I am sitting with Rose Niu in a Sichuan restaurant in Beijing, discussing China's environmental challenges over a spicy meal. Originally from Yunnan province, Niu is chief conservation officer of the Paulson Institute at the University of Chicago, an ambitious new "think and do" tank founded by Hank Paulson, the 74th secretary of the United States Treasury, and former chief executive of Goldman Sachs. The Paulson Institute "promotes economic growth and environmental preservation in the United States and China." Above all, it aims to strengthen the U.S.-China relationship by helping the countries to work together on priority issues.

Although the Institute is relatively new, Niu has been working on environmental issues in China for 17 years. She offers a frank assessment: "China's environment is in a crisis." Across its forests, she says, many animals and plants have disappeared—plants that may have had value in medicine or agriculture. Among its lakes, rivers and streams, many species of fish have disappeared from overfishing and severe pollution. Even considering costly efforts to restore heavily polluted lakes—Taihu in Jiangsu, Chaohu in Anhui, and Dianchi in Yunnan—there is "not a lot of evidence" that restoration efforts have had "a good return on investment."

Niu identifies three principal causes for the crisis: first, intense population and resource pressures (with 20 percent of the world's population but only about 7 percent of its arable land and fresh water); second, the process of rapid urbanization and industrialization; and third, the government's development model, with its focus on "economic development at all costs." Taken together, these drivers have generated four acute environmental challenges: "CO2 emissions; pollution, with its social implications; resource depletion; and biodiversity loss."

Lake Dianchi with the skyline of Kunming, China in the background.

A Small Fish Can Swim Far

Niu has a compelling view of the big picture. But her environmental work in China began very much at the grassroots level. In 1997, while living in New Zealand, she got a phone call from the Nature Conservancy (TNC). A member of the minority Naxi population from Yunnan, Niu had been outside China for several years. TNC explained they were hoping to establish a conservation project in northwest Yunnan—centered on the city of Lijiang, her hometown. They had identified the area as a "global hotspot" for conservation, and needed her help to get started. Niu accepted the invitation, and became TNC's first employee in China. Work began modestly enough, with $2,000 USD in cash, and a mandate to establish the program. She returned to Lijiang, and "started from scratch," using her parents' home as an office and living space.

Supported by TNC's headquarters in the United States, Niu was also joined in Yunnan for six years by Edward M. Norton, who served as a senior advisor in helping establish TNC's China program (Edward M. Norton is the father of the Hollywood actor Edward H. Norton). One of their first was projects supporting the Yunnan government in applying to UNESCO to designate the Three Parallel Rivers region as a world natural heritage site. In 2001, UNESCO provided the official designation, describing the area as "an epicentre of Chinese biodiversity."

Tiger Leaping Gorge, part of the Three Parallel Rivers World Natural Heritage Site

Starting in 1999, as chairman of the global board for TNC, Hank Paulson began visiting Yunnan to support TNC's efforts there. In 2001, he went with Niu and Norton to Beijing for a meeting with Jiang Zemin, then president of China. The meeting went well: President Jiang was open and good humored as they explained their conservation activities in Yunnan. With President Jiang's blessing, Niu opened a Beijing office for TNC in 2002. From there it snowballed: between 2002 and 2008 Niu grew TNC in China to five offices and 86 employees. When I ask Niu to reflect on her most important achievements over these years, she says "it's hard to answer this question, because I am a small fish in a huge pond." With a bit of prompting, however, three areas emerge where she and her colleagues have made a significant contribution.

First, TNC was "a pioneer" among green NGOs. When she started in 1997, Niu recalls, "not many local officials understood the value of conservation and philanthropy giving; these were new concepts." It also helped that Niu was a local: many people suspected that TNC had a "hidden agenda" in sending money from so far away for non-for-profit work. If they had only sent a foreigner, the venture might well have failed. Instead, Niu was able to build trust and serve as a bridge across the two cultures. When TNC's work in Yunnan became a flagship for conservation in China, the project "helped demonstrate what philanthropy can do for the environment."

Second, TNC introduced the concept of a "national park" to China. They helped the Yunnan government establish several pilots for national parks, and organized study tours for Chinese government officials to visit national parks in other countries. The seed took a long time to bear fruit, but in November 2013 the Chinese central government announced that as one of the 363 specific reform tasks, it would establish a national park system in China. "In conservation work," smiles Niu, "one has to be patient." Finally, TNC has helped improve biodiversity conservation in China. It worked with the Ministry of Environment to develop a national blueprint for biodiversity conservation, and identified 35 conservation priorities across the country which have informed China's first biodiversity conservation action plan.

Point of No Return, or Shining Light Ahead?

Since those early days, a lot of Chinese conservation NGOs have also emerged, and they are making important contributions as well. But despite these admirable efforts, Niu reiterates that conservation "is a long term struggle," and the struggle has only intensified alongside China's economic growth. Here she confesses to a deeper worry: "China's environment may have reached a tipping point—a point of no return. Once ecosystems have been degraded to a certain level, we may not be able to bring them back."

Yet there is also, she says, some basis for cautious optimism: one "shining light" is the new administration's talk of "eco-civilization," and some of its reforms in support of this objective. But make no mistake, says Niu: tinkering will not solve the problem. Rather, China's development path needs to shift "to a new paradigm, with ambitious new plans and policies."

For starters, there must be incentives for local government decision makers to prioritize environment and conservation. There must also be much better enforcement of environment laws, as well as intensive capacity-building at the grassroots level to support local officials. In addition, much more money must be allocated to environmental protection, especially conservation of ecosystems and biodiversity. Lastly, there must be much more public awareness. There were tens of thousands of protests in China in recent years related to environmental concerns, but most of the protests were related to pollution and land use decisions. In contrast, says Niu, "not a lot of Chinese know or care about biodiversity loss or ecosystem degradation." If the public raised more concerns in these areas, "it would provide an incentive for politicians to prioritize them."

A Champion for China's Environment from Abroad

In 2010, after 13 years with TNC—including two years as deputy managing director for TNC in North Asia between 2008 and 2010—Niu was invited to lead the China Program for World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in the United States. From Washington, D.C., Niu raised funds and provided technical support for WWF-China. It was a rich learning experience: while TNC tends to "go deep" on a few issues, WWF "touches on almost every single issue" related to the environment and conservation.

All was going well. Then in late 2012, Paulson approached Niu to ask whether she would be interested in leading conservation programs for the newly-formed Paulson Institute. By this point, Niu had known him for 15 years. While most people know him as a prominent investment banker, Niu emphasizes that "he has also been a donor and supporter of conservation work for much of his lifetime." She was excited to think about what could be achieved at an institute under his leadership, with his potential for influence at the highest levels. So she agreed to join his institute as its chief conservation officer.

Niu acknowledges there are tradeoffs in working on environmental issues in China from outside the country. Those working inside China can engage in advocacy more directly, and stay more up to date on what is happening. But her work circumstances also present some unique opportunities. In working closely with someone as influential as Paulson, there is "more potential to influence larger policies" in the global context.

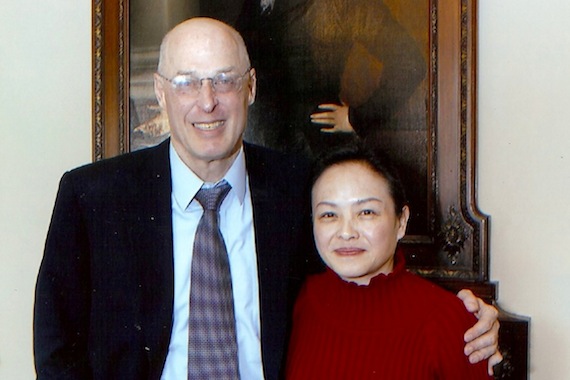

Hank Paulson and Rose Niu

In a recent column for the The New York Times, "The Coming Climate Crash," Paulson describes in plain terms the ambition of his Institute to play an intermediary role between the United States and China on climate change and other environmental issues: "When it comes to developing new technologies, no country can innovate like America. And no country can test new technologies and roll them out at scale quicker than China...The Paulson Institute...is focused on bridging this gap."

In her first 18 months at the Institute, Niu has joined Paulson in meetings with Xi Jinping, the president of China, Li Keqiang, the premier of China, and Wang Yang, the vice premier responsible for forestry issues. She is encouraged that China's senior leadership has been receptive and supportive to the Institute's outreach and efforts.

While Niu feels it is still early days to highlight her achievements at the Institute, several important initiatives are underway. For example, inside China, they have been invited to work with the National Development and Reform Commission—which is leading the establishment of national parks throughout China—to share lessons learned from the U.S. park system. They are also working with the Chinese Academy of Science and State Forestry Administration to develop a national blueprint for coastal wetland conservation. And they have taken on a critical challenge in attempting to conserve several critical wetlands along China's coastline.

"There is a big conservation gap here," says Niu: the 11 provinces on the coast have 40 percent of China's population and 60 percent of its GDP, so "development and human population pressures" are especially high in this region. Since land is more expensive, conservation is "a harder battle to fight" here than in places like Yunnan or Qinghai in the west. Still, Niu feels that they are "making good progress."

In the international arena, too, the Institute is helping to connect the dots between China's economy and global environmental stewardship. They are working with the China Development Bank to enhance environmental risk management in its lending practices, both at home and abroad, and they are working on "greening supply chains" of multinational and Chinese companies to help ensure that soybeans imported to China from Brazil and Argentina are in compliance with local laws and are not contributing to deforestation. It is a tall agenda, but the Institute seems well placed to pursue it.

Hangzhou xixi wetland landscape

Keep on Keeping On

Niu is uncertain whether or not it is too late to turn around China's environment. But she hopes that the eco-civilization paradigm now emerging inside China, and innovative forms of collaboration between China and the United States, may together begin to undo the crisis. She points out that Chinese traditional culture should be rediscovered: "Traditional Chinese culture has a lot of good philosophies about the relationship of human beings and nature." In Niu's minority Naxi culture, for instance, "people traditionally protected the river and lakes of our land carefully. Unfortunately, these traditional local roles are lost now." Perhaps the path to China's future, she suggests, is to rehabilitate some of its older traditions and values.

I ask her if she has a final message for others seeking to effect change. She considers for a moment: "Leadership is not about authority. It is about having influence by sharing expertise. And if you want to influence others, you need to sit at the same table." Niu has sat together with villagers in Yunnan, heads of state in Beijing, and everyone in between, always with the same message, looking to conserve what is left to be saved, while there is still time.