In the second podcast in The Crack-Up series, which looks at how 1919 shaped the modern world, historian Ted Widmer talks to Harvard's Professor Lisa McGirr about Prohibition's roots in anti-immigrant sentiment and its enforcement, in some cases, by the Ku Klux Klan. Plus, they discuss the Eighteenth Amendment's connections to World War I and the rise of the modern American state.

TED WIDMER: This is Ted Widmer, and you're listening to another episode of The Crack-Up, and we are very lucky to have Lisa McGirr, a professor at Harvard University, with us today. She has just written a piece in The New York Times about Prohibition and the Eighteenth Amendment.

Welcome, Lisa.

LISA McGIRR: Thank you so much for having me, Ted.

TED WIDMER: Can you tell us a little bit about the story that appeared a couple of days ago?

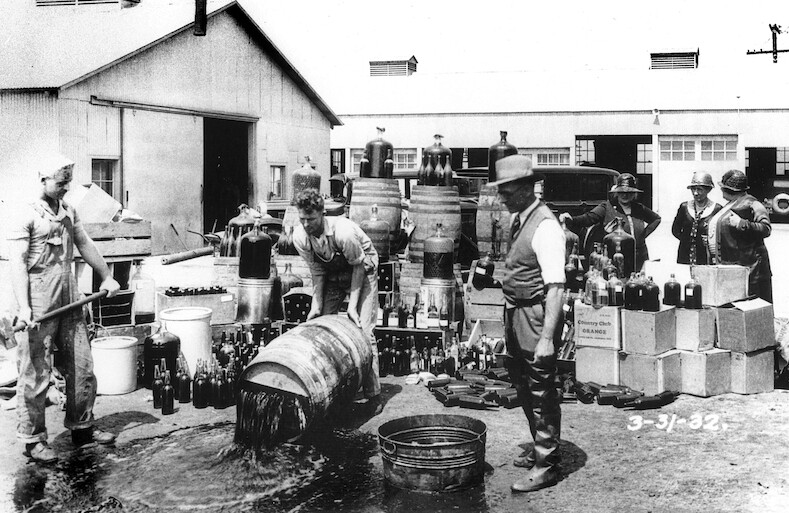

LISA McGIRR: The story that appeared a couple of days ago basically revisits Prohibition at the moment of its 100th anniversary of ratification. Prohibition was first ratified on January 16, 1919, when Nebraska was the 36th state to ratify, and that essentially ushered in Prohibition, which was to go into effect one year later, on January 17, 1920. Basically, the article uses the opportunity of the anniversary to look back and analyze some of the ways in which the moment that we're living in today has certain resemblances to the Prohibition era and to chart out many of the legacies of Prohibition that we know less about.

In popular memory we think of Prohibition in terms of bootleggers, moonshiners, bathtub gin, speakeasies, and we think less about some of the very significant long-term legacies and consequences, and those are the things that I try to chart out a bit in the article for The New York Times.

TED WIDMER: There's so much I realized I did not know about Prohibition as I read your piece. The first thing I didn't know is that it really was targeting immigrants and foreigners. Where did that come from?

LISA McGIRR: Prohibition came out of a very, very long campaign. Temperance and prohibition sentiment had a long history going back to the late 19th century. But the movement essentially changed from one that had focused on reining in and disciplining one's own drinking—taking a pledge, agreeing to be abstinent—to targeting the drinking of others, and that came about with this massive wave of immigration in the early 20th century.

So white Protestant men and women in the early 20th century were anxious about a lot of social changes, one of the big ones being this massive wave of immigration. Between 1880 and 1920 there were about 20 million immigrants that came to the country. The wave peaked in the early 20th century, at the same moment—from 1907 and around those years—that Prohibition really took off in terms of a national campaign for a constitutional amendment.

The white Protestant men and women who had long embraced a kind of temperance ethos as pretty central to their self-identity identified working-class immigrants drinking in the saloon as a threat to an older American way of life. The saloon congealed a whole host of anxieties that they had about immigration, about urbanization, and about the social changes that were taking place, demographic change, in the early 20th century. That's how it links to a kind of anti-immigrant sentiment.

TED WIDMER: You make clear how large the scale of immigration was. Most of us aren't about to defend Prohibition, and yet the change was profound. As you say, a million immigrants in 1907. So there was legitimacy to feel that the country was changing very, very fast.

LISA McGIRR: The country was changing very fast. Cities were changing rapidly. There were growing numbers of saloons in the big metropolitan places like New York, Chicago, and elsewhere.

The reality is that Prohibition tried to grapple with the very real social problem of excessive drink. It just far overshot the ills it was intended to cure, and it did so in a way that really targeted the drinking of particularly immigrants in these saloons. That's how it gained its energy and how it succeeded in passing, by building a coalition around this anti-saloon sentiment.

TED WIDMER: At the end of your piece you make all these startling counterintuitive claims that basically everything backfired, that these were people who did not want a huge state. They didn't want the government intruding into everyone's personal lives, and yet that is more or less what happened because of the rise of the penal state.

LISA McGIRR: Yes. I think that is something which—there were a number of folks who were traditionally skeptical of the state. For example, the South actually led the way in state prohibition laws, and the South is very well-known for being anti-federal power and skeptical or suspicious of government authority.

At the same time, though, I think one had to be careful because there were also a lot of Progressive men and women who came onboard in favor of Prohibition, and they were less skeptical. They wanted to utilize the state to promote what they saw as social betterment, and that constitutional amendment in some ways was in line with a whole series of constitutional amendments that were passed, including the direct election of senators and the income tax, around the same time.

I think it's important to note that there were those who were both skeptical and who it actually backfired for, that in fact they increased state power in ways that would have surprised them, especially since once you have a growth in federal authority it's not so easy to rein in, and the New Deal took it in many different directions that these men and women might not have wanted to. But there were also I think men and women who were not so opposed to using the state, who saw Prohibition in line with their efforts to use the state to promote social and economic betterment.

TED WIDMER: That's so interesting. So it's a complex coalition with some Progressives and then a lot of people who were pretty evangelical or definitely small-town American.

LISA McGIRR: Exactly.

TED WIDMER: Yes, that's fascinating.

Can you tell us how World War I sped up the—

LISA McGIRR: Absolutely. Right before the war there was a lot of building sentiment in support of Prohibition because there are again anxieties over immigration; there are a number of states that pass prohibition laws. There is building sentiment, and Congress does pass legislation which is basically the same kind of language that becomes the 18th Amendment, but not with the two-thirds necessary to send it to the states, by far not.

So it takes the war essentially to help put Prohibition over the top. What happens and why is that I think in wartime you have a focus on national efficiency. The idea of using wheat and hops for beer and other things becomes less acceptable.

You have a growth in government power more broadly. If the government's taking over the railroads, then suddenly banning the liquor trade and having the government enforce that ban seems less out of line with other forms of state building.

You also had the prohibitionists themselves using the example of Europe. Of course, the United States entered the war much later than Europe. The war started in 1914 in Europe, and many European countries instituted partial prohibition bans or different kinds of limits on their soldiers drinking or limiting pub hours or banning certain kinds of hard liquor, never undertaking the kind of absolutist approach the United States did when it instituted Prohibition, but the prohibitionists themselves, the anti-liquor crusaders, pointed to those regulations and said: "Hey! Now we're even behind Europe."

So between 1914 and 1917, when the United States entered the war, there is already increasing support for Prohibition, and by the time the United States enters the war the call for wartime efficiency and in particular, of course, the hostility toward all things German—since we were fighting against Germany, and many of the breweries were in German hands—it became very easy to identify and to scapegoat those liquor producers as enemies of the American state and to argue that in fact Prohibition was the most patriotic act. I think that is really what helps to put Prohibition so rapidly and quickly over the top.

TED WIDMER: It's funny because you think of Budweiser beer as this great sort of icon of American culture, and yet 100 years ago it was basically the opposite.

LISA McGIRR: Right. Also suggesting the way our targets shift. Now ethnic white Americans—Italians, Poles—are very much part of the body politic, but in those years these were the main targets in groups like the Klan—Catholics, Poles, Czechs. Folks who are very much enfranchised Americans today were those who were thought of as outsiders and threats to the American Republic.

TED WIDMER: Didn't Budweiser rename itself "America" briefly? There was a kind of America beer you could get that was actually a Budweiser, but they slapped the word on the can?

LISA McGIRR: Probably, yes. Not surprisingly.

TED WIDMER: You just mentioned the Klan, and that is fascinating in your piece because most of us know the Klan for its racial hostility to African Americans, but in your piece it's a different Klan. It's quite active in the Midwest, it's targeting immigrants really more than anyone else, and very worked up over Prohibition and liquor. Can you tell us about this version of the Klan?

LISA McGIRR: Sure. The Ku Klux Klan as you know was first established during Reconstruction. Its strength was overwhelmingly in the South, and it targeted African Americans and identified itself absolutely as a white supremacist organization, white Protestant, of course, but white supremacist above all.

This second Ku Klux Klan was established in Stone Mountain in Georgia. The inspiration for its revival came from the film The Birth of a Nation, which was originally titled The Klansman, which glorified the activities of the Reconstruction-era Klan. So it had links to that older Klan. It still identified itself very much as a white Protestant organization.

That was in 1915. But the Klan really only took off after 1920. It did have pockets of strength in the South, but where it really snowballed and gained an enormous amount of strength that it never had before was in places like Indiana, Ohio, and parts of the West, where there was an intersection between white Protestantism and temperance and new anxieties not just about white supremacy but about the survival of this white Anglo-Saxon Protestant ethos against the threats they perceived of as coming from this massive wave of new immigrants, who also happened to be largely Catholic.

So the Klan by 1920 was motored by anxieties that came out of the war, partly African Americans' new militancy, veterans returning home wanting new rights, norms and changes that came from the war, but most importantly the Volstead Act or the Prohibition law. The Eighteenth Amendment and then the Volstead Act provided the Klan a new opportunity to sell itself to white Protestant evangelicals, who had anxieties over all sorts of social change, as an organization that would stand up for 100 percent Americanism, in other words, target these enemies of 100 percent Americanism, by reining in drinking. So they used the opportunity of this war on alcohol to basically target immigrants and Catholics, those whose drinking they conceived of as a threat to the nation.

It's not that the Klan itself was a temperance organization. Many men and women were evangelical white Protestants. The Klan was not unknown to drink. In Colorado Springs, Colorado, there was one example where the Klan in fact utilized its strength to become the primary driver of a bootlegging ring by the vigilante targeting of others.

But for the most part, evangelical Protestants identified drinking as the devil's drink, as did their ministers, and even if they failed and fell into the sin, they saw the law as a way to rein in the drinking of others, and that's the intersection, a connection between the Ku Klux Klan and the Volstead Act.

So essentially, all those white Protestant evangelical men and women who had worked so hard to gain the law's passage and who really wanted to see it succeed, all those anxieties that they had coming out of the war only increased during the 1920s because partly Prohibition itself drove a counter-rebellion against this kind of coercive crusade.

Of course, as much as there was a huge ratcheting up of government muscle to try to rein in violations and to make the law a success, the federal government was puny. It was growing, but it was too small to undertake this incredibly ambitious and almost impossible-to-meet goal of eradicating drink from shore to shore. Therefore, the Klan basically made an argument that it would step in: "If your local police, if your Prohibition agents aren't going to do their job, we can clean up your community. We will clean up those moonshiners and bootleggers." At the local level, they frequently recruited through the drives of anti-bootlegging campaigns, through cleaning up the communities, and when they did so, then of course they also often targeted the drinking and launched crusades, sometimes linking up with police forces, but in other places where the police weren't doing their job, they would basically be sometimes in battle with these police forces in order to enforce the law.

TED WIDMER: How do you research on the Klan? They were secretive in their day. I'm sure they concealed a lot of records. Where do you go to do historical research?

LISA McGIRR: There is a number of places. There are a lot of newspaper articles. For example, the story that I tell on Williamson County, Illinois, where the Klan launched a set of anti-liquor crusades which were quite violent and sparked a kind of terror campaign against local immigrants that drove out many immigrants from the community, you just have to go to both local newspaper sources, and this was in Williamson County, Illinois, so Chicago newspaper sources had a lot of this. You can look at enforcement records where they talk about actually Klan involvement in some of these anti-liquor raids.

The Klan is a hard organization if you want to look at the internal dynamics and to get membership records because it was secretive. There are archives, like in Athens, Georgia, there are some Klan records that Nancy MacLean used in her book.

Kathleen Blee did a great job in getting access to not just Klan records but charting out memberships in Indiana and seeing connections between the Klan and the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). If you do this kind of local groundwork on different places, it's possible to get to these connections and intersections.

The Klan was not as secretive as the Klan then became. It called itself a secret membership organization, but its leaders were pretty out there. It was known that these were Klansmen. They were marching in the street, often in their regalia, and so they were not a hidden organization in that sense.

TED WIDMER: You mention a women's auxiliary of the Klan. I didn't know about that. Also, with the Women's Christian Temperance Union, women are pretty strong in the story, but I think most of us today would say they were on the wrong side of history, and yet maybe in some ways this was fulfilling for women who were denied a lot of political power, but in this movement they were very strong.

LISA McGIRR: It's important to note that women could not be members of the Ku Klux Klan. It was an all-male, all-Protestant, patriarchal organization. But yes, they could join and did join and formed the Women of the Ku Klux Klan, precisely to provide helpmates to their white Protestant men in upholding the values of white Protestant evangelicalism.

Were they on the wrong side of history? In terms of Prohibition, women were all over the place. They were members of the Klan in places like Indiana and Ohio. They were also bootlegging queens in New York and Prohibition opposition, people like Pauline Sabin. So I think women were not on one side of this battle, but there is a linkage I think between gender and temperance sentiment, and that's what explains, of course, the Women's Christian Temperance Union, this huge grassroots organization, because excessive drinking was seen as doing particular harms to women and children given the fact that women were dependent on the male wage at that time.

As a result, if a man stopped in a saloon on his way home from work, drank excessively, it made them more prone to domestic violence. This is actually a real issue.

TED WIDMER: Right.

LISA McGIRR: The way the white Protestant middle class chose to solve that issue was not necessarily the same way that immigrant women would have chosen to solve that problem, but they were addressing a real issue of concern, also to working-class immigrant women.

TED WIDMER: One of the best parts of your piece is when you explain statistics and how then as now it's pretty easy to come up with false statistics about immigrants.

LISA McGIRR: Right. It's easy now, and it was probably even easier then, in part because crime statistics were very much in their infancy. But prohibitionists, anti-liquor crusaders, came up with numbers really out of the air. For example, the Indiana WCTU declared that 75 percent of liquor law violators were foreigners at one point.

The reality was that the work that was done, the studies that were done in the latter part of the decade by social scientists, by Edith Abbott, for example, showed in a study called Report on Crime and the Foreign Born, that in fact the foreign-born were less likely to be arrested for all sorts of crimes, including Volstead violations, and that it was in fact those who were born here—

TED WIDMER: Just like today, right.

LISA McGIRR: —who were more likely. But this was one way of again using scapegoating or scare-mongering tactics to target foreigners and immigrants to this country.

TED WIDMER: Can you tell us about the end of Prohibition and how basically it drove people to form new political alliances? Just like it was a complex alliance, it created ones on the other side that basically defeated it. Can you tell us that story?

LISA McGIRR: That's a really interesting piece of the story, and one of the ways that you mentioned, this idea that Prohibition backfired against those who were its most ardent supporters.

In the end, the opposition to Prohibition led all of these ethnic immigrants, whether they be Bohemian or Polish or German or Italian, to a new sense of identity that was less locally identified and more nationally, started to think of themselves more as Americans who were entitled to their rights.

TED WIDMER: Fascinating.

LISA McGIRR: Essentially, the opposition to Prohibition, the sense of grievance that it pushed, both the very, very real grievances that they experienced in terms of the actual targeting by groups like the Klan, but also the symbolic sense of Prohibition as an attack on their communities, and a real attack, of course, on their culture and leisure habits because many new European immigrants, whether Italians with their wine culture or Germans with their beer culture and beer gardens, it was a real kind of attack on their culture and leisure habits.

As a result—and it's also the case that because immigrants were largely poor just like African Americans and Mexican Americans, the illicit industry, the sort of new criminal gangs that were established and flourished in order to supply Americans with bootleg liquor often found their places of production within immigrant neighborhoods, so places like Chicago, for example, Al Capone and Cicero. These are immigrant neighborhoods, and these are the places where organized criminal rings really take root and flourish, partly because the police are willing to look the other way in these poor neighborhoods. As a result, these neighborhoods are the ones that are more subject to the violence of Prohibition and when there are crackdowns more subject to those crackdowns.

There are all sorts of really negative effects of the law, not to mention, of course, the fact that if one did choose to drink, for poor people it was a lot more expensive, the quality was really poor, there was sometimes poisonous liquor, and all of that meant that Prohibition was a serious grievance, which I think is something that after 100 years we have failed to really understand.

If you look at the ground level, if you really penetrate these ethnic immigrant communities, if you look at their newspapers, you can see the extent to which they were incredibly angry and upset, and the way that they began to mobilize not only in local politics but at the national level. Their opportunity really to do so comes in 1928 when the governor of New York, Al Smith, decides to run for the presidency. He was an Irish Catholic himself. He was absolutely opposed to Prohibition. He also championed tolerance. He spoke out against the Klan. He drew these new immigrant men and women in droves into the Democratic Party for the first time.

Prior to 1928 immigrant men and women's political identities were brokered through a local ethnic ward boss. Whether you were Republican or Democrat depended on what your ethnic ward boss essentially said, how you should vote or how you were going to get a job you were going to choose a Republican or Democratic ticket. For example, in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, those places were heavily, basically totally dominated by the Republican Party. Even industrial working-class immigrants were fundamentally voting for the Republican ticket.

Basically, immigrants were divided, and it's really in 1928 that you get a realignment of working-class ethnic immigrants into the Democratic Party in large numbers and where they stay, of course, to help forge FDR's Democratic New Deal coalition in 1932 and 1936 and beyond.

TED WIDMER: If that logic holds 100 years later—I know it's not the same situation, and most immigrants today are probably more Democratic than Republican anyway, but still—what you're saying is a harsh repression usually leads to a backlash of some kind, so we might see some interesting political changes, maybe a bigger Democratic Party in a few years, but some aftereffect.

LISA McGIRR: I think we have already seen that effect in the midterm elections. We have a much more diverse Congress or House in particular than we've ever had before.

TED WIDMER: Right.

LISA McGIRR: We have immigrants really enfranchising themselves on a platform of tolerance, of pluralism, a sort of revivalism of fundamental values of the importance of immigration to this nation, to its history. I think that may unfold further so that this backlash force can in fact promote a counter-reaction or rebellion and a new sense of energy, of the importance of being part of politics, and I think that's part of it.

I think you're right that, for example, there are Hispanics who are also Republican, but there are a lot who are Democratic. But it doesn't mean people are necessarily energized to go to the voting booth.

TED WIDMER: That's right.

LISA McGIRR: And this is the kind of thing, this kind of powerful hostility can drive folks to really say their piece and become part of politics, and that's certainly what happened in 1928.

TED WIDMER: Lisa, I cannot thank you enough. What a wonderful, historically informed conversation.

Lisa McGirr is the author of The War on Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State and a fantastic article in The New York Times this week.

Thank you so much, Lisa.

LISA McGIRR: Thank you so much, Ted.