The fight for human rights is losing. Ranging from the broken humanitarian response to the Syrian refugee crisis, to the rise of the far-right across the United States and Western countries, to the increased targeting of environmentalists in Latin America and Southeast Asia, human rights violations are becoming white noise and fail to grab the attention of the international community. At the same time, the international community has yet to challenge its understanding of how human rights look in the age of climate change and increasing interconnectedness. In particular, many of the voices that are currently being raised in protest are advocating for the protection of collective rights—for the rights of indigenous peoples; communities of color; of women; of the LGBTQIA+ community, or for rights that can only be claimed collectively, like the right to a healthy environment or the right to self-determination.

For these reasons, this article calls for a change in focus: it is time for the world to move away from liberal and neoliberal-centric understandings of human rights that underline the importance of the individual, and recognize instead the importance of emphasizing a collective human rights regime. Such recognition may be the only solution to our present malaise and the path toward an improved global solidarity.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the most widely accepted human rights statute in the world, was drafted in response to the realization that governments do not always have the protection of their citizens in mind. After all, the Holocaust, colonialism, and the atrocities committed during the Second World War catalyzed the international community into asserting that all humans are born with basic rights. Moreover, the adoption of liberal human rights theory by the West has resulted in this idea that the rights of the individual supersede the rights of the collective. For example, in 1995, when the United States rejected a draft declaration on collective Indigenous rights, it issued the following statement:

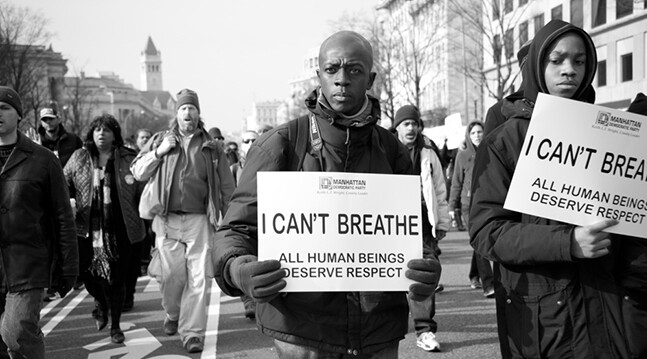

International instruments generally speak of individual not collective rights. ... Making clear that the rights guaranteed are those of individuals prevents governments or groups of (sic) violating or interfering with them in the name of the greater good of a group or a state ... In certain cases, it is entirely appropriate or necessary to refer to indigenous communities or groups, in order to reinforce their individual civil and political rights on the basis of full equality and nondiscrimination. But characterizing a right as belonging to a community, or collective, rather than an individual, can be and often is construed to limit the exercise of that right (since only a group can invoke it), and thus may open the door to the denial of the right to the individual. This approach is consistent with the general view of the U.S., as developed by its domestic experience, that the rights of all people are best assured when the rights of each person are effectively protected.In focusing solely on the individual, liberal human rights theory does not recognize collective cultural, socio-economic, or political narratives that groups of individuals share. An African American male in the United States may be granted due process as a human right under the U.S. Constitution. However, this does nothing legally to address that the justice system is biased against him based on the group to which he belongs.

Under neoliberalism, the value of the individual within free market competition is paramount. The growth of this neoliberal economic model, with its focus upon the competition that exists between individuals and groups rather than the cooperation that exists between them, has undermined the development of collective rights. The primacy of and lack of power held by the individual is therefore quintessential and any notion that such individuals function as a collective that would seek to claim rights as a collective entity has been seen as a challenge to such primacy. In his book, Taking Suffering Seriously: The Importance of Collective Human Rights (1996), international human rights expert William Felice stated,

Liberal human rights theory often does not recognize that equality of opportunity is an illusion in a society based upon competitive individualism, where not only is individual pitted against individual, but group is pitted against group. In such an atmosphere the rights of those groups of the lower end of the spectrum of opportunity must be protected, or all individual and group rights are diminished.Although Franco-Czech jurist, Karel Vasak, raised the flag for the need for collective rights, the Universal Declaration called for the protection of collectives of humans, and not solely the individual. However, there has yet to be any acknowledgement by the wider international community that groups of individuals deserve their own statute of rights. Today, this could not be more evident. What Vasak calls 'Third Generation Rights' are the rights needed for groups of individuals to flourish; that along with First Generation rights, or political and civil rights, and Second Generation rights, or socio-economic rights, there must be recognition of the sociability of humans and why the groups and communities that are created must not only survive but thrive. This is an important point to emphasize. Individual rights are not in competition with collective rights, and collective rights are not seeking to undermine those individual rights that currently exist. Rather collective rights recognize that protecting each individual is not enough. It is not enough when certain rights that such individuals claim are indivisible, including, as Vasak alluded to, a right to peace, to a healthy environment, to self-determination and to economic development.

Cultures around the world have recognized and have even prioritized the importance of the community over the individual, long before Vasak, the Universal Declaration, or the international community saw the need to articulate collective rights. Indigenous peoples particularly have spearheaded this and continue to fight for collective rights for themselves and for humanity. It is of no surprise then that the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples remains the only UN statute dedicated to collective rights. But perhaps nothing illustrates the importance of collective rights to contemporary society better than the present situation at the Standing Rock resistance camps in North Dakota. As the indigenous Standing Rock Sioux lead the mass protest aimed at blocking the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, the right to self-determination via indigenous sovereignty and the right to a healthy environment are the paramount issues being raised.

So much of what humans suffer—the impact of conflict, of climate change, marginalization and dispossession—they suffer together and thus recognizing the importance of collective rights also recognizes the fact that as human beings our responsibility is not only to ourselves but to others. Because collective rights are also solidarity rights. They say that people stand together in order to not only protect our rights today but the rights of those who will live tomorrow.