Is Khordorovsky a captialist or a criminal, and what does his case teach us about Putin's Russia?

JOANNE MYERS: On behalf of the Carnegie Council, I would like to welcome you to our Author in the Afternoon program. Our guest is David Hoffman who will be discussing his book, The Oligarchs: Wealth and Power in the New Russia.

After the Soviet Union collapsed a decade ago, post-Soviet Russia seemed to chart a course toward democracy and a free market. It wasn't long, however, before communists were making a comeback. President Boris Yeltsin was sending tanks against Parliament; a series of self-appointed oligarchs were stealing the State; and Yeltsin's successor, Vladimir Putin, was seizing it back from them.

Once again it is election time in Russia and perhaps a good chance to assess this country's progress toward democracy. With the parliamentary elections held last month and presidential elections to be held in March, this is the perfect opportunity to look at the past decade and to reassess the forces that were so instrumental in transforming a country in the grip of failed socialism to one approaching a rapacious form of free-market capitalism.

Although Russians voted freely in December to fill all 450 seats of the Duma, it was of interest to see that so many of the candidates were the nouveau riche, leaving the distinct air that the tycoons and oligarchs were brazenly attempting to buy access to power.

The force of their power was underscored with the arrest in late October of one of the most vigorous and longest-surviving oligarchs, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, former chairman of the giant Yukos Oil Company.

Mr. Khodorkovsky's arrest has once again focused worldwide interest on this group of wealthy and powerful men who are known simply as "The Oligarchs." We're all curious to know how this handful of men were able to be so influential in shaping the political and economic landscape of the new Russia. How did they end up controlling such a disproportionate amount of Russia's economy, and how were they able to rise at Russia's decline?

To understand the age of the oligarchs, we need to begin where they began, and to take us back to that point I've asked David Hoffman to provide a tour of the past ten years of oligarchic capitalism in Russia. One could not ask for a better guide to take us through this morass, for his history of the rise of the oligarchs may, according to The New York Review of Books, just well be the most authoritative account we will ever have on this issue.

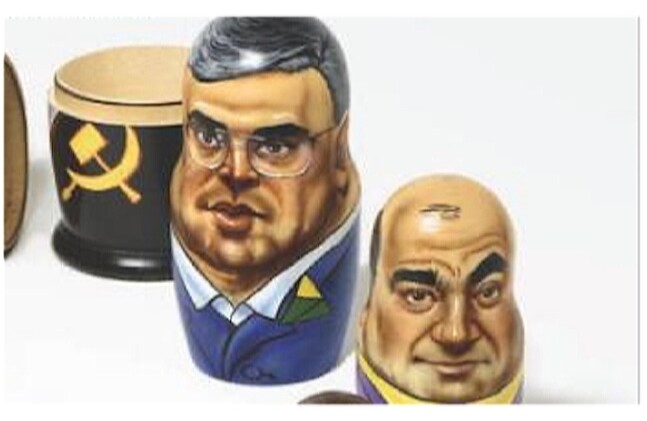

Based on extensive interviews and exhaustive research, our guest today has assembled a remarkable account of the lives of six of Russia's most cunning, ruthless, and influential tycoons. He reveals how a few players rose to the pinnacle of Russia's new capitalism, and he sheds light on the hidden lives of Boris Berezovsky, Vladimir Gusinsky, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Alexander Smolensky, Anatoly Chubais and Yuri Ushakov.

Mr. Hoffman joined The Washington Post in 1982 and covered both the Reagan and Bush Presidencies as The White House correspondent. After serving as a diplomatic correspondent and correspondent in Jerusalem, he moved to Russia to head the Post's Moscow bureau for almost six years—from 1995 to 2001—during a very pivotal time in Russia's transformation. Currently he is a foreign editor of The Washington Post.

Join me in giving me a warm welcome to our guest this afternoon, David Hoffman. Thank you for being here.

RemarksDAVID HOFFMAN: Thank you all. I will try to cover all ten years in thirty minutes, and the more time I can leave for your questions, the better for all of us. Covering ten years in thirty minutes seems slightly less daunting than covering fifteen years in 567 pages.

Rather than do the whole landscape of that ten years, I will narrow it down a bit to talk about the Khodorkovsky case. I would like to discuss what is happening in Russia and examine where Mikhail Khodorkovsky came from and why his case is important to our understanding of Russia today.

At the end I'll touch on some of the political questions, and we can deal in the Q&A with recent political events. But we understand much more about what happened in the parliamentary election than we understand about the Khodorkovsky case.

I am very interested in this case. I've interviewed Khodorkovsky extensively, including during the months just before his arrest, so I have a lot of original information to share with you. I would like to address four points:

- Who is Khodorkovsky and where did he come from?

- Why is evolution to capitalism in danger in Russia?

- What are the specific charges against Khodorkovsky and why are they important?

- What does this mean for Russia and what should be done about it?

When I first began writing about these businessmen for The Washington Post, my very first story was a profile of another one of them, and a whole day went by, unusually, before the editor called me back. He said, "I can't quite figure out this story. This fellow you've written about, is he a capitalist or a criminal?"

This question has stayed with me through the entire work on this book because, frankly, I don't have the answer, and even today we oftentimes find ourselves asking this question.

What are capitalists in a land that was hostile to the idea for seven decades? What are criminals in a state without the rule of law?

When we talk about these oligarchs, these businessmen, we are not talking about people who simply stole, because hundreds, thousands of people stole. In that period after the Soviet Union collapsed, stealing was not a major accomplishment. But building an empire, getting the entire natural resources of a country under your control, for that matter, getting the President of the country under your control, that is what it takes to be an oligarch.

In the Soviet period of shadows and shortages, entrepreneurship was considered criminal. Keep that in mind as we hear the saga of Khodorkovsky and the question about whether he's a capitalist or a criminal.

The Soviet economic system was faltering in the early 1980s; it could not deliver the same levels for consumers, especially because it was so heavily devoted to the military-industrial complex. In a last-ditch effort to recreate the dream, several members of the Politburo pushed through a resolution that would lead the fight against what they called "unearned incomes". This seemed to be a bad thing if people were earning unearned incomes in systems in which entrepreneurship was criminal.

But people didn't know what unearned incomes were. Was that driving a gypsy cab? Was that growing your own tomatoes and cucumbers? It was very puzzling when this order came out, but nonetheless the militia went down the street trying to figure out what it meant. They decided that growing your own tomatoes was definitely a crime.

They positioned themselves south of Moscow to watch for people driving up from the south to Moscow bringing vegetables for informal sales as part of the shadow economy. Nezavisimaia Gazeta, then a rather probing paper, ran the headline "The Criminal Tomato."

Out of sheer embarrassment over this episode, Mikhail Gorbachev began to change. The Communist Party undertook an experiment to allow the first small, private businesses, called the cooperatives.

The system was trying to save itself. Certainly they weren't allowing cooperatives to run steel mills or take over oil refineries, but they allowed people baking pies and doing shoe repair to start small businesses, and they gave the Communist Youth League loopholes in order to do this.

It was in this environment of uncertainty, fear, testing and experimentalism that Mikhail Khodorkovsky got his first start. All those involved with cooperatives were considered on the edge of society, hustlers and rather unsavory fellows.

Khodorkovsky's first cooperative was a disaster. He opened a little café in the lobby of the Mendeleev Chemical Institute in Moscow, figuring that when his fellow students were finished with their classes, they would stop for coffee. But nobody did. Undeterred, he continued to develop.

It's very surprising when people first meet Khodorkovsky, because for someone who is a very steel-willed individual, he has a soft and high voice that makes me think, even when I talk to him, that he's about fifteen. He's also painfully shy.

With these characteristics that masked a bit of his ambitions, he set out to start another business, to find a way to take a large amount of non-cash State subsidies which sat in various institutes and factories, oftentimes unused. These institutes and factories needed real cash, real rubles, which existed side by side as another kind of money. Real rubles were rather scarce, and you were supposed to use them only to pay your wages. You couldn't hire a truck or build a shed with real rubles.

Khodorkovsky is a very scheming fellow, and he figured out how, with the permission of the Party, to take the non-cash, worthless accounting subsidies that institutes and industry received from Gosplan and from the Center and transform them into real cash, which he then could kick back to the factory director, put in his own bank account, and use for other purposes. How did he do this? He was twenty-five years old. The Soviet Union still existed, and he discovered a way to churn the Soviet system's own subsidies into real money.

He used a tiny loophole to take the workers in any institution, call them your labor collective temporarily and pay them with this special money. He took people in their own factory, gave them a symbolic designation, and used that loophole to then say, "I have to pay them all in cash," took the subsidies, turned it into cash in the state bank, with permission, and had a lot of that cash left over for himself, for the director, and for other purposes. Soon his little bank, Bank Menatep, began to bulge with real cash, and soon after that he figured out how to take the rubles and turn them into dollars.

This is the beginning of the age of easy money, because he wasn't alone. Take that little trick and multiply it by 100, 200, 1,000. Many people were trying this, and as the Soviet Union came to an end in 1991 and the new Russia began in 1992 and 1993, the age of easy money just exploded, and Khodorkovsky and his pals were everywhere.

First of all, self-interest became legitimate in the age of easy money. We went, in a very short period, from entrepreneurship being criminal to self-interest being legitimate.

Secondly, you can have no capitalism, as Boris Yeltsin said he wanted, without capitalists. This brigade of young guys was poised and ready to step into the role of the first capitalists.

The Soviet Union had collapsed. Its laws and rules, which were written for a society in which entrepreneurship was considered criminal, were still on the books, but nobody obeyed them. The State fell apart as a regulatory institution, partly because the laws were inherited from a country that no longer existed.

Many people like Khodorkorsky hustled, and he began to accumulate tens of millions, maybe even 100 million dollars in those first years, just by playing on the weakness of the State.

You could bet on tomorrow's ruble-dollar rate today and make tens of millions of dollars. You could become an authorized banker for the state. Khodorkovsky could say, "You have to pay the teachers in Kolymskaja. You have no way to pay the teachers. I'll pay the teachers." There was no treasury in the early days of Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union, so they used the bankers, who said, "Give me $600 million. I'll pay all the teachers in the country." The State gave them the money.

What did he do with it? He didn't pay the teachers. Some of them came and knocked on the door of the bank in Moscow asking for their pay. Khodorkovsky sent out guys with guns and said, "Step back across the street, please." He understood the time value of money. Six hundred million dollars over three months could reap him a nice profit. The teachers didn't get the money until later, and sometimes he then paid them with vexels, with promissory notes, IOUs, for money he was supposed to give them.

Finally, the most critical point was the arrival of voucher privatization. Khodorkovsky accumulated as many of those vouchers as he could with his tens of millions. He in turn used them to buy interests in 29 different companies: oil, metallurgy, chemicals, food processing.

Anatoly Chubais, who was in charge of this process, had a profound assumption behind this program: If we give all the property away, ultimately the people who get it will succeed or fail on their own wits and wisdom. If we give it to them, those who fail will have to sell; those who succeed will make it to the next generation. And Chubais said, "I don't care who gets it. Let the market work. Let evolution happen, and we'll see after two or three generations that the good owners will be predominant and the bad ones will fail."

Interesting question, because Khodorkovsky quickly bought up many of these businesses, and then after the vouchers, in every company, there was 20 percent left over which the state still held.

Chubais and some of his aides were asking, "How can we get rid of this 20 percent?" because they wanted all of the property in private hands. They came up with an ingenious scheme—investment tenders.

These were an auction where the person who promised to give the most money in the future for a company's investment won the 20 percent. Property was being auctioned in exchange for a promise to invest in the future.

Khodorkovsky used investment tenders, as did every other major participant in privatization at the time, to buy these last 20 percents—very valuable because it often gave them majority ownership.

Khodorkovsky bought, for example, a little fertilizer company called Apatit. He promised to invest $238 million in it in the future.

This small group of increasingly powerful oligarchs helped get Boris Yeltsin reelected, and in exchange they got a new round of privatizations, a very small number but a large amount of property. The crown jewels were given out in 1995 and 1996—oil, minerals—and this is when Khodorkovsky gets his Yukos Oil Company, which he had had his eye on for several years.

The loans-for-shares auctions, which was part of this embrace of wealth and power, were rigged in a way in which not even Khodorkovsky could hide, because in the auctioneer was also the winner of the bids. So his bank, Menatep, was the auctioneer, and his bank, Menatep, using a front company, a shell company, was the winner.

They had a very ingenious method to keep all foreigners out, because everybody knew that if British Petroleum or Exxon came in, they would all be history. They paid very low prices. Khodorkovsky got 78 percent of a very big oil company for $300 million.

Loans for shares, investment tenders, this entire period of voucher privatization was not individual guys going into a candy store and filching a candy bar. These were actions of the State, which was giving the property away. The State set no rules, but said, "You can have factories for a promise."

After Khodorkovsky got this Yukos Oil Company and Yeltsin was reelected, there was a huge boom in Russia in late 1996, 1997, and up to the first part of 1998.

Just to give you some sense of proportion about what the guy who started out with the youth café was up to in 1997, let me just remind you that he purchased Eastern Oil Company for $1.2 billion, the full asking price. He borrowed $300 million from CSFB in October 1997 without any collateral, and then $500 million against future oil deliveries that December. He borrowed $236 million more from three European banks who said, "We're going to insist on some collateral," so he gave them 30 percent of the shares in his recently-acquired Yukos Oil Company.

All booms come to an end. The ruble crashed in 1998, and the State was once again there at his side, saying "You don't have to pay back any of your loans. We'll have a moratorium. You guys are all hurting. We sold you these bonds. The bonds collapsed, so don't pay back," and Khodorkovsky was among those who didn't pay back.

And in 1999 he became the poster boy for the worst kind of corporate governance abuses that we've seen in post-Soviet Russian history. He defaulted on the three bank loans. He told the banks, "I'm just so poor, I can't pay you back. Please?" Banks have to balance their books every year, and after a while they got tired of waiting. They sent a team in to see if he had any assets they could seize, and the team came back shaking their heads.

Early in 1999 they just figured, "We made a mistake, let's write it off." They took the paper, the 30 percent of Yukos which they held, and they sold it.

Guess who bought it? They didn't realize it, but on the secondary market he bought it all back for $100 million. Net gain: $136 million in cold cash by simply defaulting.

He also had a series of run-ins with creditors, with minority shareholders. He threatened to take the whole oil company offshore to get out from under certain debts.

Where have we come in the nineties? Yeltsin, in a decision that had profound consequences, decided with the liberal reformers to create maximum freedom first and rules later. So into this vacuum rushed chaotic forces, forces of evil—cheaters, charlatans, hooligans, criminal gangs, corrupt politicians, and oligarchs.

In the enfeebled condition of the Russian state at this time, money bought power. There was an unmistakable sequence to the accumulation of all of this property by the oligarchs and others. They got money from the easy money period. They bought property. Then they came into conflict with each other over that property and had no place to solve those conflicts because the State did not exist as a regulatory institution, so they resolved them on the street with guns. There was a terrible surge of violence in the 1990s. But the cycle was complete. Money ruled.

So what happens next in Russia? Do the robber barons go straight? And why? After becoming the bad boy of Russian capitalism in 1999, Mikhail Khodorkovsky decides he will follow the example of the American robber barons and clean up his act.

First he had to get all of Yukos back. He got 68 percent of it after he finished buying back those loans. The stock was practically worthless. They had stopped trading it on the Russian stock exchange because of his bad behavior. So he forced out the chairman of the Russian Securities Commission.

Khodorkovsky said, "What do I do? I've got 68 percent of the company, the stock is worthless, it's not trading, and it has a lot of oil." If he had kept it private and said, "Me and my six pals, it's our company and we'll pump the oil," he might have done very well by himself.

Khodorkovsky said, "If we're going to be the robber barons that went straight, we've got to do it differently." He then began slowly, and against much skepticism, to adopt Western transparent business practices. He kept the company public. He inherited a massive oil windfall when prices went up in 2000. It helped to have a couple of billion in cash.

He also issued accounts by U.S. standards. He paid dividends. And now I remind you he owned 68 percent of this company, he's paying dividends to himself, but there is the other 30 percent. For the first time, there was a major move by a Russian company to begin paying dividends.

Yukos' production soared. A lot of oil started going through the pipeline. He invested in equipment so that production would increase. He promised good corporate governance, and guess what happened? This Russian robber baron was rewarded for his good behavior. The stock began to trade and go up, and after a year or two, the stock hit 11 bucks a share. He wasn't finished yet.

I was very skeptical. I had an adversarial relationship with Khodorkovsky, I did a lot of reporting that was very difficult, with a lot of secrecy. When people said, "He's changed, and now he's going to be like J P Morgan," I said, "Right."

But over time, we began to see that the metamorphosis and evolution was real, and that it parallels precisely what we think so proudly about our own tycoons.

Khodorkovsky then took another step that no other leading Russian businessman had taken. He revealed the true ownership of his company. Khodorkovsky revealed that he had 38 percent or at that time about $9 billion worth of this Yukos Company. He got it for $300 million. Not bad for a couple of years' work.

He began philanthropy at home and abroad. And things began to happen in Russia. British Petroleum announced a $7 billion investment in another Russian oil company, and Khodorkovsky began to publicly talk about selling part of Yukos to Exxon or Chevron.

The metamorphosis was continuing. Why did it happen? It happened because there are certain basic forces of change which are very familiar to us from our own history, even from our day-to-day activities.

One of them was greed and self-interest. Another was that when all the property and easy money were exhausted, when ruble-dollar speculation was no longer profitable, people need to move into more legitimate channels to make money.

And also, there was an important moment when the owners of these companies began to do exactly what Chubais said. They began to feel like stewards. They had to hire good managers. They had to increase production and pay dividends and issue annual reports.

Where does that leave us today? Is the guy a capitalist or a criminal? The President of Russia, Vladimir Putin, missed this entire period we were discussing. In part of it he was in Germany, later in St Petersburg, but in my view he never fully understood the chaotic period of the nineties or the evolution that was about to happen and was under way with Khodorkovsky.

Putin said recently, "People are constantly saying that the laws were complex and it was impossible to follow them. Yes, the laws were complex and intricate, but it was definitely possible to abide by them. Everyone who wanted to follow them did so. Just because five, seven, or ten people did not follow the laws, it does not mean that everyone did not abide by them."

The truth is that nobody abided by them. The truth is that Russia did not become a rule-of-law state in the 1990s, and he missed that.

Khodorkovsky's fortunes changed abruptly this year. The company came under attack. He was arrested, he was accused of fraud. Some of his partners have been arrested, others have fled, and the market value of the company has gone down. He's not worth $9 billion anymore. He's now in jail.

A capitalist or a criminal? I mentioned that in 1994 the fertilizer company, Apatit, was privatized. There was an investment tender for 20 percent, and Khodorkovsky promised to put in the $283 million investment, but did not. He was not alone.

Where was the State that had set this up? After a period of litigation over Apatit Fertilizer Company, Khodorkovsky finally reached a settlement. He paid the State $15 million last year as a settlement for the promise to invest that he didn't keep. It was a civil settlement in which the criminal prosecutor also sent a letter saying, "I have no further claims."

Now, suddenly, it's the basis of a criminal complaint. Now, suddenly, Khodorkovsky is under fire. This is the core of the case against him.

This is not a question of criminal activity because what's happening is something larger. All of privatization is on trial. If the Apatit case was a crime, then pick anybody now in business in Russia and he's a criminal. If you can have arbitrary prosecution, you don't have a rule-of-law state. If you declare that all the nineties' privatization is vulnerable, then watch out, because anybody can be next. Is that where Russia should be going?

What's really behind this? People say, "Oh, it's just politics. Putin's running for election." It's a very good way to run a populist campaign. There's enormous resentment. Millions of Russians suffered in this period.

People also say, "The State needs revenues. These guys have all the billions. Why don't we just get it from them?" There's a way to do that—taxes.

People say, "Oh, Putin's cleaning up. He's going to make it a rule-of-law state." But you can't build a rule-of-law state unless you use rule-of-law methods, and these are not rule-of-law methods. The Kremlin has decided to consolidate power in both politics and the economy, where competition is the real oxygen of democracy, of capitalism. Putin has started to smother competition and capitalism, just as he's smothered it in politics with the governors, the Parliament, and the media.

There are examples around the world of places where state capitalism functions. Take a look at Mexico. Should Russia be like Mexico? Do we want a place where the state controls all the decisions about winners and losers? Is that real market capitalism?

I don't think we're going back to the criminal tomato. But I worry about whether Putin is headed to state capitalism, and certainly I worry about what's happened in politics.

What to do? First of all, we cannot disengage from Russia. All the time I was there I found very unhelpful the many people who said, "Pull back." No matter how difficult it is, the United States must stay engaged. We've invested too much in the Cold War, too much afterwards, to just say, "It's not working. Goodbye."

Secondly, it's vital to speak the truth about what's happening here. I find it very unfortunate that President Bush said recently, "I respect President Putin's vision for Russia, a country at peace within its borders, with its neighbors and with the world, a country in which democracy and freedom and rule of law thrive."

Thirdly, Russia needs to amnesty the 1990s. We need to draw the line and say, "That's done. Property rights were distributed. It's over. Now let's start. After today we will adjudicate property rights with rule of law. What happened happened." If we don't do that and all the nineties' transactions remain in play, watch out. Everybody is potentially guilty.

And finally, people ask, "What can we do?" and I would ask, "What can Russia do?" Russia needs to do these things not for our sake, because we are interested in her future. Russia needs to do these things to remain and become a competitive market democracy.

Does Russia want to stay in the G8? Does Russia want to be like the other seven countries? Or does it want to be like Mexico? Mexico is not in the G8, for a reason. Russia is, because, as it was coming out, it seemed like a good idea to include them among the major industrial democracies. But the Khodorkovsky case, the events in Parliament, the smothering of competition, are not the behavior of a leading market democracy.

Questions and AnswersQUESTION: We had heard some time ago that when Putin took over, he called seven oligarchs into his office and said, "Fellows, there are three new rules. One is you can keep what you've stolen; two, don't steal any more; and three, stay out of politics."

The thing you didn't bring up is that Khodorkovsky did become involved in politics in Russia. It's well known that in this recent Duma campaign he had aspirations himself to become prime minister. There are some oligarchs who are not in peril at this point. I'd be interested in your reaction.

DAVID HOFFMAN: You're right. Khodorkovsky himself was there when Putin made those comments. Putin said, "You can keep what you stole and stay out of my face." I understood the deal to be, don't run the Kremlin like you did with Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.

The odd thing about this promise and this arrangement is that it was never published; it was never written down. In fact we don't really know the terms. Khodorkovsky himself believed, and I believe, that he had toed the line because he didn't get involved in television—that's what Putin wanted to dominate—and his activities in the Duma, while active, were known to the Kremlin. In fact he asked their permission to make contributions to the various candidates in the Duma and they said fine.

Putin either changed the understanding or we didn't understand it well enough.

Also, since when is political activity, even scheming, intense political activity, criminal?

Khodorkovsky may have threatened Putin. Anytime you talk about selling to Chevron or Exxon, your President will be upset. But Russia had a system which suddenly went off the rails, because when Putin decided that this guy was a threat, he didn't try a windfall profits tax. That would have hurt Khodorkovsky. He didn't say, "Corporate contributions are illegal." No, in fact he sanctioned the contributions. He said, "Go directly to jail. Do not pass go." That's not the kind of Russian democracy that we had in mind.

QUESTION: You say that privatization is on trial, and the Khodorkovsky case obviously is an example of that. How much has U.S. policy colluded in the rise of the early criminal oligarchs? Some of their transformations into real corporate citizens have been successful.

Has closer American involvement at a corporate level, even at a political level, helped to encourage the very destruction, the breakdown, of the system you talk about?

DAVID HOFFMAN: You raise a lot of very complex issues. The history of American and the IMF involvement with Russia is definitely a bigger book than this one.

This evolution that I describe could be aborted now, and that's what we could be watching. What worries me is that none of the other Russian businessmen, some of whom began to be more open, have raised a finger in defense of Khodorkovsky. In fact most of them now are retreating. It is quite clear that this transparency and openness that Khodorkovsky pioneered didn't pay very big dividends.

One of the things that we did successfully in this period on a big scale was to impart the values of what market capitalism was, and we did it with our own crazy history.

How many times have I heard young guys like Khodorkovsky tell me that they watched every Wall Street 1980s movie, and they like the cigars and the suspenders.

Boris Berezovsky told me that one of the most important influences on his generation was Theodore Dreiser and The Financier. You can find every single manipulation carried out in Russia in that novel. Frank Cowperwood is the first Boris Berezovsky.

When Yeltsin and company said, "Capitalism and freedom first, rules later," we meekly said, "Okay, rules later." Others who have studied this say there's nowhere where you get the rules first and then liberalization.

In 1994 it was critical for us to say, "Okay, guys, now it's time for rules, and we're the rules specialists. We're a 200-year-old rule-of-law state. We can show you what to do." That's where we fell down.

You remember those pyramid schemes? They erupted in 1994 and then collapsed. There was not a Russian Securities Commission until after that.

QUESTION: Can I ask you to push your view of the future a little bit? You've said we're moving toward state capitalism.

DAVID HOFFMAN: Why is the aborted evolution of Khodorkovsky of interest? Take a look at the model of state capitalism in Russia today. Gasprom, the largest company in Russia, was opaquely managed, yet billions of dollars from within the company were stolen. And here's a hydrocarbon company. We can measure its barrel-of-oil equivalent relationship to its stock price. Gasprom's barrel-of-oil equivalent is about 10 cents; Exxon is about $10. Same barrel-of-oil equivalent, same hydrocarbons.

Why is Gasprom ten cents? If Gasprom were half of Exxon, you could support Russia's military for forty years. You could build a kindergarten in every other block. Why? Because Gasprom's a perfect example. It's majority-owned by the State, and it's a huge resource—natural gas—and since nobody knows how the company functions, since everybody sees the stealing, that's the future.

Pluralistic market capitalism and competition are critical, particularly at a stage where Russia is so heavily dependent on hydrocarbons.

Russia needs to diversify and to take a literate and mathematically inclined, educated population and get away from hydrocarbons. It's the only way Russia can really compete ten or twenty years from now.

But state capitalism has made it much easier to become a petro state, and that's the danger. Russia is right on the cusp because if oil prices go down, they'll begin to feel it. This is an illusionary period where oil prices are so high.

QUESTION: Is there any chance that Putin will lose this case?

DAVID HOFFMAN: I've looked as closely as anybody can at the case. There is a 30 to 40 page indictment which I've read. But the way the Russian system works is that they've presented Khodorkovsky with all the documents in his case while he's in jail so that he can study them and be prepared to respond for his trial. It is 227 volumes. If you look at the bare-boned indictment, it's possible that they could win because there is no rule of law, and it's possible that any judge will be responsive to an appeal from the Kremlin. It would be very popular to convict Khodorkovsky.

But looking at the specific charges in the case of Apatit, the fertilizer privatization, the question of corporate tax and personal tax responsibility, all I see is that standard procedure of the 1990s is now being criminalized.

It was the State that handed out this property, set the conditions and allowed rigged auctions. And now a new man comes in and says, "That was criminal."

That's arbitrary prosecution. They could win it.

QUESTION: You've had a chance to observe Vladimir Putin during all of this research. What can you tell us about the sophistication of this man in his understanding of modern economies, in his ability to understand the complexities?

Here's a fellow who has had only one overseas tour in East Germany, which was not a very advanced economy at the time. Many of his actions are not very sophisticated, not grasping the complexities of a modern economy.

DAVID HOFFMAN: I take a little more nuanced view. He understands the goal of modernization, but he doesn't know how to get there.

You can't build a rule-of-law state unless you use rule-of-law methods, and the same goes for the economy. And here you have the paradox that Putin has put into place - with the rubberstamp Parliament that existed before these elections - the most important revisions of Russian legislation in the history of post-Soviet Russia.

I'm speaking of the new joint stock company law, which obliterated some of the loopholes Khodorkovsky used; land reform, bankruptcy, labor law, criminal procedures—all very important, progressive, modernizing legislation that a state needs. And he hasn't figured out implementation, because he routinely stomps all over his own legislation. I worry about the gap between desire for modernization and poor implementation of legislation.

Putin seems to personally share the envy and resentment of most of his countrymen at the rise of the oligarchs and their extraordinary wealth. He is now exploiting that quite publicly for the election.

He's giving conflicting signals. He posts things on the Internet and makes speeches that we could all subscribe to. Watch what he does as well as what he says, because what he does is much more worrisome and it's smothering competition.

QUESTION: If you were Putin, what would you do in order to overcome the problems that you are articulating?

DAVID HOFFMAN: First, I would amnesty the 1990s property redistribution. I would say that as of a certain date, people that hold the property will not be tried because we were complicit.

I haven't seen any bureaucrats, not one law enforcement official, arrested in the Khodorkovsky case. I haven't seen anybody who handed out property thrown into jail. Establishing the right to property would be a good place to start.

Secondly, I would say, "Today's a new day. We are going to build a rule-of-law state." Russians would go for that.

Putin when he first came into office talked about "the dictatorship of law," and to me that's an oxymoron

Next, I would think of the oligarchs as opportunity, not opposition. Khodorkovsky started a philanthropic foundation which, after George Soros pulled out, turned out to be the largest private philanthropic organization in Russia. It was doing things that Putin's state couldn't do.

I would have said, "You're welcome to keep your winnings. There's going to be an amnesty. We're going to enforce the laws. And you need to quadruple the amount of money you're devoting to the social sector."

And finally, I would have imposed an oil windfall profits tax, a public, straight tax, and it would say, "You had $4 million in windfall profits last year. We're taking $3 million for the people of Russia. You can keep one."

QUESTION: Does this cleansing of the Russian oligarchs have to do with his interest in creating more territory for another group of business people for whom he feels more sympathetic because they come from a different region or represent a different generation? This is a popular opinion which I have heard voiced when I visited Moscow and St. Petersburg in particular.

DAVID HOFFMAN: From my observations, economic and political freedom go together, and the same is true about building a strong and powerful state.

I invite you to look around the world and ask yourself, where do economically powerful states get that power? They get it from competition and they're competitive. Why? In some cases they have things to offer the world like oil and gas, but oftentimes it's because they build multiple layers and diversify, and therefore, in good weather and bad, they can be strong economically.

Just because Khodorkovsky is in jail does not mean that oligarchic capitalism has suddenly disappeared. You used the verb "cleansing." It is quite possible that if Putin wants to create an environment where he can pick all the winners and losers, state capitalism, then he is just picking another set. And that doesn't get you anywhere toward the evolution that will create a powerful Russia.