. Thank you.PAMELA WALLIN: Thank you so much for your kind words. It's a pleasure to be back at the Carnegie Council with such a distinguished audience and with the honor of introducing a fellow Canadian, who is an extraordinary individual, a man who has experienced things that most of us cannot even contemplate.Lieutenant General Roméo Dallaire reluctantly lived and breathed one of the most compelling yet gruesome episodes in our lives as a global community, a massive genocide that took place on our collective watch, 800,000 people slaughtered in 100 days. Our governments and the United Nations turned away and left Roméo Dallaire helplessly to bear witness to unimaginable brutality.In 1994, General Dallaire was the commander of the UN Assistance Mission to Rwanda, which was tasked with preserving the peace between the Rwandan Hutus and Tutsis. Because of forces that the General himself will discuss this morning, he was left feeling helpless as chaos grew around him. He—and we—still wonder why.It has scarred him and shaped him in profound ways. Today, for all of the wrong reasons and some of the right ones, the events in Rwanda in 1994 have finally captured our attention. There is the Oscar nomination for the Hollywood film "Hotel Rwanda" and the recent success at the Sundance Film Festival of Peter Raymont's documentary, "Shake Hands with the Devil: The Journey of Roméo Dallaire." That is the real reality TV. The documentary won an audience award at Sundance and was personally introduced by the Festival founder, Robert Redford. And, the stories in the news about the crisis in Sudan's Darfur region are eerily reminiscent.It hasn't been an easy ten years, and the General will be the first to tell you that, but he is learning to deal with the ghost of Rwanda and he is trying to ensure that the words "never again" mean just that: never again.His book, Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda, has been called a cri de coeur for the powerless. It has been published in paperback here in the United States, and it has also just won the prestigious Governor General's Book Award at home in Canada.Currently Lieutenant General Dallaire is a Fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard's JFK School of Government; he advises governments, ours included; and he spends his life on planes crisscrossing North America to speak to all who will listen. He is a man with a mission.Lieutenant General Dallaire is also a hero for our time. He won't let us call him that because what happened, he says, represents one of the most massive and lethal failures of humanity. Still, as Canadians we are fiercely proud of him and he is indeed a hero.Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming Lieutenant General Roméo Dallaire.

RemarksROMÉO DALLAIRE: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. The book took three years to write, and it took seven years to decide to write it, and in the end, my editor had compiled a total of just under 4,000 pages, which we condensed to around 600 pages.The book is an expression of a witness to the ineptness of the world and of humanity in responding to its own. It also describes the inner workings of not only the Mission and the UN, but also the Security Council and other players outside, who had the ability to decide on the fate of the Rwandans who were in the throes of one of the most catastrophic failures of humanity.And so the title, The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda, has two meanings. One, humanity in all its sovereign states failed; it failed to recognize the impact of what was going on in Rwanda and respond to it. The other side of the failure was inside Rwanda, that is, the Rwandans themselves were able to leap from a very active, Judeo-Christian society that had been for over a century principally Catholic and Anglican; to days later throw away the teachings of all those years of "love thy neighbor" and leap into the cauldron of self-destruction on a scale and a method that still today is incomprehensible.Recently I spoke at Boston College, a Jesuit university, on the complicity of the churches in the Rwandan genocide. Although perhaps not an active participant, the church was a reference of objectivity, a reference of humanity, that came to support the power at the time. In so doing, it permitted practices in its schools and institutions that laid some of the groundwork for division and segregation of ethnicities. In nearly all of the village schools, Hutus and Tutsis were separated, with preference given to Hutu students over Tutsi students.Such practices continue to thrive in some societies. We create and reinforce differences between human beings. This reinforcement is often achieved by using one of the most dangerous tools out there, and that is the concept of nationalism. Nationalism can be a political stance and a structure that unites a country, providing it with the strength and fortitude to move forward. But it can also be the rubric under which other religious differences or ethnicities can be manipulated, by ensuring that one group has power over another, and as such preventing a nation from being totally democratic. The fundamental truth is that all humans are human and there isn't one more human than the other.The last time I spoke here, I was hoisted a bit on my own petard by an ambassador who said, "No, not all humans are the same. There are humans who have a different setting in this international community than others." I won't argue that there are those who have different skills, who are situated in places that give them more assets or more capabilities, that there are some who live in countries, such as this and mine, where we are in the ninety-sixth percentile of quality of life, and others are in the tenth percentile.But those differences, often amplified by other fundamental references—such as nationalism, religious differences, ethnicity—create a scenario that prevents all of humanity from having the opportunity to live as humans in this world.When I decided to write the book and not leave this earth, one of the principles that guided me throughout, that gave me optimism, was that I believe it will only take a couple of centuries for us to eliminate conflict based on our differences. The momentum that has been initiated and continues—through the mere presence of the debate, or interest in my book, or Hollywoodesque interpretations of horror, or simply in symposia—leads me to believe that respect for human rights will ultimately guide decision-makers and move them from a state of self-interest to a state of humanity.We will see a rapprochement between the two ends of the spectrum of humanity, where we will be terribly uncomfortable with the premise that humanity is advancing when we see that 80 percent of human beings are still suffering in inhumane conditions of mud and blood.In Rwanda, there was a true and unequivocal sense of abandonment by all of humanity in the field. This abandonment came from such mundane situations as running out of food and water, receiving no medical supplies when we were still taking casualties, or from the abandonment of the international media that became the only weapon that remained to me to influence the international community in taking notice of Rwanda.But even with sending my officers every night through the lines to get up to the border, passing tapes across the border to my troops who were in Uganda, and flying them to Kampala and ultimately to Nairobi so that the next morning they would be on a newscast—even with all that effort, with a guarantee that they would get a story every day, many of the hard data needed to explain not only the situation but how in the field we thought we could resolve it or could stymie the tide of that destruction, found itself on the cutting floor of the editors back in the great nations. The sovereign nations that make up the UN did not bring it to public attention in any substantive fashion.Although some claim that there was much more interest in Europe, I would argue that there were no efforts mobilized in that part of the world, except one case with questionable aims, and that is Opération Turquoise, which was a French-led coalition of African nations to provide humanitarian assistance. In the end, it instead permitted the genocidaires and millions of Rwandans to fall into servitude in the refugee camps on the periphery of Rwanda. That became the power structure that the extremists used not only as leverage for a few years but also as recruitment for their cause of returning to Rwanda and launching phase two, which was retaking the country and pursuing the genocide.It is also quite unnerving that the brains, the essence, the pilot light, the heart, the fundamental belief in genocide is still alive and well in a couple of European countries and permitted to continue to thrive, and even have the pretension of getting invited to international organizations to speak for their cause. That is still there, still festering, still monitoring and recruiting, with a small capability in the field in the Kivu area in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.O.J. Simpson's glove and Tonya Harding trying to kneecap her competition dominated the news media in this country and in mine for months, and as such pushed the genocide to the side as simply little blips on the newscasts. And because we are still in this mode, we can sit through a news program and be very reactive to a story in which one of our own civil rights or human rights is being abused by our judicial system or our financial system, be totally up in arms that individual rights have been abused, and yet in the same newscast see for a few seconds that tens of thousands are being slaughtered barely twelve hours away. We tend to put that in the realm of "we can't do anything, it's too big, and let's get on with something else."There was an excuse that many have articulated to me over the years, that, "We just couldn't do anything." But it is rather surprising that all of a sudden with a natural disaster versus a manmade disaster, we can provide "over-coverage" and "over-aid" for the tsunami. Seeing such a situation in which we feel vulnerable because we are all vulnerable to natural disaster led us to tangibly participate, in the belief that we could influence the scenario. But at that same time, we permitted a disaster that killed, refugeed, and internally displaced more people, destroyed more infrastructure, and saw the rape of many more women and girls in Darfur, Sudan to simply fall off the radar screen.In the framework of a program we are doing on their twenty-fifth anniversary, CNN recently asked me my opinion of the network. I indicated that because of the ability of our communications to talk to humanity globally, the instruments or the organizations that have that enormous power have also acquired the responsibility to talk to humanity and to express what humanity feels and needs and goes through.In so doing, the organization that has moved globally and has influenced others in their global reach, now has the ability to change the culture of the world. We can change the opinion of humanity now—not just a region, which is significant in itself, but actually the whole of humanity. We can shift people in their thinking with the right efforts and emphasis on international community. The organizations that now have that responsibility should not abandon humanity or parts of it because something else or one portion is being particularly tested.I told CNN, "There is absolutely no excuse, with that enormous capability, that while you are showing the incredible suffering of the Indonesians, your over-coverage was done at the expense of Darfur, done at the expense of the Congo, done at the expense of Burundi, where other human beings are experiencing on-going traumas that are still causing enormous casualties. But they don't make the radar screen anymore."If one has read the book Paris 1919 and seen who were the great players in 1919—the United States, the British, and the French, with the Italians a bit on the sidelines—one might look today at the Security Council and say, "Things haven't changed much in regards to who can make other's beds and who can make or break the futures of nations." Those same nations still hold power, but it simply was not in their self-interest to do something; it just didn't fit their cards.As I describe in the book, after six weeks of genocide, after an enormous amount of to'ing and fro'ing in the halls of the UN and in certain national capitals, and certainly a lot of screaming from us in the field, finally I'm told that:

(1) the big countries have decided that it is a genocide and that there is no debate on that;

(2) but the plan calling for about 5,500 troops to stop the genocide was still under debate.By May 17, I got the authority to reinforce and build the force, but not to stop both belligerents from fighting each other. If they wanted to conduct a civil war and fight, unless we were prepared to send in an intervention force, which did not seem to anyone to be of any value, the primary focus was to stop the killing behind the lines. By so doing, we would remove the principal arguments for why the RPF [Rwandan Patriotic Front, formed by Tutsi exiles] were continuing to fight; and once they didn't have that argument, we could then as a byproduct stop the civil war.What I needed within fewer than ten days were those 5,500 troops. Now, it took many weeks because many argued the plan, and it became quite evident, certainly in DPKO [UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations] and as I was being briefed on discussions with many of the big nations who reviewed my plan, that much of the questioning of the plan was purely stalling.One alternative was to use the same plan that was implemented for the Kurds—that is to say, set up a region in which to protect them. However, unlike the Kurds, the Tutsis were all over the country and they would have been killed on their way down.Finally authorization was granted to send the 5,500 troops. The only countries who could provide me those troops were the three big players, but also the middle powers that have not pulled their weight politically, diplomatically, militarily, intellectually or in humanitarian aid to the extent that they might. The middle powers are the countries that could, with some support from the major powers and some strategic lift, have deployed those troops and been very effective, and would have more than likely prevented the slaughter of another 450,000 Rwandans, the displacement of over two million refugees, and about a million internally displaced.But not one developed country bought into it. Not one white country was prepared to send their troops, even with that mandate. Ultimately, the first to arrive were the Ethiopians, then followed by Canada, Australia, the U.K., and the Americans. But the Ethiopians hit the ground nearly two months later in July, when the war and slaughter had been over for nearly a month.Although the great nations finally articulated the need and called it a genocide, as we seem to be doing today, no one provided the capability. That's why I say, "Yes, the UN has warts, and yes, it has complications, and yes, the panels that were just brought in to articulate reforms are essential. But no, it does not need the hypocrisy of the world powers using it as either a scapegoat or a camouflage for inaction."The Darfur scenario is a genocide, and yet the UN report says nearly everything except genocide. It is perverse that we are seeing the same type of mandate coming out of the Security Council, which is to observe and report. The African Union is being set up, after ten years of our telling them, "Hey, it's an African problem; why don't you sort it out?" They are now goaded to sort it out, and they have a mandate that spells failure—because "observe and report" means what? To whom? Will anybody take action on it? Their presence will be helpful, but it doesn't guarantee the return of the displaced and the ability to solve the difficult problems between landowners and the more pastoral group.In this timeframe, where the Security Council doesn't seem to be able to articulate the right mandate to protect—not intervene, but to protect—the Darfurians, we are hedging our bets and we are being manipulated by a very savvy government in Khartoum, using the same old methodologies of diplomatic tools and sanctions that didn't work then, that still don't work. We need a whole new generation, a whole new lexicon, to be able to solve the complex problems of today and gain the initiative from some very competent governments who are going well beyond the norms of humanity.We are fearful of a veto by a country or two to go with an intervention and respond to Kofi Annan's request. There is a solution:(1) call the bluff of those who want to veto against intervention for a genocide, and then hold them to it afterwards.(2) there is no such thing as single-nation-led coalitions outside of the UN. It is not transparent and impartial, as the UN can still be, for self-interest still dominates those powers who can do something about it.But it is high time that the middle powers—like Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, members of the G7, and a few others, who could move in; certainly the Australians, who are doing already a significant amount in their own region; Brazilians, and other members of Europe, who have in the past participated — step up to the plate and provide assets to the UN to give it alternatives other than getting the big boys involved.In this sort of stagnation of the Security Council, with people dying every day and suffering, why don't those middle powers go to the African Union and offer themselves up to an AU mandate? Help the AU mature, help it articulate a mandate, and provide it with support towards being able to handle a very difficult scenario, rendered all the more so because it is not in the interest of the great powers.JOANNE MYERS: General Dallaire, I speak on behalf of all of us here to say that we owe you a debt of gratitude for the service you have rendered, and that not only do you have our admiration for the courage you have shown, but our sympathy for what you have suffered. I would like to open the floor to questions.

Questions and AnswersQUESTION: As I look at genocide, from the politically-driven genocide in Cambodia, to racially-driven genocide in Rwanda, to clan genocide in Somalia, to religiously- and politically-driven genocide in Yugoslavia, I'm struck by its uncontrollable nature. Would you comment on the limits of military power in such a situation, given all the weaknesses and anomalies that we see in multinational forces and responsibility to their national governments as well as to the UN? How does that dichotomy work against a template of military missions laid down that troops can execute in an uncontrollable genocidal situation?ROMÉO DALLAIRE: We entered an era of disorder with the end of the Cold War, an era where conflict took on a scenario that was far more complex potentially than, let's say, the Cyprus scenario. Conflicts were suppressed during the Cold War because we put in despots and dictators to contain them. We didn't want World War III over Tanzania and its problems.In these situations of complex conflicts, the order of the day is ambiguity. It is not clear missions and it's not clear exit strategies and it's not absolutely clear objectives, and there is no set military solution as such. Using old war-time or nation-state instruments that have been used up to the end of the Cold War, and were used in the first Iraq war, using the old war diplomatic, military and humanitarian tools and the old classic Chapter VI peacekeeping instruments, we cannot meet the challenges of these conflicts of the new era, which situate themselves between peace and outright war.We have been ad hoc-ing our way through it, doing a lot of on-the-job training. What you see is a lot of tactical solutions.The military solution must be totally and completely integrated with the political, diplomatic, nation-building, and humanitarian solutions. What we need now are war fighters who don't just have the experiential skills of how to fight and how to use weapons, but who have a new set of conflict resolution skills.What I mean by that is not just being there and "do I use my rifle or not, and in what context," under very complex rules of engagement, but to be able to walk in the alleyways, to comprehend what the traumas are and what the conflict is, and to be able from the grassroots upward to articulate solutions.In an era where there's no more blue-collar soldiering, the corporal must understand what the general is thinking, because if the corporal shoots too soon and kills somebody, he could completely derail months of negotiations towards solving a larger problem.And so what is required is skill sets of anthropology, sociology, philosophy for combatants. In no way do I find that acquiring those intellectual skills renders war-fighting skills less. Generals who only know how to fight are in the wrong era, just as diplomats who tend to stay aloof and don't comprehend the impact of the full use of force are of no use, and humanitarians who want to operate under the old principles of neutrality are also ineffective.We need multidisciplinary leaders in an integrated capability, not one in which people will work because of their personalities or because there is pressure. We don't need cooperation as a principle of war. What we are trying to do is resolve conflicts, and so we do not need cooperation, we need integration.One of the greatest challenges for the military side is: how do we function in ambiguity? We can work with fighting a war. But with ambiguity how do I move away from action verbs, like "defend" and "attack" and "withdraw," which we spent years understanding in NATO, to all of a sudden in 1993 getting a mandate "to establish an atmosphere of security."What does "establish" mean? Does it mean I defend a country when I'm demobilizing both belligerents? Do I just watch? And what is an "atmosphere of security"—no weapons, or no threat of weapons? What would be an atmosphere of security now with terrorism in this country?If the diplomats and politicians cannot come up with terms, since they themselves are not sure what the full parameters are, then either we change the lexicon to a new version that gives us more definitiveness; or we learn to function and operate in ambiguity with more initiative needed.The commanders in the field in such a milieu will have an even stronger onus on assessing the risks to their troops. How far do you push them? How much risk do you take? And how much will the nation be able to sustain, for often the depth of the commitment of a nation to a mission may not be because of the hundreds of thousands that are dying from lack of water and water; the depth of the commitment might be on how many casualties we take.Mogadishu happened only months before Rwanda and spooked the world. Those sitting in the UN in DPKO, who begged and borrowed for people to come to assist us, found themselves in front of a wall where nobody in the developed world wanting to take casualties over a bunch of black people killing themselves in what easily and facilely we call tribalism—"They've always done it; it's in their genes."When I asked, "How is it possible to do that?" one extremist told me, "How dare you come and ask me how it's possible. Where do you think we learned this stuff? The Holocaust. The colonial masters used to wipe out villages completely to establish more discipline, more productivity."QUESTION: I was struck by your references to the role of the media in both being able to prevent these things happening and of permitting or facilitating reaction. I take your point about the O.J. Simpson and the Tonya Harding stories at the time that the genocide was occurring.And yet, after the genocide began, the media did wake up. I still remember the vividness of that horrendous picture on the front page of The New York Times of bodies that had been washed up, having spent days in the water, so that they had been bleached white. A cynic said, "Maybe now the world will intervene," with a bunch of white corpses on the front page of The Times. So the media was there.And yet, as you correctly pointed out, there was no intervention. Are we perhaps judging the media a bit unfairly? Can the media do more than just set the agenda? They can bring the horse to water, but what makes it drink ultimately is the political will of governments, who have a great capacity to see the media as laying out for them something they are obliged to respond to, but not necessarily to respond with decisive action. In other words, is it enough for the media to wake up to the problem?ROMÉO DALLAIRE:Statesmenship would always be welcome, particularly in this complex era, but we suffer from an incredible dearth of such in the international community. Few politicians have the humility to adjust their thoughts and their ambitions, nor the vision to articulate that, and the initiative to move not only their own nations but others and use instruments like the UN in a proactive fashion.The media in the field were magnificent, and we exchanged information so they could tell the story. However, the media cannot "Pontius Pilate" its responsibility of being the instrument to inform the general population.That's the real target, the general population, public opinion, for in a time when there is a lack of statesmanship and political structures as we know them, public opinion dominates the nuances and the minimum of a government in decision-making. Getting the information out to the general population, and holding decision-makers accountable—by continuously berating them on what is going on, what are they doing—is more crucial than a few talk shows and a couple of newscasts and maybe a favorable comment from a favorable senator.Paul Simon was in the media, the only one who fought his way into the White House to the Office of Chief of Staff. Why did no one else get through?The media has the dominant responsibility of providing the general population with the information and the responsibility of holding accountable those who have positions of authority to their decisions or their inaction. That's where it broke down. The events in Rwanda simply did not break through to such an extent as to create a momentum.I remember in Canada the African-American "return to the roots." As a French Canadian in my own country, I found this something absolutely magnificent for a minority to do. However, a year ago I was in front of the congressional Committee on Foreign Relations and the Subcommittee on Africa, and there were a number of African-American congressmen sitting there, and I bluntly asked, "Where were you in 1994? Where was the African-American powerhouse?" It wasn't still building its capability. It had matured. It was on the main scene. Not a word.But one must also remember that in a number of the European countries the media fell into line with some of its post-colonial or colonial thinking. Those that still consider that they have civil colonies in Africa simply reported as a colonial master looking at a problem, "They're at it again, so what do we do?"—versus looking at it as human beings worthy of intervention.QUESTION:Conflict resolution can be very difficult, particularly if the two sides are not necessarily committed. Most conflicts will continue until one side wins. This is one of the problems with conflict resolution on the part of UN troops. If you go into the field and you can't fight, and if one side starts shooting at you, you can't respond. Nations are unwilling to commit forces because they can't defend themselves.Another problem is that some of these feuds will not be settled until one side wins, so when the forces are removed they'll be at it again. How do you deal with that situation, presuming that there is no real desire to resolve the conflict?ROMÉO DALLAIRE: First of all, Chapter VI classic peacekeeping is passe—in fact, so is even the term "peacekeeping." We should simply speak of "conflict resolution."Secondly, a Chapter VII intervention capability is not required to influence the situation. UN forces that are equipped to respond to crimes against humanity in the field and abuses by one side or another outside of the mandate are and can be effective. My rules of engagement permitted us to do it. The only problem is that when I tried to use it, I was told it was outside of my mandate because I had smoked it into my rules of engagement.As to the actual resolution on the ground, you can move that way without necessarily having it come across as a win/lose, for reconciliation is an instrument. One hopes to establish an atmosphere in which the moderates can function, without always looking behind them and seeing their families being wiped out, as was the case in Rwanda. I was negotiating with moderates on the Hutu side, but they were never able to come to the fore because they always worried about their families.Reconciliation and instruments to build that can move the program to resolution. Empowerment of women and education of children will, in the long term, change the scenario.If there is still a lot of shooting going on, we must question the mandate and how we ended up there, but I don't believe that one must see an outright political solution or framework in order to provide protection to vast amounts of people who are simply the pawns in this exercise.I have nothing against negotiating with Khartoum, with continuing to work to convince them, and maybe even let the moderates in the government have more power, but I've got a real problem that while we're doing that we do nothing for the people of Darfur.The Document of Responsibility to Protect offers us an opportunity, maybe to not solve the operational conflict that is going on there, but to prevent the use of the general population as an instrument of war.Killing your own to achieve an objective by blaming it on the other side, or destroying your own people, or maneuvering them, displacing them, in order to gain an advantage that will help you influence someone in the Security Council are unacceptable tactics. Today the general population is and must be considered as an instrument of conflict, of war, and children in particular and child soldiers even worse.And so we don't look at the conflict as just how the politicians are working on it, nor do we look at the forces that are in conflict. What guided me in my concept when the genocide was approved was: how do you protect those who are being used in the exercise from continuing to be abused; and, if you are able to establish a certain level of protection and support there, can that not be a catalyst to solving it in the other way?The failure is that we just don't have the tools to do it. The diplomatic tools are not there, the military tools are not there, the humanitarian tools are not there, in order to make this new thinking function.My research shows that we need a whole new lexicon coming from all three of those dimensions, with a whole new set of parameters, to meet this era—which is not a blip in history.JOANNE MYERS: General Dallaire, once again I thank you for being with us.