This is the first in a series of four articles that were first posted in 2007 in the Council's online magazine Policy Innovations.

TRADE VERSUS THEFT

Because of a major flaw in the system of international trade, consumers in rich countries unknowingly buy stolen goods every day—gasoline and laptops, drugs and jewelry, cars and magazines. The raw materials used to make these goods are taken from the poorest people in the world—by stealth and by force.

The plainest criticism of global commerce today is that it flouts the first premise of capitalism. Firms currently transport huge quantities of stolen goods to consumers, violating property rights on an enormous scale. The first priority in reforming global commerce must be to replace theft with trade.

Ending the global traffic in stolen resources will require no novel theories or new international agencies. The principles of ownership and sale are well understood, and global commerce has already created institutions with the power to enforce rights of property and contract. What is required is to use these institutions to bring all resource sales into the system of enforced market rules.

THE RESOURCE CURSE

To understand why stolen goods currently flood the market, we can trace these goods back to their countries of origin. Economists have noticed that many countries with a wealth of natural resources are also full of very poor people. Resource wealth has often been an obstacle to prosperity and not its foundation. This phenomenon is known as the resource curse.

Countries that derive a large portion of their national income from high-value extractive resources—such as oil, diamonds, and gold—are especially susceptible to three overlapping curses. First, they are more prone to authoritarian governments. Second, they are at a higher risk for civil war and coup attempts. Third, they exhibit lower rates of growth.

Oil, gas, and minerals fetch high bounties, and the strongman or junta that seizes this revenue stream can buy the weapons, spies, and influence that strengthen authoritarian regimes. The money also frees authoritarians from having to collect tax revenue, making the regime even less accountable to the citizenry.

Resources also provide an incentive for civil conflict. Many rebel groups have sustained expensive armies by capturing territory and selling off the resources. Other military leaders have sold the rights to future exploitation of territory they hope to control. And coup attempts become more likely in countries with one major resource revenue source (like offshore oil) that will enrich whoever controls the national government.

Authoritarian repression and civil conflict reinforce the third aspect of the resource curse: lower rates of growth. It is estimated that the total economic cost of a typical civil war in a less developed country is 250 percent of that country's GDP at the start of the conflict. Even without such strife, the volatility of commodity prices leaves resource-dependent countries more vulnerable to economic shocks and official corruption, and instability discourages investment and development.

The resource curse casts a pall over whole societies. Resource dependence is correlated with lower life expectancy and higher rates of poverty, illiteracy, and child malnutrition. Resource abundance also exacerbates income inequality between the populace and the political elite. Because the resources can be extracted either by small groups of foreign experts (oil) or unskilled domestic laborers (alluvial diamonds), regimes that control the revenues have little incentive to invest in the education, training, or health of the people.

Approximately 3.5 billion people live in countries where extractive commodities play an important role in the economy. Of course, abundant resources are neither necessary nor sufficient for authoritarian repression, civil conflict, or low growth. For example, Eritrea has a repressive government but few easily saleable resources; and Norway has both large oil reserves and decent, representative politics.

Social scientists are still debating how to predict exactly where and how hard the curse will strike. What is so dramatic about the resource curse is how—when it hits—the wealth of a country bypasses its citizens and in fact contributes to their suffering.

ON THE GROUND IN AFRICA

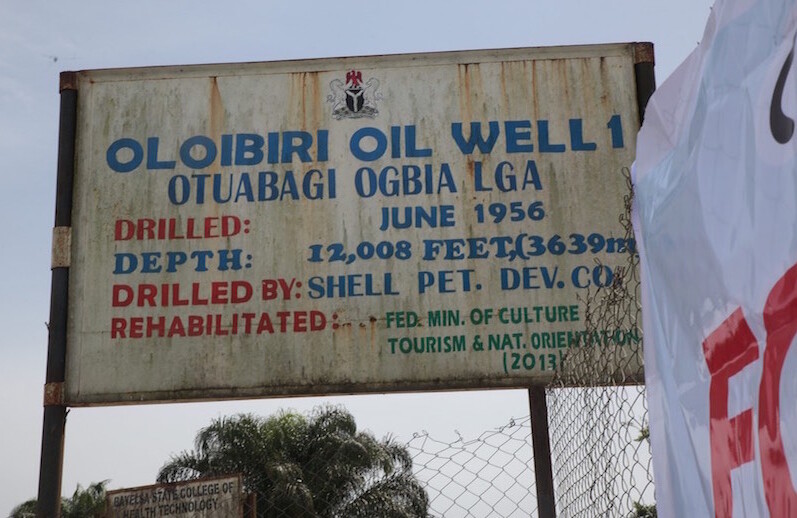

Nigeria, Africa's largest oil exporter, has a population of 140 million (larger than Britain and France combined). Between 1965 and 2000, Nigeria received a very substantial percentage of its GDP from oil revenues that totaled about $350 billion. However, in the 30 years after 1970, the percentage of Nigerians living in extreme poverty ($1/day) increased from 36 percent to almost 70 percent—from 19 million to 90 million people. The oil revenue contributed nothing to the average standard of living, and indeed the period of oil exploitation saw a decline in living standards. Moreover, inequality in Nigeria simultaneously skyrocketed. In 1970, the total income of those in the top 2 percent of the distribution was equal the total income of those in the bottom 17 percent. By 2000, the top 2 percent made as much as the bottom 55 percent. Meanwhile, corruption was everywhere evident in the Nigerian government, and most strikingly at the top. For instance, in just four years in power, General Sani Abacha and his family embezzled around $3 billion.

In the 1980s, the corrupt government of Sierra Leone embarked on disastrous economic policies and lost control over the armed gangs that were overseeing the exploitation of the country's rich diamond fields. In 1991, a small group of insurgents launched a brutal campaign of terror to gain control of these regions, including random shootings, rape, and chopping off people's hands. They recruited child soldiers and enslaved locals to work the diamond pits. With the money they received from selling these diamonds abroad, the insurgents nearly bought enough weapons to topple the government. The government was only able to defeat the rebels by trading diamond mining futures for the services of a South African mercenary force. The decade-long civil war in Sierra Leone cost about 50,000 lives, and displaced one third of the population. Sierra Leone now ranks 176 out of 177 countries on the UN Human Development Index.

Equatorial Guinea deserves special attention, as it is such a pure case of a country currently stricken by the resource curse. Equatorial Guinea is in central Africa, bordered by Gabon and Cameroon. Since 1979, it has been ruled by President Theodoro Obiang. Obiang is the kind of ruler that doesn't shy away from jailing, torturing, and killing the political opposition. He has even had himself officially proclaimed as a god who is "in permanent contact with the Almighty." In the 1990s, quite large deposits of oil were discovered in the Bay of Guinea. This discovery brought the country from obscurity to the attention of international markets at a time when Western countries were searching for sources of oil outside the Middle East. Equatorial Guinea has become the third-largest oil exporter in Africa.

Because of this huge influx of oil money, Equatorial Guinea now has the third-highest per-capita income in the world—20 percent higher than the per-capita income of the United States—yet the people have yet to partake in this prosperity. As the U.S. Department of Energy reports:

Since 1995, oil exports (currently 97 percent of total export earnings) have caused the Equatoguinean economy to grow rapidly... Despite the rapid growth in real GDP, allegations abound over how the Equatoguinean government has misappropriated its oil revenues. While the government has made some infrastructure improvements to bolster the oil industry, the average Equatoguinean has yet to experience a higher standard of living from the oil revenues.

Forbes recently listed President Obiang as one of the richest leaders in the world, with an estimated personal wealth of $600 million. The prospect of capturing this kind of wealth from offshore oil sales has attracted coup attempts, which have so far failed. And there is little doubt that the oil money has fueled significant corruption. Transparency International's latest Corruptions Perceptions Index ranks the country 152 out of the 159 countries surveyed.

Instead of using his country's remarkable oil windfall to benefit the people, Obiang has captured the new wealth and used it to consolidate his personal power. A Freedom House report paints a fuller picture of what political life is like in Equatorial Guinea at present: no credible elections, restricted press freedom, restricted rights of association and assembly, no independent judiciary, life-threatening prisons, and violence against and repression of women.

President Obiang's reign will end soon, as he is dying of prostate cancer. His tempestuous playboy son and likely heir, Teodorín, is by all accounts at least as determined as his father to control the country's oil revenues for his personal use. Given their situation, the people of Equatorial Guinea may well feel cursed by their country's new-found resource wealth.