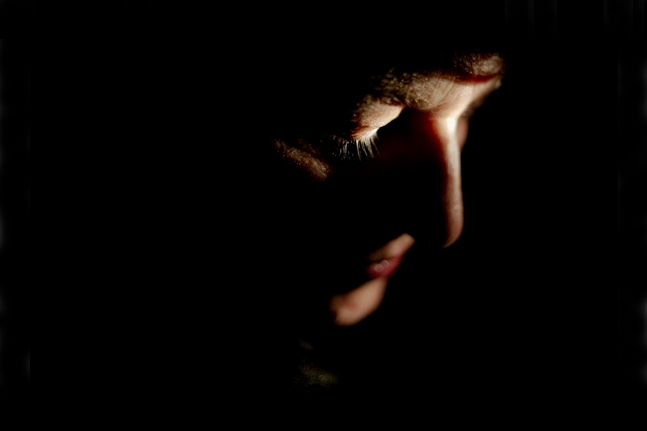

Republished with kind permission of the author. The article was originally posted on PassBlue on July 6, 2014. The photo is from a book, Sound of Silence, which the UN helped to produce. © Armin Smailović.

SARAJEVO, Bosnia and Herzegovina — "Please don't let the world forget us again."

The plea is heard everywhere by men as well as by women in the picturesque Balkan city of Sarajevo, the site of Europe's most destructive and sadistic conflict in more than half a century. Sarajevo was briefly in the news again at the end of June as people from around the world came to mark the assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand 100 years ago, the trigger that set off World War I.

But when they ask not to be ignored, Bosnians are not talking about that moment in 1914. Their crisis was much more recent.

Sarajevo, vulnerable in a valley surrounded by mountains—the site of the 1984 winter Olympics—suffered the longest military siege of any civilian population in European history, survivors say, as they tell stories of almost four years from early 1992 through 1995. Whole neighborhoods were flattened by Serb artillery in the hills, and snipers picked off desperate people who were trying to escape or merely venturing out to find some food or water.

For the women of Sarajevo and other, smaller towns around the country, a remnant of the old Yugoslavia formally named Bosnia and Herzegovina, it was a long, unrelenting dark time of horror. Tens of thousands of Bosniak and Croat women, mostly Muslim but also Christian, suffered vicious torture and sexual abuse in what became known as "ethnic cleansing" by Bosnian Serb forces and their backers in neighboring Serbia. Rape camps were set up where women, many of whom had lost husbands and sons and saw their families torn apart, were taunted by abusers who crowed about destroying or polluting Bosniak ethnicity.

Though Sarajevo was a cultural capital where ethnic peace had held for many years, the majority of the population was Muslim—the group known as Bosniaks. The Serbs are Orthodox Christians and Croats, mainly Roman Catholic. Jews who had established handsome synagogues over centuries are now few in number.

Among those who survived shattering episodes of intense brutality was a woman named Enisa, who still does not want her family name made public. Only in recent years has she talked about her ordeal: the execution of her husband, multiple rapes, and the flights from place to place to save herself and two young daughters. Summoning the courage to keep alive the unending stories of Bosnia's abused women, many of whom remain physically and psychologically damaged, Enisa began to speak out. Educated before the war as a social worker, she eventually became president of the women's section of the Association of Concentration Camp Torture Survivors of the Canton Sarajevo.

Although she now lives in a cramped flat in Sarajevo, Enisa's story began in the town of Foča, where painful memories still live.

"Our youth has gone and the town where we all once used to live together is gone," she tells audiences gathered to hear her accounts of Bosnia's women. Although the Bosnian rape camps were well known among international human-rights organizations, there have been attempts to deny their existence or erase that part of history. Abused women have almost no institutional support in a country now rigidly divided into Serb and Bosniak-Croat areas. Enisa was angered and emboldened by the Serb denial of rape camps and subsequent failure to punish most perpetrators of sexual abuses, even in the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, where relatively few accused men have faced war crimes charges for such abuses.

"I want to speak in the name of those women who suffered even worse horrors than myself and who are still unable to reveal them," she says in talks.

I met Enisa in Sarajevo in 2010 while writing a United Nations Population Fund "State of the World Population" report on women in conflict and postconflict situations. She then became the subject of a UNTV video documentary. Last year, she was featured with two other Bosnian women in a powerful new photographic book, Sound of Silence, published in Bosnia with support from the Population Fund, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon's Unite to End Violence Against Women campaign and the Norwegian embassy in Bosnia. The book is not for sale to the general public.

An image by the European photographer Armin Smailović, who documented the progress of three women who are recovering from the Bosnian war.

Armin Smailović, a well-known European photographer whose evocative pictures form the heart of the book, followed several women for three years to document their progress. He describes Enisa as one woman who has made the transition from victim to survivor to heroine. She was helped through the painful, emotional process of healing by Majda Prljaca, the Population Fund's communications officer in Bosnia and an editor of the book. Enisa now speaks to audiences, mostly of women, in Europe and abroad, repeating her call for meaningful compensation and an end to neglect by the government. But on this issue and many others, the country's national government is paralyzed.

The sharp division of Bosnia-Herzegovina into Serb and Bosniak-Croat administered regions with a weak central government was a result of the 1995 Dayton Peace Accord negotiated by the late Richard Holbrooke. At the time, Bosniaks and Croats under siege welcomed the end of the daily shelling, even though it was clear from the start that serious compromises had been made in allowing Bosnian Serbs a virtual veto over any future federal action. Even international environmental treaties and agreements cannot be ratified by the dysfunctional parliament.

In Bosnian eyes, the United States walked away from the Dayton accords and never forced implementation of steps toward a genuinely multiethnic country. Internationally, political leadership of Bosnian affairs was turned over to the European Union. Many Bosniaks are scathing in their criticism of the European performance and suspect that an anti-Muslim prejudice among European nations lies at the heart of what they consider neglect. Neighboring Serbia (patron of the Bosnian Serbs) has moved toward membership in the European Union, and troubled countries such as Bulgaria and Romania are already members, while Bosnia has not been put on track for membership.

Meanwhile, thousands of European and American tourists who are filling Sarajevo's hotels are surprised to see a modern city and secular society living among great architectural and artistic monuments from centuries of Ottoman rule, overlaid by decades of Austro-Hungarian culture. Vienna-style sidewalk cafes line pedestrianized streets. The city also has a magnificent Orthodox cathedral, a reminder of more tolerant days. Two handsome synagogues remind visitors of the dwindling numbers of Jews.

Regional experts who spoke in Sarajevo on June 28 to a symposium organized by the New York-based Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs (where I am on the board of trustees) foresee a potential worsening of Bosnia's political situation in the future. Ivo Banac, a Croatian scholar who holds an emeritus professorship at Yale and is a human-rights and environmental protection leader in neighboring Croatia, spoke at the symposium about Russia's increasing influence in the Balkans, including growing control of energy supplies at a time when Bosnia is trying to restore an industrial base to create jobs in a country with very high unemployment, especially among the young—some say as high as 50 to 70 percent.

Banac's comments were echoed by other regional speakers, who also drew attention to the danger that the Serb part of Bosnia-Herzegovina will declare independence, or even reunite with Serbia, aided by Russian support. Furthermore, European reluctance to accept an even nominally Muslim-majority nation, with fewer women in head coverings than found in numerous places in France, could drive some Bosniaks into more radical Islam, whose proponents are waiting in the wings and have been reported proselytizing in remote Bosnian villages.

The prospect would be bleak for all Bosnians, especially Bosnia's women, who fear more years of vulnerability surrounded by Serbs with powerful friends in Moscow, as well as the specter of Islamists at the gates.