This speech was part of an August 18, 2010 event entitled "Is Peace Worth Fighting For? which was part of the Scottish Parliament's Festival of Politics. The other speaker was Sir Malcolm Rifkind QC MP and the event was chaired by The Very Reverend Graham Forbes, Provost of St Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh.

It is an honor to be here in Scotland, in this august chamber, to participate in this Festival. To convene a Festival of Politics—a Festival of Ideas—is an inspiring notion. Politics should be festive! The openness of these proceedings—the willingness to ask and answer the toughest questions of public life and to do so in a spirit of genuine inquiry and celebration—this is what democracy is all about.

You have already voted with your feet by making the time and effort to join us. I'm delighted to see that you are also being given the opportunity to vote on the ideas we'll be discussing. A conversation—and an election—is always more interesting when the outcome is in serious doubt. The doubt adds creative tension, doesn't it?

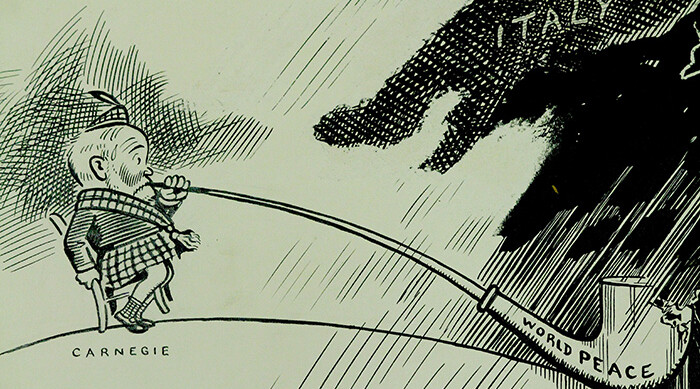

I would like to begin by thanking the sponsors of this event—and in particular the Carnegie-UK Trusts and its Chief Executive Martyn Evans, its President, Mr. William Thomson, and its Vice Chair, Mr. Angus Hogg, who have arranged extraordinary hospitality while I am in Scotland this week. This trip is a pilgrimage of sorts for me and two Carnegie Council Trustees who are here with us, Kathleen Cheek-Milby and Stephen Hibbard, as we connect with our Carnegie brothers and sisters here in Edinburgh and in Dunfermline.

My remarks today are inspired not only by this convening and my respect for my two distinguished co-panelists, but also by two additional Scottish gifts to the world of ideas. Those two gifts are the legacy of Mr. Andrew Carnegie and the ongoing Gifford Lectures in philosophy, which as many of you surely know, attract some of the world's greatest living philosophers to Scotland on an annual basis. Both Mr. Carnegie and the Lectures have been sources of creative thinking when it comes to the issue of ethics in war.

First, let's talk a bit about the legacy of Andrew Carnegie. Mr. Carnegie had his own answer for our question of the day, "Is Peace Worth Fighting For?" His answer would have been direct and clever. He would likely have said: "This is a false question. Peace does not require war." Carnegie believed that we have within our grasp the rational means to avoid war. War is a choice. And it's a choice that we should not have to make.

As many of you know, Mr. Carnegie enjoyed a celebrity reputation much like that of Bill Gates today. He devoted nearly his entire fortune and the last third of his life to philanthropy. When Mr. Carnegie spoke, important people listened.

Carnegie was a progressive. He believed that society was constantly improving. As civilization evolved it created new institutions to improve the way we live. He saw that social institutions like schools, hospitals, and libraries could change the way we live for the better. New ideas and new capacities led to the building of new structures that revolutionized our society. Why shouldn't we see similar innovation and capacity-building when it comes to the question of war?

In the late 19th early 20th century, Carnegie found an answer to the problem of war in what became known as the "mediation and arbitration" movement originating in Geneva. The idea was simple. When we have disputes in domestic society, we bring them to court. Why don't we create a similar system of law and conflict management for international disputes?

Although a man of ideas, Carnegie was better known as a man of action. And "mediation and arbitration" was an actionable idea. Carnegie decided to direct his philanthropy to the building of a World Court at The Hague, and he began to lobby for the creation of a League of Nations. Carnegie believed that this idea—mediation and arbitration embedded in institutions of international law and organization—was not only rational and feasible, it was inevitable. In the modern world, war did not make rational sense. War was outmoded and it would disappear.

Sadly, Carnegie was at his full-throated best on this issue in the significant year of 1914. He was so certain of his belief in the coming abolition of war that when he founded the Carnegie Council to create educational programs that would enlighten the public on this issue, he said at its opening meeting: When peace is established, "probably sooner than expected," the trustees were to divert the remaining funds from the endowment "to relieve the deserving poor." Peace would come and the Council's work would be finished for all time.

Carnegie genuinely believed that he and his influential friends could avert World War I and set world politics upon a new course that would make it essentially a peaceful arena of public life. The history of the 20th century and the slaughter of tens of millions in world wars and genocide was a long and bitter refutation of Carnegie's idealism.

I think the best place to start our discussion is to pinpoint where Carnegie went wrong. Why hasn't war become outmoded? And why hasn't society matured to the place where we can create international institutions to handle the problem of war? Why has the great optimism of the early 20th century faded to near black?

Great talent has been devoted to answer these questions. In fact, one could argue that the entire academic discipline of International Relations was founded as a project to address them directly. But I would like to focus my contribution here to the specifically ethical dimension of the failure. And here is where the Gifford Lectures and more Scottish flavor come into the picture.

The Gifford Lectures which, as I mentioned, have attracted the world's greatest philosophers to Scotland since 1888, have a wonderful purpose. Their stated goal is "to promote and diffuse the study of natural theology in the widest sense of the term—in other words, the knowledge of God." (Since I have already channeled Andrew Carnegie and interpreted him for you, now I'll try God.)

Getting back to our question about the failure of Carnegie's inspired efforts, I want to suggest three reasons for the failure—all of which can be found in the Lectures and are echoed by today's political leaders.

I begin with Michael Ignatieff's 2003 Gifford Lecture now published as a book titled The Lesser Evil. (Ignatieff, as you may know, is now the leader of the Liberal Party in Canada.) Ignatieff implies that the first problem with Mr. Carnegie's scheme and those like it is a problem of expectation. Too many peace activists approach the problem of war with a presumption of what he calls "moral perfectionism:" Ignatieff writes:

It is naïve to suppose that we do not have to make… choices. The belief that our existing rights and guarantees should never be suspended is a piece of moral perfectionism. (Lesser Evil, vii)

…A lesser evil morality is nonpefectionist in its assumptions. It accepts as inevitable that it is not always possible to save human beings from harm without killing other human beings; not always possible to preserve full democratic disclosure and transparency in counterterrorist operations; not always desirable for democratic leaders to avoid deception … and so on… (p. 21)

Reading Ignatieff helps me to see that Carnegie's scheme may have been based on an overly optimistic assessment of human nature and politics.

Ignatieff's theme of undue idealism and accepting "the lesser evil" was echoed in President Obama's Nobel Prize acceptance speech when the president said:

…We must begin by acknowledging a hard truth: We will not eradicate violent conflict in our lifetimes. There will be times when nations—acting individually or in concert—will find the use of force not only necessary but morally justified…

…I face the world as it is; and cannot stand idle in the face of threats to the American people. For make no mistake, evil does exist in the world. A non-violent movement could not have halted Hitler's armies. Negotiations cannot convince al-Qaeda's leaders to lay down their arms. To say that force may be sometimes necessary is not a call to cynicism—it is a recognition of history; the imperfections of man and the limits of reason.

President Obama's remarks are an eloquent restatement of an essential theme in responsible democratic governance. Political life is by definition tragic—tradeoffs must be made. Perhaps the greatest and most catastrophic mistake that can be made is believing that we don't have to make tradeoffs—that power politics can somehow be bypassed or transcended. This is the dangerous illusion and delusion of many well-meaning idealists.

The second problem with Carnegie's scheme is that it had no good answer to the essential governance problem of accountability. Another famous Gifford lecturer, the American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, delivered his lectures just prior to World War II, and he was especially perceptive on this point. In his well-known book, Moral Man and Immoral Society, Niebuhr focused on the theme of collective interests.

Niebuhr pointed out that individual interests did not always coincide with group interests—group dynamics create collective action problems. This explains why it is hard to get agreement on what to do about even the most obvious challenges. While there may be common interests on a problem such as stopping genocide or addressing climate change, each actor, each nation, has a different stake in the outcome.

With this obstacle in mind, I want to suggest that what might bind us in a common approach to peace is not so much a common institution—but rather a common set of moral values and standards. These standards can be integrated into our own national projects and our existing mechanisms for accountability. To quote President Obama again:

When force is necessary, we have a moral and strategic interest in binding ourselves to certain rules of conduct…We lose ourselves when we compromise the very ideals we fight to defend. And we honor—we honor those ideals by upholding them not when it's easy but when it is hard.

The interpretation and enforcement of standards is of course a highly political issue. But the point I wish to make here is that standards do exist—and self-enforcement is indeed possible. This is why internal debates have been so hot over standards such as those embodied in the Geneva Conventions.

I think Niebuhr would tell us that the strongest instrument we have in "fighting for peace"—if I can put it that way—is moral argument itself. We can delegitimize certain kinds of actions. Just as practices like wars of conquest, slavery, and genocide have been delegitimized, so too can we continue to argue for the impropriety and unacceptable nature of terrorism and certain measures employed in counter-terrorism. In the long run, victories are secured not by force of arms—not by the application of brute force—but rather by the force and self-enforcement of better ideas. The evolution of human institutions will follow.

The third shortcoming in Carnegie's plan is the failure to deal with maximalist, and dare I say some religious, approaches to war. A third Gifford lecturer bears mentioning in this regard, the American philosopher William James. James delivered his lectures in 1900-1902 on the theme "The Varieties of Religious Experience." James was a pragmatist and a pluralist. He believed that that there was indeed something called "truth"—but that our understanding of it was in a constant state of flux and evolution. His philosophy rested on the premise that we can hold firm to the convictions formed out of our experiences, yet we must also remember the limits of our perception.

This theme was also echoed by President Obama when addressed the problem of religion and war:

…no Holy War can ever be a just war. For if you truly believe that you are carrying out divine will, then there is no need for restraint—no need to spare the pregnant mother, or the medic, or the Red Cross worker, or even a person of one's own faith. Such a warped view of religion is not just incompatible with the concept of peace, but I believe it is incompatible with the concept of faith—for the one rule that lies at the heart of every major religion is that we do unto others as we would have them do unto us…

What the president is saying is, let's be humble, let's not take politics to a realm that is beyond reason and the human experience. Let's understand that there are limits to what we can know—and certainly limits to what we should do when it comes to the use of force.

In conclusion, here are some take-away points for discussion.

First: the use of force is sadly necessary because, as has been said, evil exists in this world. We need to defend and protect—this is a duty and responsibility. However, a just war recognizes that even when force is used for just purposes such as self-defense or stopping aggression, all wars yield inevitable injustices. World War II may have been a just war, but let's not forget that it ended with the nightmare of Hiroshima.

Second: We cannot invent or design our way out of the problem of war. Internationalizing or supra-nationalizing the problem of war is not necessarily the magic answer. The performance history of international organizations is not optimal. The reason for these historic failures is simply the lack of agency and accountability that comes with the building of large and cumbersome organizations. We can't judge the justness or unjustness of a war solely by the actions or inactions of international institutions which are, by definition, structurally insufficient.

Finally, I think we can see hope on the horizon in the possibility of harmonizing standards and using the power of reason (and perhaps shame) to make the world a less militaristic and more peaceful place. It is reasonable to think the days of large-scale industrial war may be numbered. Perhaps the concept of war itself might evolve into something that looks more like cooperative policing.

Let's remember that the mitigation of evil practices ultimately comes from the assertion of core values. The end of slavery began with various revolutions and rebellions—yet the source of its eventual demise was its loss of moral legitimacy. Communism, for the most part, ended in similar fashion. The Soviet Union collapsed when the values that held it together were no longer credible and sustainable. Its legitimacy evaporated. The same can be said of apartheid South Africa. We have seen more regime change in recent years because of the power of principles rather than the power of the gun.

So yes, peace is worth fighting for. And sometimes we do have to fight. But the struggle is multi-dimensional. In today's world the character of the "fight" may be as much cerebral as it is kinetic.

And here I think we need to be self-critical. We have too quickly and too often reached for the gun. The militarism of our society seems so ingrained that we just don't see it any more. In a recent newspaper column, the journalist Nicholas Kristof wrote: "The war in Afghanistan will consume more money this year alone than we spent on the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Civil war, and the Spanish-American War—combined." The numbers are staggering (trillions of dollars for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan) and the hardware is mindboggling (everything from carrier battle groups, to drones to weapons in outer space). This doesn't even mention the human costs in casualties and in lives shattered by the experience of war. I hope our priorities will change.

Peace is worth fighting for—but that doesn’t mean a blank check for military options. There are better, smarter, more moral ways to fight. So while Mr. Carnegie couldn't solve the problem neatly, he may have been onto something quite profound—a new way of thinking that does not accept the inertia of the status quo; a new way of thinking that keeps open the possibilities of the gradual evolution of human institutions that bend toward justice.