Daniil Davydoff is manager of global security intelligence at AT-RISK International and director of social media for the World Affairs Council of Palm Beach. Davydoff has been published by Foreign Policy as well as RealClearWorld, among other outlets. His views do not reflect those of his company.

Maritime incidents—the Lusitania, Pearl Harbor, the Gulf of Tonkin—heralded U.S. involvement in several 20th century conflicts. Today marks the anniversary of the start of one such conflict, the Spanish-American War, which followed the sinking of the USS Maine in 1898. Although the war took place nearly 120 years ago, it can serve as a lesson to our current administration. Like William McKinley, the president during the Spanish-American War, Donald Trump also faces a possible maritime crisis amidst public concern over the country's foreign policy passivity. However, Trump cannot afford to handle a crisis—this potential one in the South China Sea—or its aftermath in the same way that McKinley did.

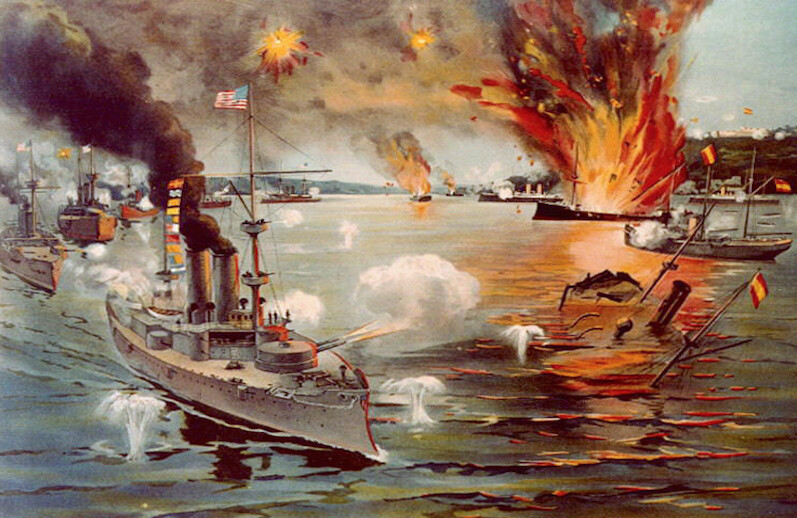

The Maine was sent to Cuba to defend U.S. interests following unrest in Havana in January, 1898. After the vessel exploded, the popular conclusion was that Spain was to blame, and both expansionist and humanitarian sentiment drove the U.S. to declare war in April. By July, Spain had surrendered and withdrawn from Cuba; the U.S. annexed the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. Although contemporaneous and present critics of the conflict have judged it a victory for American imperialism, and ramifications for the "freed" peoples were decidedly mixed, there is little doubt that the war was a strategic success for the U.S.

Islands are also at the core of the current South China Sea dispute. The Paracel and Spratly island chains, as well as Scarborough Shoal, are within a maritime territory of some 3.5 million square kilometers claimed by China. Despite contestation by the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Brunei, China has escalated the dispute in recent years by building and militarizing artificial islands in the area. With the U.S. seeking to prevent Chinese expansion and conducting patrols, tensions and the possibility of a miscalculation or confrontation are high.

Politically, the comparison between the two eras can be drawn out on the domestic and the international fronts. Like Trump, McKinley had an "America first" perspective on economic policy at home, with trade protection and growth of U.S. businesses a top priority. As with the Bernie Sanders movement, McKinley likewise had to contend with the competing populism of William Jennings Bryan during his presidential campaign.

Most importantly, on foreign policy, both men share a certain personal reluctance on international involvement coupled with a mandate—and high-level support—for forceful action in case of crisis. Just as the explosion of the USS Maine provided hawks in the McKinley administration with a justification for a military response to Spain, a crisis in the South China Sea today could prompt a comparable reaction from the new government. While no incident has yet encouraged use of force in the South China Sea, the April chemical attack in Syria and the U.S. government response highlights how quickly the administration may respond to perceived violations. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has already stated his support for a policy of strong responses to further Chinese construction and militarization of contested islands. Defense Secretary James Mattis and National Security Adviser H. R. McMaster, meanwhile, may play the role of the erudite Theodore Roosevelt, assistant secretary of the U.S. Navy when the Maine exploded, in pushing for a tough approach.

Due in part to Roosevelt, the U.S. Navy was well-prepared for the Spanish-American War. However, deficient planning and organization cost the U.S. ground forces dearly, with many historians placing the blame on Washington and Secretary of War Russell A. Alger. Many troops and most mounts never left Florida due to transportation constraints, supplies and armaments were inadequate, and the majority of U.S. soldiers perished after contracting tropical diseases that flourished in Cuba's rainy summer season. In this context, whether current officials fan the flames or a crisis comes about in some other way, the new administration needs to consider all the ways in which a poorly handled South China Sea crisis could have disastrous consequences.

To begin with, today's rising China is not yesterday's declining Spain; it has a formidable industrial base and military. There is no question that, at the very least, U.S. casualties could easily surpass the Spanish-American War's approximately 3,000 in almost any conflict scenario. Another Battle of Manila Bay, where the Spanish Pacific squadron was destroyed at the cost of one American life, is highly unlikely. Seeing as numerous population centers surround the sea and the waterways are a key transport channel, civilian casualties could also mount up quickly.

China would have several other advantages, including the "home court" advantage that Spain never had, should conflict break out. Furthermore, the proximity and strategic importance of the theater to China would also mean that the country has a great deal more at stake than Spain did in Cuba. The U.S. maintains the best naval fleet in the world, but China's cyber capabilities could even out the playing field by disabling or even taking control of critical technology aboard U.S. vessels. As yet an untested strategy in battle, high-profile private and state-sponsored hacks have already shown the power of asymmetric cyber warfare in the political and commercial realms.

Finally, China's other major asymmetric advantage is its control of production of more than 85 percent of the world's rare earth minerals. Considering how much modern technology, including military technology, is reliant on these materials, America's dependency on Chinese imports is dangerous. Both the public and private sectors are trying to diversify sources of supply and find substitutes, but a 2017 report by the U.S. Geological Survey notes that the U.S. is 100 percent import-reliant on as many as 20 rare earth minerals and China is the main source of imports. Such minerals are used in production of missile guidance systems, night-vision goggles, and communications devices, among other equipment. As such, U.S. planners would have to make the most of the reserves or resort to outdated technology should supplies from China be cut off for an extended period.

The lesson to glean from these differences is a simple one: A very specific set of circumstances allowed the U.S. to achieve its military aims in the Spanish-American War despite serious failures in planning. Anything less than a well-thought-out strategy cannot achieve the same results today and could result in significant loss of life, military and civilian, should China cross a red line established by the new administration. Perhaps more on this issue than on any other, Trump and his cabinet need to have a consistent game plan. They must consider the guidance of diplomatic, military, and intelligence experts, even if the overall approach is dictated by administration objectives.