What do Americans think about the role the United States should be playing in the world? How do they conceive of the different trade-offs between domestic and international affairs, among competing options and sets of interests and values? The Chicago Council on Global Affairs' Dina Smeltz and Eurasia Group Foundation's Mark Hannah share the results of surveys from their organizations in this conversation with Senior Fellow Nikolas Gvosdev.

NIKOLAS GVOSDEV: Good afternoon, everyone. Welcome to this Carnegie Council webinar, which is going to look at an important question that has been hovering at the margins of the election campaign for 2020.

I'm Nick Gvosdev. I'm wearing my senior-fellow-at-the-Carnegie-Council hat for this event today, and I would like to welcome you to this discussion that we're going to be having with Dina Smetlz, senior fellow at The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, and Mark Hannah, from the Eurasia Group Foundation.

Those who have seen or heard me earlier this year have perhaps noted that I said that I think the 2020 election in many ways is a foreign policy election, in the sense that the American people, both in the Democratic primary and then in the general election, are being offered real distinct choices in the types of engagement that the United States would undertake in the world, questions about our relations with allies and partners, questions of burden-sharing, and questions of promotion of American values and democracy.

If that's the case, it's useful to understand what the American public actually thinks. What do voters think about what America's role should be in the world? How do they set priorities? What are their risk tolerances for American activity? The related question is: Will this have an influence on the positions that are taken by presidential candidates, by the two parties and their platforms, and by their congressional candidates?

I think we have a wonderful discussion for you today because we have two people who have been looking at this issue and not just doing it from the Washington, DC, approach of speculating about what people think—and usually experts in Washington will say what they think and then take their views and extrapolate that that is what the American public wants or desires—but instead have been looking at survey data, polling data, focus group data, and trying to dig down beyond just the bumper stickers of "American leadership" or "America should play a role in the world" to try to really understand where the U.S. voting public is in 2020 on these questions.

I'm going to be putting full biographies in the chat for Dina and for Mark, and will also put in the chat the links—if you haven't already seen them—to the surveys done by the Eurasia Group Foundation and by The Chicago Council, so that you have those resources available, as well as the work that has been done by the Project on U.S. Global Engagement by the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, so that you will have all of these resources available.

Dina, if I can turn to you first, to get a sense of what you're finding and what your results are coming up with. Is there anything that has surprised you from the results? And Mark, then the same question to you, what you're finding in your research and what you're discovering. Then, both in your initial remarks and also in our discussion, the implications, the "So what?" of all of these questions. Why does it matter, and will it have an actual impact on the election and on policy?

With that, Dina, if I can turn the floor over to you. Take us away.

DINA SMELTZ: Thank you so much for inviting me to be part of the webinar, Nick. Mark, it's always great to share a panel with you. Our results have a lot of overlap as you'll see and as we present our key findings. I put together just a couple of slides. I'm going to share a screen and hope the magic works.

Our survey was conducted last summer, 2019. A lot has changed since then obviously, but generally public opinion on foreign policy tends to be pretty stable, and our surveys—most of the figures I'm going to show you are long-term trends—show that attitudes remain fairly constant despite shocks like the September 11 attacks and the 2008 Financial Crisis.

The key takeaways from our survey were:

- Americans think the United States needs allies and partners to solve global problems.

- They want shared leadership; they don't want to be the dominant leader. This goes against some of the Trumpian messages of "America First."

- A majority support international engagement in the world.

- And, as the title of the report implicates, they reject retreat.

What "retreat" means is that they reject not taking part in world affairs, it does not mean that they want to be involved militarily in every engagement. They are reluctant to use force generally, and they want to avoid long-term entanglements abroad.

But, one of the key findings we have found since 2015 is that Americans are growing even more supportive of defending an ally if an ally is threatened. With a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) ally or like South Korea, they would support sending U.S. troops to help defend them. This sense of security commitment has arisen since 2015, and it is the most stringent measure of commitment to an ally.

I'm just going to show you a couple of key exemplary figures. This is a long-term barometer of international engagement that we have used since 1974, but it actually goes all the way back to 1946. There are some ups and downs, but in general between 6 and 7 in 10 Americans tend to favor taking an active part in world affairs. The most recent, 2018 survey found over 7 in 10. It's as high as just after the 2001 al-Qaeda attacks on the United States. So people, instead of buying into the withdrawal argument that the administration sometimes makes, have become even more supportive of taking part in world affairs.

When we asked Americans what foreign policy tools make them feel safest, they say, first of all, U.S. military alliances with other countries, then secondarily maintaining U.S. military superiority. There are a few other things, but those were the top things; 8 in 10 also say that the United States should maintain or increase the U.S. commitment to NATO, and 73 percent say that NATO is essential. That was the highest recorded level since 2002, when we first asked it.

Again, maintaining U.S. military superiority is not necessarily to say that they want to use their muscle militarily. The other results taken together show that Americans see it more as a deterrent rather than actually wanting to get involved in every crisis militarily.

I had said that, since 2015, support for coming to the defense of a NATO ally or South Korea has grown. In 2017–2018 North Korea was seen as much more of a threat. That's why it was higher then, but it's still a majority, and you can see they have both risen since 2015. Even if China initiates a military conflict with Japan or if China invaded Taiwan, it's just minorities, but they have also risen in the last couple of years.

The two areas where we might see—and I'm curious to see whether there are changes now from 2019—are on trade and on China.

Regarding trade, I don't know if you guys saw the recent op-ed in The New York Times by Robert Lighthizer, who said that the pandemic has revealed a U.S. overreliance on other countries as a source of critical medicines and medical supplies and that "the public will demand that policymakers remedy this strategic vulnerability."

We'll see. I don't know if that's the case, but before that, in 2019—this was one of the surprising findings for me—support for international trade had surged, even higher than in 2018, which was really high. This is now—among both Republicans and Democrats—a large majority.

It doesn't mean that they agree on the way we should go about trade policy. For example, a majority of Republicans think that tariffs against China are effective, and a majority of Democrats do not. But this is one area that I think could be affected, so we'll see.

The other area that might be affected is China. In 2019 we found differences between Republicans and Democrats on the threat of China. It had risen to 54 percent among Republicans but was still low. Recent Pew polls have shown that Americans have become more unfavorable—both Republicans and Democrats at 60 percent unfavorable toward China, which was an increase—and they also are very critical of China's handling of the coronavirus. They're not full of praise for our [handling of the coronavirus], either; only 47 percent think our own country did well, but 64 percent thought that China was doing a poor job. So China might be an area where we see additional shifts.

That's basically what I wanted to show you in terms of the figures. I think that in today's world COVID-19 has perhaps highlighted the interdependence of the United States with the rest of the world, and that shows both the risks and the benefits of globalization. We're going to go into the field next month and explore both sides of that. I think the situation could underscore the necessity of working together on problems that cross borders.

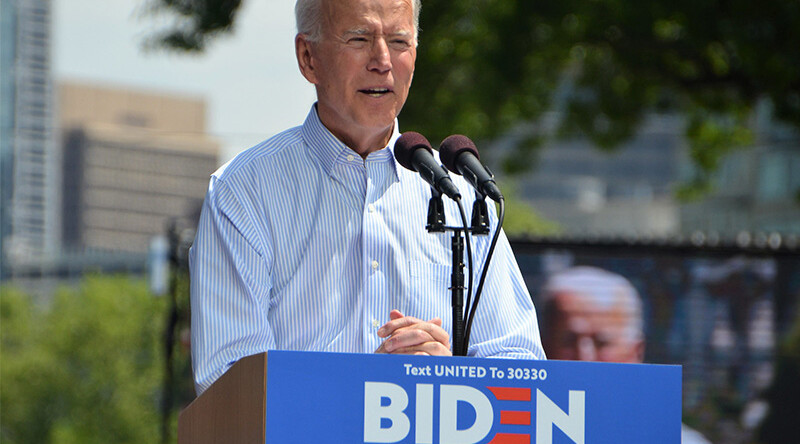

A Pew survey actually showed that 68 percent found that the United States should do more to help solve global problems in less developed countries now, so they just asked that question. The pandemic may have brought in an individual's concept of national security in a way that ties what's going on in the world to their own lives and their personal security today in a way that was very difficult perhaps for policymakers to articulate to them. The Center for American Progress did a survey and found that was one of the key messaging points that I think the Biden campaign has picked up on to some extent: How do you connect foreign policy to everyday people's lives and make it important to them? This is one very clear way you could do that.

At the same time, it could make some people want to close off from the rest of the world, including supporting bans on travel, immigration, and trade, and that is another way that public opinion could go. That's what we will test this summer, and I think I will stop there.

MARK HANNAH: Thank you, Dina. That was very illuminating. I'm a big fan of The Chicago Council's work and the fact that you are a colleague doing this important work.

I just want to take a quick minute to discuss the importance of surveying public opinion in the first place because I do think there is a sense in Washington that we're in this moment where expert opinion is being criticized and that somehow we're placing too much importance on public opinion. No question, when we're dealing with issues of war and peace and highly complicated and technical foreign policy and national security topics we don't want to run American foreign policy by referendum. We saw what happened with Brexit, we see what happens when there is a direct-democracy approach to what we do in the world.

But the Eurasia Group Foundation takes very seriously the importance of engaging with the public. It's not simply explaining the rationale for doing certain things in the world in the name of the American people, but it's also relying on the consent of the governed, which is a prerequisite of democratic politics. We do think and believe strongly that there has been a way in which official Washington decision-makers have become insulated from public opinion, largely because these topics are so mystified and mystifying.

Nick, you said at the outset that 2020 might be the "foreign policy election," and in some ways the two candidates are offering different views of America's role in the world.

But on another hand, every time election season rolls around and you ask ordinary Americans what issues they care most deeply about, terrorism might be on the top-ten list, but for the most part they're pocketbook issues, economics and things like that. This isn't to blame the foreign policy establishment for that insulation. There is a way in which political leaders aren't necessarily penalized politically for running afoul of public opinion.

But in order to shore up the engagement between the public and policymakers and to alleviate some of the mutual suspicion that I think does exist between the two, we wanted to understand what the American public thinks. In some ways our data is similar to that of Dina and The Chicago Council, even though our interpretation or conclusions might differ.

We, like them, found that if, for example, a NATO ally were to be invaded by Russia, a slight majority, just barely over 50 percent, of Americans would support a military intervention to defend a NATO ally. We saw that as a sign of lack of appetite for military interventions.

I will also say from the outset here that The Chicago Council's survey is much more broad and ambitious and deals with issues of climate change and economic policy in a way that ours does not, so we are limited on that front and also goes back 45 years and has great longitudinal data. We're a new organization, and we have just done this for a couple of years now.

The title of our survey is "Indispensable No More?" One of our main findings, when we analyze our data from topic to topic and look at very specific questions of policy, is that the American public has very little interest in an approach to the world that resembles the conventional bipartisan wisdom within Washington.

So when you're talking about the war in Afghanistan the most popular answer option for "What do you do with the current situation in Afghanistan" and our troop presence there; when you talk about American exceptionalism, in the last year alone identification with America as an exceptional country has dipped significantly while the amount of people who think we are exceptional for what we represent has—support for American exceptionalism continues to be driven by understandings of America's example, not so much with its behavior in the world—35 percent more of our respondents . . .

Like The Chicago Council we did a national sample. We conducted ours in late July, and they did theirs in June, so it's great that we have these data sets because they're sort of synchronized, and we can look across them. But 35 percent more Americans think that the United States should decrease rather than increase its military presence in East Asia as a response to a rising China, and it's almost twice as many Democrats who think the United States should decrease its military presence in East Asia and rely on and encourage our allies to become more self-sufficient when providing for their own security needs.

More than twice as many Americans want to decrease as increase the defense budget. Still the most popular answer choice is to maintain it among the broad population—about 45 percent of Americans—but the remainder, twice as many wanted to decrease.

There are partisan differences. One thing we did—and I know The Chicago Council did as well—was to analyze our survey respondents by partisan affiliation. So immigration remains very much a primary concern of Republicans, while the rise of authoritarianism preoccupies Democrats.

One thing we noticed between 2018 and 2019 is that fear of economic damage caused by trade disputes increased across both parties. I hope we do get a chance to delve into some of the topics here. Again, our survey focused much more on specific issues where the possibility of military intervention exists, so NATO alliances, the threat of a nuclear Iran, China's rise, Afghanistan.

It's interesting because I draw on some of the data in The Chicago Council survey when I'm trying to validate some of our own findings. The Chicago Council has a finding that 27 percent say that military intervention actually contributes to U.S. safety. So I think there is a sense that while the title is "Rejecting Retreat" that "retreatment" in the literal sense is not well loved or tolerated by the American public. But I hope that's a discussion we can get into.

One other thing I want to put in there as an asterisk is that there seems to be this bipartisan consensus in Washington around what America's foreign policy and national interests are. That's not always shared by the public. In fact, we asked our survey respondents about which country presents the biggest threat to peace in the Middle East, and Republicans were about 13 percent more likely than Democrats to choose Iran, and Democrats were about 10 percent more likely than Republicans to choose Saudi Arabia. So when we're looking at these two main power players in that region, Iran was still the top vote getter whether you're Independent, Democrat, or Republican, but we're starting to see differences through a partisan lens among voters.

To bring it back to your point, Nick, about wanting to discuss this in the context of the 2020 campaign, that has implications for who's trying to get which votes in 2020. The kind of China-bashing that we're seeing and this talk of a new Cold War with China is a perennial topic we see every four years. There's no political disincentive to throw shade on China. It's not a big voting block within the United States, it's not a big domestic constituency.

It's not to suggest that any of this criticism of China is insincere, but when it was Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, Mitt Romney was scolding China about currency manipulation, and Barack Obama was talking tough on human rights. We see this every four years, and then when it comes time to govern, the American president has harder compromises to make.

But one thing we also see every four years is that typically the winner of the contest for president runs on a campaign of doing less in the world. We saw this with George W. Bush, who wanted to stop nation-building; we saw this with Barack Obama as well, who wanted to do nation-building at home; we saw this with Donald Trump. And when these guys—and so far it has been guys—get into the White House, the imperatives of governing change, and there is a way in which there is a kind of difficulty in finding even foreign policy and national security talent that shares that particular worldview in Washington. For a number of reasons that changes, but this is to suggest that doing less in the world and the downsides of overextension are visible to the public, and there is a political reason, I think, why people succeed politically when they make the case to end endless wars, when they make the case to spend less on the military relatively even while maintaining military superiority and reprioritizing domestic issues.

So I hope we can talk about the political implications of this. We, like The Chicago Council, are a non-profit and non-partisan organization, so we don't give advice to any of the campaigns, but certainly our surveys have implications for the 2020 election.

NIKOLAS GVOSDEV: Thank you, Dina. Thank you, Mark. This was really great to give us a platform for taking the rest of the time to discuss.

I just wanted to complete the opening half-hour with a few points connecting to remarks that you both made with what we're finding from the Carnegie Council side and again some of these issues.

This point about foreign policy and domestic policy, which is that Americans will rank these domestic policy issues, but increasingly whether it's climate change, jobs, or the economy, they have foreign policy dimensions. I think we still do not always see the American public and also the campaigns making those connections as clear as they might be, that if you're going to pursue a particular strategy with regard to climate change, there's a foreign policy attached to it.

I was very struck by the reporting that Peter Beinart did earlier this month that these unity commissions between the Biden and Sanders campaigns to hash out how a Democratic Party platform will be created almost completely ignore foreign policy. There appears to be no appetite; it's all focusing on domestic issues, but leaving that question of the foreign policy implications of the domestic agenda that you're proposing as if these are two separate realms. I think that will be interesting to see.

From our survey results, which are not as broad as both of yours and also skew toward the people who responded to them, a couple of points I wanted to bring out: Most people have a sense that the world is getting more dangerous and not safer. This was done prior to the pandemic, but 8 in 10 said that they were expecting a major cataclysm of some sort, whether environmental or economic, to strike relatively soon. Maybe some people had a sense of foreboding already developing around COVID-19.

People were very split on this question of whether the default setting in world affairs now is one of competition or confrontation versus cooperation, with not quite a third and a third and a third but a 40-40 split on "We are in a competitive world/We're in a cooperative world" with the remainder falling into "No, this is a confrontational world." That has implications for what we have seen with the pandemic: Do you work with other countries to promote a common response? Do you safeguard or hold in things like vaccines because you want them for yourself and you feel that you don't want to give advantages to others? How that plays out will be interesting.

Two points that I wanted to throw in as well, which is the question of tradeoffs. When we have asked people about where the tradeoffs should be on certain issues we found responses all over the proverbial map. When do domestic issues take priority over foreign policy? When should foreign policy commitments take precedence over domestic issues? We found no agreement.

One of the more specific questions we asked was: "If disengagement from Afghanistan results in a settlement that sets back women's rights in Afghanistan, which do you take? Will you take disengagement from Afghanistan, an end to the military operation, or will you stay to try to continue to promote women's rights, gender equality?" There we found a split, often but not completely informed by the gender of the respondent. To some extent men were more willing to accept a peace deal in Afghanistan with less concern for how that might play out for women's rights, and women respondents not surprisingly were a little less eager to write off the fate of Afghan women. But again, these questions of how do you do the tradeoffs.

Finally, and I think this ties, Mark, to your last point about how this will play out—I'll finish here, and if, Dina or Mark, you have anything you want to respond to each other, and we are collecting questions right now as well, so I'll be quiet and let the questions come out to you—one of the things we asked at the end of our survey was, "If you agree with their domestic policy but you disagree with their foreign policy stands, will you vote for that candidate, either for presidential candidate or a congressional candidate?" What I was struck by was that two-thirds of the responds either said that they would vote for a candidate even if they disagreed with their foreign policy stance, or they weren't sure. Only a third of the respondents said, "If I disagree with a presidential or congressional candidate on foreign policy will I withhold my vote or cast for another." I think, Mark, that goes to your point about politicians and political appointees in Washington know that there is much greater grace that is extended to them on foreign policy issues should they go against the popular will than on domestic issues.

With that, let me turn it back over. Mark, Dina, if there is anything you wanted to respond to with each other, and then Alex Woodson will be presenting the questions as they come in.

DINA SMELTZ: I just wanted to go back to the China dimension, which I think will be a big issue. I think what's a little bit different now is that it has become much more clear that the two campaigns are trying to out-hawk each other now on China. In a way that was there during the primaries, but now it is even more, not only because coronavirus has made some Americans critical of China—perhaps some of them blame China for the outbreak. It's also what's going on in Hong Kong and Taiwan and everything coming together in a perfect storm that China might rise as more of an issue of resonance to both parties at this point.

I too, Nick, was taken by Peter Beinart's article. I thought that was interesting because I think it highlighted that Joe Biden's probable natural impulse is to be a restorationist. I think Tom Wright wrote about this too. He is focusing on undoing a lot of what Trump is doing and reaffirming the value of alliances and trying to restore the U.S. image in the world. But because he is also focused on getting the Sanders supporters to come into the Biden camp and because of the coronavirus issue highlighting domestic needs, foreign policy has not become much of a talking point for the campaign.

Like you, I do think that foreign policy is one way that Democrats can really stand out in a more simple way than perhaps in the past, not just to contrast the way the United States works with other countries, but that we should be positive toward our allies and not treat them disrespectfully and embrace dictators like Kim Jung-un and Vladimir Putin while at the same dissing our allies.

I think the American public's image of who a commander-in-chief should be for this country and what kind of person they would want, it seems like perhaps a case could be made that foreign policy really affects the way people around the world view the country and want to interact with it and invest in it. It seems like that could be the case, but foreign policy generally is not the top reason people vote, so tying it to other issues, especially those issues that have an international and domestic component—like immigration, like climate change, like jobs, the economy—would probably be a good idea.

MARK HANNAH: To Dina's point, she mentioned foreign policy is the way we're typically viewed in the world—and that is actually the subject of another survey that we at the Eurasia Group Foundation did more recently. We surveyed ten countries and their foreign publics to see what are the main drivers of their support or opposition to American-style democracy, to the United States in general, the favorability of the United States, and one thing that we realized, we ran a regression and found that if you resent American foreign policy, you're a lot more likely to have an unfavorable view of the United States than if you have other things about the American government or the United States that you dislike. That is a big driver of our perception overseas.

I do think, yes—also tapping in on the Beinart piece and the way in which to your point, Nick, that people might vote for a candidate even if they dislike their foreign policy because it might not affect their daily lives in a way that other issues might—the way that this could become a foreign policy election is when Americans realize that we're in this moment of an imperial presidency and the executive has a lot more leeway and a lot more latitude in doing certain things in the world than they do domestically. Domestically they're restrained in ways that they aren't necessarily overseas. So if people want a more stable or more predictable or more belligerent or restrained foreign policy, they might pick the candidate that fits that image and that vision, and it might have more sway this time around.

ALEX WOODSON: We'll go to a question from Nancy Stafford—Dina, you touched on this a little bit: "With the current China-bashing, how do you feel the situation in Hong Kong might affect the 2020 election? It would be uncharacteristic of the president to take on a rule-of-law issue, but he has been talking tough."

DINA SMELTZ: Yes, I touched on it. I think it will affect people's opinions about China. I think both candidates have less daylight between them in terms of dealing with Hong Kong and human rights issues. It would affect their opinions of China, I don't know if it would make somebody switch from one candidate to another, at least at this point.

Mark, what do you think?

MARK HANNAH: That's my read of it too. There was some cryptic language that Donald Trump uttered I think yesterday when he was asked whether he would put sanctions on China in response to crackdowns on these most recent protests. He said something like, "We're going to do something very powerfully, and you'll be surprised."

It's difficult. I think there is a tendency for both candidates to want to talk tough on China with respect to Hong Kong, and for all the commentary about how we're going to stand up with Hong Kongers, there is very little specificity in what the policy could or would be, and I don't think there is that much difference in how each responds to China.

I think Dina said it perfectly, that they are trying to "out-hawk" each other. The political imperative right now for both candidates is not to seem somehow weaker on China. Whereas Donald Trump might be reticent around issues of law and order with powerful strongman leaders like President Xi, he might ratchet up his rhetoric just not to be outdone by Joe Biden.

NIKOLAS GVOSDEV: I just saw on the chat from Nancy Stafford coming in that the State Department has just declared that Hong Kong is no longer considered "autonomous," so I think we're revising our position on that.

MARK HANNAH: And that is going to be a huge detriment, not only to Hong Kong but to the People's Republic of China and the Chinese Communist Party because that is a cash cow for them. While they're focused on unity, they also want Hong Kong to maintain its affluence.

Getting back to our survey results, we sacrificed some concision for precision, so we primed our survey respondents by saying: "China is getting more powerful. Its geopolitical influence is increasing. What do you think the United States should do specifically?" And we offered: "The United States should reduce its military presence while transitioning regional allies toward defending themselves and taking over responsibility for security." The other option was: "The United States should move more troops onto U.S. bases in allied countries, such as South Korea and Japan, and to increase its naval presence in the Pacific Ocean as well."

About 60 percent wanted to reduce our presence, only 40 percent wanted to increase our presence. And that was more pronounced among Independents and Democrats wanting to reduce our presence.

I did notice also in The Chicago Council survey that the perception of China as a "critical threat" in the past year—at least in 2019—was pretty much on par with what it has been throughout the past 20 years, and a lot less than it was in 1998 and 2002. So maybe that is going to go up this year as a result of this rhetorical escalation. I would be curious to know what Dina anticipates for the next survey.

DINA SMELTZ: Thanks, Mark, for taking that up.

I think we need some more questions. China is not considered a great military threat by Americans, but they're looking at it through the lens of a military threat to the United States. If we asked about a military threat to its neighbors or in the region, that might be something different. Again, whether they feel like that is a vital interest to them, Americans, is another question. So I think we need to dig a little deeper.

Certainly human rights issues are important but not as important as a lot of other issues, at least in terms of ranking in our surveys. They think preventing terrorism, right now combating infectious diseases like coronavirus is a very high threat for them. Defending and promoting human rights around the world is important, but it's not at the top of their agenda.

We will need to ask some specific questions, I think, about Hong Kong in particular and ask whether China is a threat in various parts of the world and whether the United States should do anything about it. Americans are very open to taking diplomatic and economic sanctions against a country. They're very supportive of exhausting all those. It's when more difficult matters come. Also, you would have to put tradeoffs in if there are economic sanctions that do something with our trade. We know that tariffs were hurting certain people more than others.

There are a lot of dimensions to it, and we need to do more. In general, Americans are more supportive of cooperating with China than trying to contain China or contain its influence. Given the past year, it should be an interesting issue for us to look at.

ALEX WOODSON: This is from Jonathan Gage: "Did any of your polls or surveys indicate that many Americans are concerned with the U.S. abdication of its international leadership role or with the widespread foreign perception that American leadership is in steep decline?"

DINA SMELTZ: Our polling shows that, in general, Americans still think we're the most influential country in the world. They don't see our influence declining now, but they do in the future. They see China's influence rising.

A lot of it comes down to partisanship. Republicans think this administration is doing a good job on all fronts—not all fronts, but for the most part Republicans tend to be supportive of the policies of this administration and think the United States is doing very well, while Democrats are the opposite and are not satisfied. I think this is a very partisan view right now. The partisan preference is super-important and a strong factor in how people view the United States right now. But in general, people still think of our influence as being intact.

MARK HANNAH: I don't have a specific question to whether Americans are upset about "abdication" of global leadership, but I will say that one thing we did look at empirically is whether people think we're an exceptional country and why or not. The amount of respondents who think we're not an exceptional country but simply that every country has attributes which distinguish it and ultimately acts rather in its own interests went up from basically a third to two-fifths between 2018 and 2019, and this rise was most pronounced among younger Americans. It was the top answer choice for respondents under 45 years old, and 55 percent of people between 18 and 29 think the United States is not an exceptional country. How much of that is related to pessimism connected to the current administration or how much of that is just young people not living through the heady successes of the Cold War is an open question.

DINA SMELTZ: I think it's the latter actually. We have a question too that we have asked for several years now, "Is the United States the greatest country in the world or is it no greater than other countries?" It has been going down. The first time we asked it—I can't remember what year, maybe 2014—it was like at 70 percent, now it's 60 percent.

Younger Americans have consistently been least likely to say this is the greatest country, and I think part of that is just growing up in globalization too, you know a lot more about other countries as well, and perhaps—

MARK HANNAH: Well, come on. It was also the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, these unsuccessful—

DINA SMELTZ: That's part of it too. But also I think, my generation was socialized in school to have this patriotic feeling about "You're so lucky to be born in this country; it's the freest country on earth." I don't know that that is the same way younger generations are socialized.

MARK HANNAH: Bring back civics education, right? I'm serious.

DINA SMELTZ: That might help.

I don't necessarily think it's a bad thing. Knowing that there are other great nations on earth and that for different reasons different countries are better at some things than others I think is healthy. Nevertheless, we do have that same finding in our data.

I saw a question about climate change, and I wanted to jump on that because that's one of my favorite items.

ALEX WOODSON: This is from Trina Thorbjornsen: "Does framing the climate crisis as a national security emergency significantly change voter attitudes when deciding whether they support a presidential candidate's foreign policy? I'm curious to see what the polling shows when intersecting climate and foreign policy."

DINA SMELTZ: If you frame any issue with certain wording, it will have an impact on people's views. Saying that it's a "crisis" and then asking people how they feel about it will impact their views.

We asked about a series of threats. Climate change was one of maybe 15 threats. It came at about the middle in our survey last year, but it was the first time a majority said that climate change was a critical threat to the United States, 54 percent. That has been inching upward, but that was great. It is especially high among Democrats, it's especially high among younger Americans.

Pew also asked the question a few months ago, and they found 60 percent rated climate change a threat, which is again below things like Iran's nuclear threat, North Korea's nuclear threat, terrorism, coronavirus and diseases like that, and nuclear proliferation. Those are often and always in the top five, but climate change is a growing threat, and again especially among Democrats and younger people.

MARK HANNAH: I think one thing the coronavirus has done is to demonstrate how the biggest threats to American national security are not national threats. The pandemic is an example of that as is climate change, so I think the way in which international cooperation is required in order to combat some of the more, if not existential, but the most dire threats to human lives and prosperity in the United States has been brought into stark relief in the past couple of months.

DINA SMELTZ: Climate change is also an interesting issue politically speaking because several Republican political campaign strategists—Frank Luntz, for example—are embracing climate change as a key issue for younger voters and that for the Republican Party to be able to grow their base among this new generation they should start addressing the issue. Also, there are economic implications that they can build a green economy around and make that a talking point.

It's interesting. We saw a tiny shift among the Republican electorate toward thinking climate change is a threat, but in certain states there are key individuals in the Republican Party who are also looking at that as an issue for the future.

NIKOLAS GVOSDEV: Dina and Mark, if I can, given some of the discussions that are happening on the chat simultaneously, I think in your last answer—if I can maybe ask you and Mark, the sense that demographic change in the United States, generational change in the United States, what impact does this have then on foreign policy? I'm not doing justice to the many questions that are coming through that I don't think we're going to be able to get to immediately, but there is a sense that a younger, more diverse group of politicians may have a different set of foreign policy priorities.

On the other hand, when I read Stacey Abrams' piece in Foreign Affairs, what really struck me was how conventional it was, that people will say you have to have new constituencies represented in the United States, but then somehow people go into a box and they come out as committed Cold Warrior trans-Atlantacists, saying the same thing that would have been said 30 years ago. Is there any sense that you're getting from the polling data or anything else whether we should expect that Millennials, Gen Z, as they start to move up in politics, will lead to changes in how we conceive of foreign policy and national security?

DINA SMELTZ: Your last point, Nick, reminded me of two things. After the 2016 election, people were really interested in the views of the Midwestern public—especially with us being in Chicago—and said: "Well, what happened in the Midwest with the election? Midwesterners must really want to put their heads in the sand and not deal with the outside world."

We did a booster sample, which is an expanded sample, in the Midwest that we could then compare with more confidence to the other parts, and we found very little. There was a little bit of difference on trade, Midwesterners were more concerned about the tariffs against China having an impact on them, which was a bit prescient. But other than that, there weren't very many differences.

We did another study years prior and looked at Latino Americans and did another expanded sample of them and found that among Hispanic Americans they had the same foreign policy as all other Americans except they had a greater confidence in the United Nations and seemed more familiar with the United Nations and were more concerned about climate change than the average American at that time.

There are some key constants across Americans that want to work with other countries in the world and that they want to be engaged in the world. There are demographic trends that would suggest that perhaps more Democratic leaders would be favored if the current trends continue, just that people who are non-white and younger tend to be more liberal than older and white Americans.

The younger people—and Democrats too actually—emphasize less America's projection of its strength and influence in a military way around the world. That includes defense spending. It also includes getting involved militarily in entanglements abroad. They support peacekeeping. It doesn't mean they don't support coming to the aid of allies if they're threatened, but in general, especially younger Americans right now are less supportive of military interventions.

Part of that could be the life cycle they're in because we do see a trend toward being more accepting of that as people age, but there is something—at least in the last surveys we did among the Millennial generation—that they are a bit lower in terms of tolerating military interventions. We will see, but those would be the main things in terms of foreign policy. I don't think there are any great cracks in whether we should follow a multilateral type of approach compared to today.

MARK HANNAH: I agree with Dina. Anybody who hasn't checked out The Chicago Council's study on intergenerational differences, I highly recommend it to them. It's a wonderful and insightful study on the way in which—to the conversation earlier—the younger generation, which has not lived through the Cold War success let alone World War II and the Greatest Generation victories, is a lot less bullish about intervention.

One thing that we found from our study that corresponds with this is that we proposed a scenario with military intervention in the case of human rights abuses, and we were surprised to note that the youngest generation—people 18 to 29—were more likely than other age group to effectively abstain from intervention in the case of human rights abuses.

This is a generation that is seen as somehow invincible—we think of young people as invincible and empathetic toward foreign populations—and this is the group that effectively wanted to focus on human rights problems at home more, such as mass incarceration and aggressive policing. Rather than going abroad it wanted to focus on other things. The only group that supported intervention over non-intervention was 60 years old and over. So I think we are seeing a way in which the younger generation is coming up with a different set of lived experiences than the older generation, and that is shaping their policy preferences.

It's also happening in the economic sphere. They're not anticipating being economically better off than their parents, and so there is a lot of talk and scholarly discussion about how they're down on free market economics compared to other generations. So I think there is a way in which experience informs preference, and we're seeing that in the foreign policy sphere, no doubt.

DINA SMELTZ: Everyone looks at the Millennial generation as the generation that has broken with the trends, but in our data it is actually consistently the 45-and-overs who are different from all the younger generations, and I think that's the Cold War experience and experiencing military interventions that we may see as having been successful, whereas Afghanistan and Iraq are not necessarily seen as being successful in their missions. I think that might have a big influence on whether you think these interventions are worth it or not—and also how long they have been in play.

NIKOLAS GVOSDEV: That's a great point.

We are at the top of the hour, so we are going to close this discussion.

I want to thank everyone for their contribution, certainly Mark and Dina, and all of our participants. We have tried to put onto the chat many links to things you have heard referenced today—articles, reports, studies—so that you can continue to look at these things. This will be posted to YouTube as well, so feel free to circulate it to people who were not able to attend and continue the conversation there.

Certainly, also please take the opportunity to see what future events and studies and reports will be from the Carnegie Council but also from The Chicago Council and the Eurasia Group Foundation so that we can continue these conversations in future settings.

Again, thank you to my guests and panelists on this. With that, we will call this meeting to a close.

MARK HANNAH: Thank you, Nick. Thank you, Dina.

DINA SMELTZ: Thank you. Great to see you.

MARK HANNAH: Likewise.