Prologue

It's a usual day in early June and the farmers of Yehla are looking skyward for signs of monsoon. The fields are ready for sowing, if only the rain gods would shower their blessings. Anticipation rises in proportion to the humidity, and apprehension runs along sweaty brows. Deciding when to sow is a gamble: too early and the seeds may not germinate, too late and one misses the wet spell.

The changing government forecasts don't help matters much, and the thermometer in Pusad, the nearest town, has not been repaired for ages. A few days prior, many farmers bought seeds from the black market at well above the government-authorized prices. The government has reduced fertilizer subsidies and consequently even official fertilizer prices have soared by around 30–50 percent compared to last year. The only thing constant in this chaos is the moneylender's rate of interest—five percent per month!

Ganpat Pathade is 70 and illiterate. He got his soil tested a few weeks ago and has stocked the recommended fertilizers and soybean seeds a week in advance, at government authorized rates on credit at zero percent interest. For the first time in his entire farming life, he has visited neither moneylenders nor banks. At around 7:00 AM, his daughter-in-law reads out a text message from Reuters Market Light (RML) predicting a 75 percent chance of medium rain later in the day. Alerted by the message, he heads to the farm, treats the seeds with organic supplements, which he has agreed to use on an experimental basis over an acre of land, and sows them with confidence. He is one of 52 proud Asmita farmers.

Introduction

The Vidarbha region in western Maharashtra is just an hour's flight from Mumbai—the commercial capital of India; an India whose GDP is growing at seven percent even in times of global recession. Yet Vidarbha makes headlines for being the epicenter of crop failures and farmer suicides. As per the available data, more than 7,000 farmers from Vidarbha committed suicide during the three-year period from 2005–2007. The reasons put forward are sometimes factual (relative absence of irrigation facilities), sometimes social (debt caused by costly weddings and dowries), and sometimes outrageous (the promiscuous nature of their wives).

I always wanted to find out the real reasons behind the farmers' plight. In 2010, my friend Girish Dixit and I decided to conduct a grassroots study and analyze farming as a business process. We collected data from more than 50 farmers in Pusad taluka (a town and surrounding villages) and studied their finances and mentalities. We concluded that although farming in itself is a profitable venture, the farmers suffer losses due to financial leakages at almost every stage of farming.

The worst hit are the small and marginal farmers. The schemes and subsidies intended for them are diverted to the bigger farmers. Due to the lack of proper paperwork and bureaucratic liaisons, most of the small farmers raise capital from saavkar (moneylenders) whose interest rates are as high as 5–10 percent per month. For a crop of five-month duration, they have to pay back 1.5 times the principal. The black market is rampant. Some brands of cotton seeds are sold at a 200 percent premium, causing mini-riots.

Most of the farmers are not well educated and remain unaware of scientific crop management. They are often misguided into using excess fertilizers of the wrong kind, increasing costs while adversely affecting productivity and soil health. After harvest, the market agents demand extra commission for cash payment and the monopolistic traders offer low prices, taking advantage of the financial urgency associated with the hand-to-mouth existence of the small farmer. These practices rob the farmer of his hard-earned profit and keep him entrapped in a vicious debt cycle.

The Asmita Solution

IDEA: The results of our survey startled me as the solution—at least the short-term part of it—seemed simple and practical enough to implement right away:

- Identify the points of financial leakages and find ways to plug them.

- Concentrate on the most critical mass—small/marginal farmers and the landless sharecroppers.

- Provide an ethical atmosphere eliminating exploitative practices of money lending and black marketing.

- Stress farmer education over production and imbue them with a habit of efficiency—reduce costs and improve profits.

- Isolate the farmer from the market malpractices by providing a parallel market.

- Economic stability is the key to development. Don't impose any developmental paths on farmers (organic farming, dairy business, etc.). Once they are economically stable, they will find their own routes like a flowing water stream.

- In the long term, once the farmer is economically stable and mentally confident, introduce enterprises like allied businesses and value additions.

- Most importantly, develop a sense of identity and self-esteem in the farmers and give them confidence that farming can be profitable.

This last point was why we chose the name "Asmita," which means identity and self-esteem in Marathi, the local language.

MODEL: Based on the above framework, we designed the Asmita model which can be concisely described as follows:

- Only small farmers are eligible to become Asmita member farmers. Our rule of thumb is three hectares or less of total land holdings. However, it is stretched in cases of genuine necessity.

- The member farmers are provided with essential facilities like soil tests FREE OF COST to explain to them the hazards of rampant fertilizer use and develop a habit of need-based fertilizer supply. The focus is on changing their psychology and reducing their fertilizer costs as well as preserving soil health. None of the recommendations are mandatory and the farmers are given a chance to learn through their mistakes (by comparing with other farmers who followed the recommendation) rather than compulsion.

- The members who have access to mobile phones are provided with the Reuters Market Light (RML) service which gives them reliable local weather forecasts, crop advisories, and market rates at local markets for their crops. The subscription fee is paid by Asmita.

- The members are provided with their choice of quality seeds and fertilizers at government authorized rates on credit at zero percent interest. This eliminates the need for raising capital from the moneylender and isolates the farmer from the black market.

- The farms are visited regularly by Asmita staff and the farmers are taught scientific management, such as controlling pests in the early phase to ensure less use of chemicals, reduced costs, and improved yields.

- The harvest is bought right from the farms (or house) on a day of the farmer's choice at the market rates prevalent on that day. Thus the farmers get to benefit from market dynamics and, unlike contract farming, don't feel shortchanged. The farmers save on the market commission as well as the transport costs.

- Asmita takes a 5 percent service fee to cover its operational costs, deducts the initial inputs costs, and pays the rest to the farmer in cash at the time of buying.

- Asmita then forward trades the produce depending on market projections and makes some profit to sustain and grow.

- As Asmita's profit is directly linked to farmer yields, it is a perfectly symbiotic model where farmer and Asmita grow hand-in-hand.

The Journey So Far—Results of Pilot Phase I

Asmita started its journey in 2011 with a pilot phase involving 19 farmers and 56 acres of soybeans. Two tribal villages of Yehla and Chilwadi in Yavatmal District of Maharashtra were chosen. It was funded by my and Girish's personal savings (and money borrowed from our parents) in the ratio of 75:25. The total capital investment was Rs. 700,000 (approx. $13,000).

The initial farmer response was lukewarm. Having been conned by so many schemes in the past, Asmita was just too good to be true. The 19 farmers who eventually ended up as Asmita members were the neediest ones. Other villagers laughed at our members saying Asmita will eventually loot them. People in the town, on the other hand, laughed at us saying the lazy farmers would eventually loot Asmita.

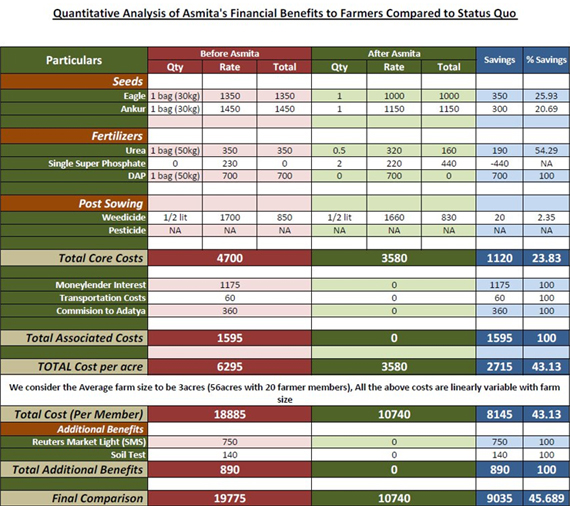

The results however shut many mouths and even we were surprised by the huge impact Asmita's simple model had on the economics of the small farmer. Without giving anything for free or at a subsidy, farming costs were reduced almost by half as shown in the following table:

Despite the cost cuts, the average yield increased around 20 percent compared to the previous average (5.3 quintals per acre from 4 quintals per acre), more than doubling the average net profits from Rs. 3,000–4,000 per acre to Rs. 8,000 per acre. The highest yield was 8.7 quintals per acre.

Asmita covered its capital investment in the first year and made a respectable 5 percent profit despite the inefficiencies associated with the pilot phase and no prior agricultural experience.

This year Asmita has started with "Pilot Phase II" and expanded its operations. The expansion was funded by an investment of Rs. 400,000 ($7,000) from friends who followed our journey through Facebook updates. We are working with 52 farmers (who unlike last year queued to become our members and were rigorously screened for their eligibility and need) and covering 140 acres of soybeans. The farmers are more confident and some landless farmers are even sharecropping for the first time in their lives due to support from Asmita.

Many of our farmers have closed accounts with moneylenders permanently while some are investing in farm improvement. Overall the boost in their morale and the positivity in the air has to be experienced to be believed—it is the main aim of Asmita.

The Road Ahead

Having covered the operational and farmer benefit part of things, we are concentrating on the long-term sustainability of the Asmita model and making it attractive to investors. We are trying to achieve a balance where the investor gets 5–10 percent annual return on their investment along with the satisfaction and knowledge that their money is helping the needy. In the long term, value addition and processing units are on the list to improve profits for the farmers and Asmita, and to reduce dependence on trading as the primary source of revenue.

We want Asmita to have the benevolence of an NGO with the aggression and efficiency of a profit-making venture.