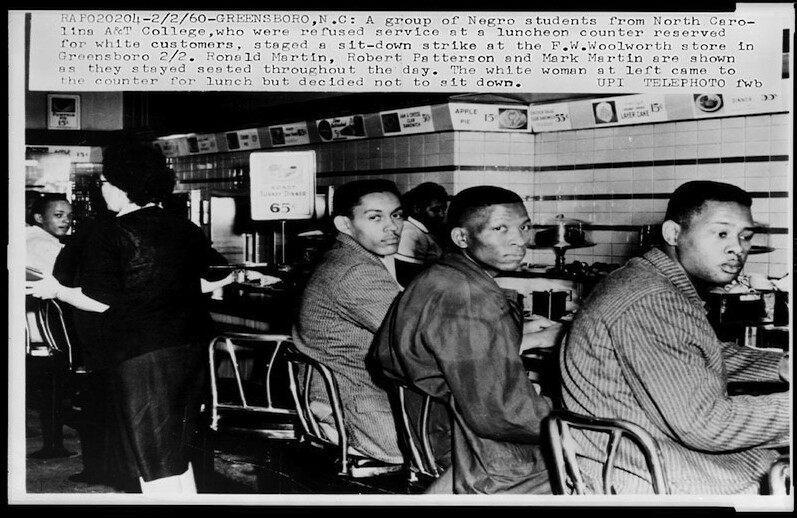

In 1960, the United States was engaged in an ideological campaign against the Soviet Union, declaring that freedom and democracy would prevail in the global order. At home, as evidenced by lunch counter sit-ins, it was clear that these "American principles" were not being applied to minority groups.

The editors of WORLDVIEW Magazine called for a change in the way that minorities in the United States were treated, arguing that "...one of the most important challenges we face in the Cold War is to set our own house in order, because a nation that is unwilling or unable to secure justice within its own borders cannot hope to be the symbol and defender of justice for the rest of the world." They stated that churches needed to play a larger role in the civil rights movement, as they remained one of the most segregated places in America.

WORLDVIEW Magazine ran from 1958-85 and featured articles by political philosophers, scholars, churchmen, statesmen, and writers from across the political spectrum. Find the entire archive online here.

Americans traditionally have liked to make a sharp distinction between domestic and foreign affairs, between "our" business and "their" business. The events of the past two decades have taught us, however, that the distinction is generally unreal. No man is an island and today no nation is an island; we are all involved in each other's fate and what happens “here” inevitably affects what happens “there.” A whole world watches to see how this nation manages its “private” problems and, inevitably the pattern of America's domestic life has effects on life abroad. During the past several years Mr. George Kennan has repeatedly reminded us, for example, that one of the most important challenges we face in the Cold War is to set our own house in order, because a nation that is unwilling or unable to secure justice within its own borders cannot hope to be the symbol and defender of justice for the rest of the world.

In this respect, no problem in American society is more basic or more urgent than the problem of America's minority groups. This nation will be judged on how it treats them. Are we in fact a pluralist society which promotes genuine equality of opportunity for each of its members, or is American “equality” only a myth? Our society is struggling to answer this question. And on the answer a great deal of our future in the world depends. The form this question has taken is both racial and religious; it involves two of our most numerous minorities: Negroes and Catholics. In dealing with the questions they are now asking America's conscience is being put to a great test. Are we—in spite of our fine democratic professions—determined to maintain ourselves as a white-Anglo-Saxon-Protestant culture, or is this indeed a land of “liberty and justice for all”?

America's racial problem is its greatest trauma. The American Negro has suddenly awakened from a long, docile slumber to demand an active role in the nation's life. The lunch counter demonstrations now taking place in the South are not the work of a few hot-headed youths: they are a historic sign: that the American Negro is finally, a hundred years after emancipation, demanding first-class citizenship. The Negroes' struggle has thus moved beyond the courts, beyond legalism; it has become immediate and personal and calls for an immediate and personal response from the nation's white majority. The time when this majority could be neutral about; or detached from, this question—content with the “status quo”—is forever passed. On the Negro question there is no status quo: all is in ferment.

If a better measure of justice, a better America, is to emerge from the ferment, the nation's religious groups will have to play a more active role than they have in the past. It is still a bitter fact that in the United States 11 A.M. on Sunday is the most segregated hour in the week. America's Churches, on the whole, have a sorry history here; in their approach to Negro rights they have lagged behind the best insights of the secular-humanist conscience; they have rationalized and temporized and, sometimes, connived with injustice. For all this they have much to answer. Perhaps their major role in the social order now is to guide and speed the real emancipation of the American Negro that has finally begun.

The Churches—especially the Protestant Churches—face a similar challenge and have a similar role in that other “minority” question that is now dividing the nation: the question of a possible Roman Catholic candidate for the Presidency of the United States. And here the question is one of particular psychological delicacy for some Protestant Americans, since it may seem to threaten their traditional image of America as an unofficially “Protestant” nation. But the challenge for the Protestant conscience here is similar to the challenge for the white conscience in regard to the Negro: it is whether the American promise shall finally be made real for groups other than one's own. The most damaging disservice that can be done to American society—and to America's image in the world—is a continued denial to any “other” group of participation in the full opportunity of American life. The test for America’s maturity and claim to world leadership will be its success in dealing with its own minority problems.