Princeton's Gyan Prakash tells the tragic story of the Amritsar Massacre in 1919, in which a British general ordered his soldiers to shoot at thousands of unarmed civilians, and its galvanizing effect on the Indian independence movement. Was this violence an "exceptional" moment in Britain's colonial history? And how did it change Gandhi's thinking in relation to his strategies to resist colonialism?

TED WIDMER: This is Ted Widmer, and you're listening to The Crack-Up, an occasional podcast series about the year 1919.

Today we're really happy to welcome Gyan Prakash. He's a professor of history at Princeton University. Welcome, Gyan.

GYAN PRAKASH: Thank you. Glad to be here.

TED WIDMER: Thank you for your wonderful piece about the Amritsar Massacre of April 1919. Can you tell us a little bit about the basic events around the massacre?

GYAN PRAKASH: What happened was that on April 13, Brigadier General Dyer led a group of soldiers. Most of them were actually Indian, but he was a British soldier heading Indian troops under his command. They drove into this public garden called Jallianwala Bagh. The entry was very narrow, so they got off the armored truck and went to this public square, public garden, where many hundreds of unarmed civilians and women and children had gathered. It was a day of a festival, so there was a kind of festive air to the place.

Without warning, General Dyer ordered his troops to fire on the crowd. They fired for about 10 minutes, and about 379 people by official count died, and many thousands were injured. The unofficial count was much higher, but anyway we know only the official count.

TED WIDMER: It goes against the grain of the simplistic way a lot of us have learned about the year 1919, which is that a great war had ended and people were returning to their peaceful occupations. It's really a very different kind of story, isn't it?

GYAN PRAKASH: It is. It is also a different story in relation to British rule because it was seen as an exceptional moment, that British rule had never been associated with violence. In fact there has been a great deal of work more recently by historians exploding that myth, that British rule had always been accompanied by what they call "small wars," small counterinsurgency wars, which were always accompanied by violence.

What was maybe exceptional about 1919 was that first, it was unexpected. Indians had expected that after the end of the war, the British, having won the war, would be generous toward Indian demands, and they were not. Having introduced a bill that was popularly known as the Rowlatt Act after the war, which continued all the wartime restrictions on speech and assembly, Indians were really taken by surprise.

That was the kind of exceptional aspect of that moment. You would have expected the British to be generous and more accepting of Indian demands, but they were not.

TED WIDMER: Indians had contributed in many ways to the war effort, is that not right?

GYAN PRAKASH: They had. You know, Gandhi famously had actually supported the British in the war. There was an expectation that that loyalty would be rewarded by some concession to their demands, but that was not to be.

TED WIDMER: Also, there's a great deal of rhetoric in the air coming from U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, that the old ways are basically over, that three large empires have fallen as a result of the war, and democracy now will spread, or so Wilson led millions of people to believe. But it wasn't really that simple, was it?

GYAN PRAKASH: Yes. And there was globally an expectation. We have the May Fourth Movement in China happening almost at the same time, and so across the world there was an expectation of a let-up in imperial command and that there would be greater concessions to demands that were being raised.

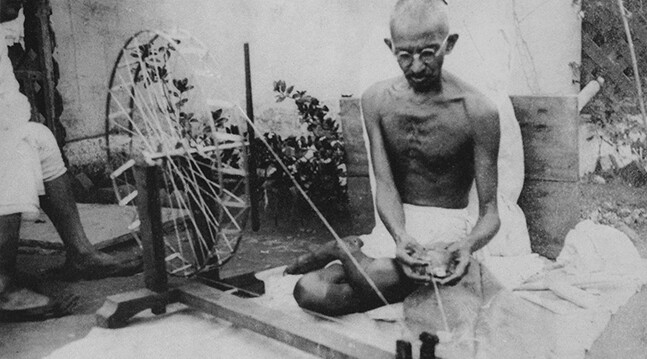

Gandhi appears precisely at that moment. He had come back from South Africa in 1915, and he had led various kinds of local movements. The Rowlatt Act really provided him the first opportunity to launch a country-wide satyagraha against the British rule.

TED WIDMER: Where was he when the massacre happened?

GYAN PRAKASH: He had actually a few days before tried to travel to Amritsar because even before the massacre happened things had been heating up in Amritsar because there was a live nationalist movement, and he thought he would go there and address meetings and so on.

In fact, Gandhi had called for a nationwide general strike on April 6, seven days before the massacre, and he had asked people to engage in nonviolent activities during that day, observe a day-long fast, and hold meetings, and demand that the legislation be withdrawn. Following that, he traveled to Delhi on his way to Amritsar, but just before Delhi he was taken off the train and sent back to Bombay. So he was back in Bombay when the massacre actually happened.

TED WIDMER: Was there any sense of a warning that something was coming? Tensions, as you said, had been high for a few days beforehand, but no one was expecting to see civilians killed in such high numbers.

GYAN PRAKASH: There hadn't been an expectation of this kind of violence, but the tensions had been very high for several days leading up to April 13. It so happened also that General Dyer in particular took upon himself to what he called "teach Indians some moral lesson."

The British at this time, given that Gandhi had called for a nationwide strike, they had the memory of the 1857 Rebellion very much in their minds. That was playing on their minds that if we allow this to continue, it might soon escalate into a violent rebellion across the country. So, the fear of sedition was very much on their minds, and that was one of the reasons for the kind of response that General Dyer took.

TED WIDMER: It's fascinating in your piece when you bring up the Great Rebellion of 1857 and also that the British Crown had not been in direct control until 1859. So there is a lot of older history in the air at Amritsar.

GYAN PRAKASH: That's right. Throughout the British rule, from about the late 18th century until 1857 there had been a number of local rebellions, and those rebellions had often been put down with violent force.

The British rule, it's interesting that they represented themselves as bringing in the rule of law, but the fact was that they were ruling an alien population. So they always had, right from the early 19th century, a set of extraordinary laws in force where they could arrest people and restrict any judicial scrutiny of executive actions. That was always part of British rule. The Rowlatt Act really was a kind of continuation of that.

If you keep in the background this long period of counterinsurgency—there's a British historian called Kim Wagner, who has done a lot of work on both the Amritsar massacre as well as many of these counterinsurgency efforts by the British. He argues very powerfully and shows that violence and extraordinary laws had been always part of British rule. It's just that in the context of 1919 and with the memory of 1857 all of these come together and create this kind of extraordinary moment.

TED WIDMER: Is there a religious or ethnic component to it? You mention that Amritsar is a Sikh holy city. Were Muslim-Hindu tensions in the air at all, or was it a united Indian response against the British?

GYAN PRAKASH: Actually, in fact not. What happened in the previous four or five years, there had been mobilization which included Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs. Although the nature of leadership and the mobilization often followed religious lines, there had been a united leadership at the political level among these different religious leaders against the British.

Of course, the other complicating factor was that after 1857 the British had recruited their troops heavily from the Punjab because they thought the Sikhs were a martial race, and Sikhs had been largely quiet during the rebellion. So they were seen as a loyal force. Now, after World War I, many of these Sikh troops were demobilized, so there was also this fear that these people had been trained in arms and ammunitions. Many of them had fought in the First World War in the European and African theaters and had come back with different ideas about the Empire.

So there was also this fear that here is a kind of rebellion. The leadership is united across religious lines. Added to this combustive mix is the presence of the demobilized soldiers.

TED WIDMER: That's so similar to what's happening in the United States with a lot of anxiety provoked by the return of all these African American veterans, who are very confident and have learned a lot about citizenship and don't want to be second-class citizens anymore. It's a striking parallel.

GYAN PRAKASH: Yes. There is that factor. That factor is there in the nationalist mobilization itself, and it's also there in the British fear of what would happen.

TED WIDMER: Does the memory of Amritsar become a galvanizing factor for Indian independence a generation later?

GYAN PRAKASH: Yes. I think when the massacre happened the news spread very quickly, although there was censorship imposed. But by the end of April the news had spread across the country, and the Congress was of course mobilizing. The Congress had become for the first time a kind of mass nationalist organization.

There was revulsion across the country that the British could open fire on an unarmed civilian population. That was really a kind of catalytic event in mobilizing nationalist opposition.

You can see that, even though Gandhi calls his satyagraha a "Himalayan" blunder because he thought it led to violence, but by 1920 he had also concluded that the British rule had to be opposed with mass nonviolent resistance.

TED WIDMER: So he did not take the lesson that nonviolence was destined to fail. He remained confident in nonviolence.

GYAN PRAKASH: He remained confident. I think one change that he made was that after the Amritsar experience when he thought that the response to the Amritsar Massacre had led to spontaneous violence among the people he decided that any future nonviolent resistance must be led by a firm group of satyagrahas, people who firmly believed in his ideas of nonviolence.

When he launches the movement in 1920—and particularly, there are a lot of violent incidents in 1922 in a village in North India where villagers set fire to a police station, killing 22 people. At that point, Gandhi withdraws the nonviolent movement, and he says that people haven't really understood the lesson of nonviolence.

He becomes firmly convinced after that that any movement that he launches must be under the leadership of a dedicated band of followers who believe in nonviolence.

TED WIDMER: How do the British react? Do they get the news immediately? Is it filtered? And then, how do different segments of the British population respond?

GYAN PRAKASH: Back in Britain opinion was divided. There were some—even Churchill, in fact, for that matter—who condemned what had happened, but there was a significant section of British official opinion which was in favor of Dyer. They believed that he had been unjustly punished, and when he returned he returned as a hero in Britain. Because Britain had a significant imperial lobby, people who believed in the idea of imperialism, and there were organizations that promoted that idea. So they were in favor of what he had done. It was necessary in their view to maintain the Empire.

Within the colonial bureaucracy in India there was widespread support for Dyer. Only in the top level, where they had to take into account public opinion and condemnation from all around, there was criticism there. But at the middle level of the bureaucracy, both civilian and military bureaucracy in India, there was widespread support for him.

TED WIDMER: Did he lead a long life of retirement with no consequences especially?

GYAN PRAKASH: I don't think he ever lived down that reputation. I'm not 100 percent sure of what he does finally after he returns to Britain, but from what I remember I don't think he again gains any kind of official position.

TED WIDMER: When we reach the centennial, there were a number of observances both within India and British gestures toward India. Were they enough in your opinion?

GYAN PRAKASH: Yes. There has been a call for apology. The British have never apologized for what they did. There were those calls.

Of course, this was a centennial, so there was more commemoration of the event this year compared to previous years. But Jallianwala Bagh has always been kind of seared in Indian memory as an event that finally exposed how violent the British rule was and that it was the trigger for the mass nationalist movement.

Growing up in India even as a child I remember in school reading about the massacre. Every schoolchild in India reads about this and remembers it as the moment when the British fired on unarmed civilians.

TED WIDMER: Would you say it's analogous to May Fourth in China? You mentioned that earlier. That's a date that all Chinese people know very well. Is it the same kind of public memory in India?

GYAN PRAKASH: Exactly, yes. I think all across the political spectrum in India today the memory of Amritsar 1919 is I think one of the most important ones in the annals of the Indian nationalist struggle.

TED WIDMER: It is really a profoundly important contribution to our series and the times because we're trying to show how hard democracy is, and how hard it was in 1919, and how high the mountain was. You mention Gandhi called his mistake a "Himalayan" mistake, but how high these mountains were that people were trying to climb up as they strained toward their own "self-determination," in Wilson's phrase, and it's just a very difficult year for a lot of different reasons.

GYAN PRAKASH: Yes. Also, I think just in relation to democracy, one of the things that Gandhi does which is really remarkable, if you think of the time in 1920, he turns the Indian National Congress into a mass organization. Anyone can pay a very nominal membership fee and become a member.

If you think of 1920 that's quite a revolutionary step where contrary to liberal theory, which expected people to have education in order to have a vote, Gandhi was saying illiterate peasants of India can be possible citizens, and all you need is membership in this nationalist organization.

TED WIDMER: Fascinating.

GYAN PRAKASH: It is quite a revolutionary step, and it comes in the wake of Amritsar.

TED WIDMER: So, like all tragedies, people learned from it, and there were improvements that came in the years that followed.

GYAN PRAKASH: Yes, yes. It was a moment of sadness, a tragedy, but also it inspired people to mobilize.

TED WIDMER: That's a great note to end on, Gyan.

GYAN PRAKASH: Thank you.

TED WIDMER: I'm so grateful for your time today and for your wonderful piece.

GYAN PRAKASH: You are most welcome and thank you for asking me.