"This has happened before where we've had a great power who is essentially the leader of the international system taking a transactional approach. The closest example would be maybe Bismarck in the 1870s until the eve of World War I. There it worked quite well. . . . The drawbacks of this, of course, are that it is highly unstable."

Podcast music: Blindhead and Mick Lexington.

DEVIN STEWART: I'm Devin Stewart here at Carnegie Council in New York City. Today I'm speaking with Raymond Kuo. He is here in the studio with us. He is assistant professor of political science at Fordham University where he studies international security.

Raymond, thanks for coming today.

RAYMOND KUO: Thank you for having me.

DEVIN STEWART: You study and research and lecture about the state of the international system and international security. With the Trump administration as the new factor in the international system, how would you describe, in big-picture terms, where we are today?

RAYMOND KUO: The current international order that we have was founded by the United States after World War II, so it has lasted for 70 years, and it has been 70 years of bipartisan support for the idea of robust American military engagement and free trade in order to help developing countries get up on their feet and advance economically, and also democracy.

Unfortunately, Trump seems to be attacking every one of those pillars. He calls NATO "obsolete." He pulls out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), talks about maybe trying to renegotiate The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) or the World Trade Organization (WTO), and has an affinity for authoritarian personalities.

In all three areas it seems like the United States is pulling back from its traditional seven-decade role of international leadership, and that's causing a lot of concern around the world. Asian countries in particular are worried that they can no longer rely upon American security guarantees, and that the United States will not take an international leadership role in terms of helping them develop trade links and in development more generally.

DEVIN STEWART: So Trump's attack on these pillars of the current international system that has been around for, as you said, 70 years, do they sort of add up to something that is coherent? Do you have a sense of why he's doing this, and does he have a point at all?

RAYMOND KUO: It is a matter of significant debates whether or not there actually is a coherent "America First" strategy or if this is all just kind of winging it.

I think personally the best way to understand it is through two lenses: One is a matter of deinstitutionalization. On the domestic level we often see people criticizing Trump for trying to hollow out the State Department, hollow out the various administrative organs of government, to attack what he supposedly calls "the deep state."

We can see that at the international level as well, a turning away from international institutions, away from what we call "general reciprocity," where everyone abides by clear rules of conduct, and turning instead to a more transactional foreign policy, where it's "you scratch my back and I scratch yours." But that's the limit of our relationship; we have nothing beyond the pure transactional cost-benefit analysis.

The second part of it would be that you can also see this as sort of a retrenchment or a little bit of isolationism; that the United States wants to pull back and sort of lick its wounds from all the international engagements during the G. W. Bush era, as well as the Obama era.

I think that's a little bit too coherent. I think that gives him a little bit too much credit; because if that were so, then you would still want to have effective people in the Department of Defense (DoD) or the State Department to manage that withdrawal. Instead, Trump has just inflated the DoD budget but also cut back significantly on hiring for the State Department. So I tend to think of it as sort of a deinstitutionalization, a de-governancing of both the domestic as well as the international spheres.

DEVIN STEWART: What are the pros and cons of this approach? Are there some merits? Looking at things in a zero-sum fashion, is there anything positive you can say about this?

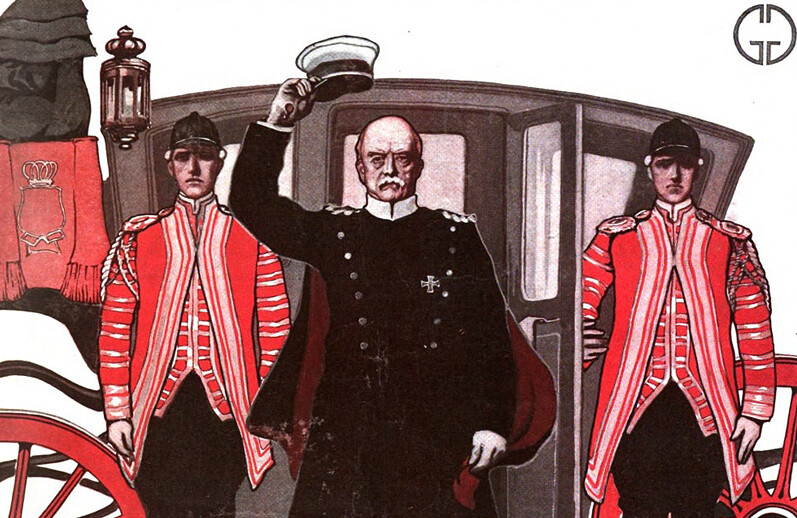

RAYMOND KUO: Oh, absolutely. This has happened before where we've had a great power who is essentially the leader of the international system taking a transactional approach.

The closest example would be maybe Bismarck in the 1870s until the eve of World War I. There it worked quite well. You had a master statesman who was straddling the world stage and balancing all these different international pressures and domestic pressures and keeping it in an uneasy balance, but that ultimately led to a German empire and led to Germany being the strongest continental power in Europe.

The drawbacks of this, of course, are that it is highly unstable. When we think about that era there were a lot of alliances that failed, a lot of defection, a lot of backstabbing and secrecy, and also, of course, a lot of conflict and war. When you mix in modern weaponry and nuclear warfare, that's just a very dangerous mix. I think, generally speaking, we want to have less instability right now, and a transactional approach by the United States actually increases that instability.

DEVIN STEWART: If we're lucky, we have Bismarck in the White House.

RAYMOND KUO: Right.

DEVIN STEWART: You mentioned the World War I parallels. Do you see any other similarities between where the world was before World War I and where we are today?

RAYMOND KUO: Yes. You have in many cases at least two antagonistic actors: the United States and China—maybe a few more; we can toss Russia into the mix as well—who all exist in a sort of uneasy balance of power. Then you have proxies, most notably North and South Korea, where a conflict between these two actors on a peripheral issue or a peripheral area can ignite a major conflict between the superpowers, which is something that nobody wants to see, but that's exactly what happened in World War I, where you had Serbian nationalists kill the Austrian archduke, and this tiny little conflict caused 20 million deaths within the war and another 20 million from the flu that happened afterward.

So there are a good number of parallels here about a rise in tensions, the inability to shift the benefits of the international system to accommodate this rise in power, instability in peripheral areas, and that can all lead to war.

The good thing is, however, that we have a significantly greater degree of trade. Why fight when you can just trade with each other? So that helps to tamp down conflict.

I would have said that we had less nationalism, but I don’t think that is true anymore actually. With the Chinese, President Xi Jinping has made a really strong push for nationalism because as the economy is slowing down he has to find another pillar of domestic legitimacy, so that is what he aims for.

With the United States, obviously, it's a sort of "America first" rhetoric. And if you look at around the world, North Korea is heavily nationalistic; Russia as well; India and Pakistan; the Philippines too with Duterte. So you are seeing this rising nationalism, and really the only thing that we’re hoping that will hold it back is democracy—which seems to be eroding in a variety of different places—and trade, which the United States is pulling back from. It leads to a highly unstable environment.

DEVIN STEWART: This rise of nationalism worldwide, what do you think the causes are?

RAYMOND KUO: If I knew, I would have a book out already.

DEVIN STEWART: I'm sure lots of people are writing those books as we speak.

RAYMOND KUO: I think the common view is that it's a backlash against globalization. But that's kind of hard to square. The most recent studies that have come out of Europe and the United States suggest that it's not the people who have been most deeply hurt by globalization that support this sort of nationalism. It seems to be a matter of culture and identity; that people are unable to shift in some way, to accept that there are a lot more immigrants coming in, that the culture or personality of a country, of your country, is changing rapidly. So it's that kind of a backlash, not so much one of economics, but ethnic, even racial, fairness to some extent? That would be my best guess.

DEVIN STEWART: I think those are very astute.

You have written about trying to assess Trump's approach in diplomacy, and this series is about Asia-Pacific in particular. You’ve mentioned the phrase "triangular diplomacy," and you've also mentioned his approach as "transactional." How would you describe the Trump approach to Asia?

RAYMOND KUO: I mentioned triangular diplomacy toward the beginning of this year when it seemed like the Steve Bannon wing of the White House was pretty much a center, or dominating. They have this kind of weird mélange of ethnic-religious nationalism, sort of a white Christian identity, and they saw the Chinese as the next major threat. So their idea was to get together with the Russians and play them off against the Chinese; kind of what Nixon did with China in reverse against the Russians.

With Bannon not being quite as strong in the White House, and I think just some of the geopolitical realities that you can't necessarily trust the Russians in terms of having a grand geostrategic alignment, that has kind of fallen by the wayside. So the transactional approach of Trump's diplomacy, of "you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours," has really come out. We see this in a number of different areas.

With the Chinese in particular, he had on the campaign trail decried the Chinese as "currency manipulators," as "a major threat," as causing global warming somehow. After a couple of meetings with Xi Jinping it was pretty clear that he had made a clear shift; that he recognized that the Chinese have to help us. If we want to get any traction with North Korea, the Chinese have to help us with that issue, as well as things like cybersecurity and trade. We need the Chinese's cooperation. So this sort of transactional approach reared its head pretty quickly. He may have had a principled stance beforehand, but it very quickly turned into, "Well, so long as the Chinese can help me on these particular policy points, I'll accept it."

DEVIN STEWART: Are you hopeful that maybe there's a learning curve and things are improving, or how do you see the normative trajectory of the Trump approach in Asia? What is your assessment?

RAYMOND KUO: Unfortunately, I don't think he's learning all that well, or if he is, it's not showing up. I think part of that has to do with the fact that major organs of diplomacy, like the State Department or the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), or even the Commerce Department or the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR), they just really haven't been staffed. So even if Trump has learned and has decided to pursue a different set of policies, it's not actually going to go from the Oval Office to the bureaucracy and actually be implemented because there's just nobody there to implement it.

In terms of whether or not he's actually learning, I tend to think not. His latest tweets about North Korea and saying, "The Chinese weren't able to coerce North Koreans," at least he knows that they tried. I mean it’s kind of diplomacy 101. That's (A) a pretty odd statement to make, and then (B) you are exonerating the Chinese when you still need their cooperation, and you haven't lined up any sort of institutional backing. It's not like you said to the Chinese, "Okay, I take it you made a good-faith effort,"— and there are some questions about that—"you made a good-faith effort and it didn’t work." So what's the next step? How do you get both American and Chinese cooperation together—you have some basis here—and push against the North Koreans?

The way that at least the tweet made it seem was: "Oh, you made your best effort. We're just going to drop this. We'll just deal with this on our own, or we'll deal with this through some amorphous plan that we don't actually have." So there’s a lack of long-range thinking, and I think that's probably the clearest sign of him not learning.

DEVIN STEWART: It sounds like you're taking his tweets at face value. That suggests one way of interpreting. Aren't there other ways to interpret it, that maybe it's a sort of second, parallel way of communicating while other things are happening on the sidelines?

RAYMOND KUO: Sure, yes. But then the question is, all right, if he's making it for a domestic audience, I suppose fair enough, although I don't know how many Americans are actually all that interested in the issue of North Korea.

But more importantly, I think, the issue is that there is no cheap talk in international affairs. Throwaway phrases made by the president of United States will always be hashed out and deeply analyzed by analysts all over the world. During the transition period when Trump had a conversation with, I think, the Pakistanis, and it made it seem like the United States would support the Pakistanis against the Indians, the Pakistanis took the liberty of publishing that entire conversation, or at least paraphrasing the conversation, because they figured, "Look, this guy is serious, he means what he says, that's his whole campaign shtick. We are going to take that and leverage this for international support against India."

Trump I think subsequently backed off from that. But the fact that he keeps tweeting things which seem to be—and the fact that Sean Spicer occasionally says that they actually are policy statements by the President—makes it really uncertain. If you were an international actor, you would probably default to assuming that it is an official statement, because otherwise what are you supposed to do? Which one am I supposed to discount or not? And in a negotiation I could always use that phrase and come back to him as a point of leverage.

DEVIN STEWART: One of the themes of this series is looking at sort of worst-case scenarios, what's possible in the Asia-Pacific region. One of your major areas of research is the cause of war, which would be very interesting to hear about.

So a two-part question really: Give us your sense of what causes war in the international setting. Everybody has a theory; I'm sure yours is probably better than most. And the second question is, given your understanding of the causes of war, what are the risks for Asia?

RAYMOND KUO: I think the general perspective is that war is kind of easy to explain; you have a Hitler who is just a crazy madman; he's going to go launch into war and everybody's got to stop him. Or there's some sort of principle or value that you fight for. But war in political science is actually very much a puzzle, because it's incredibly costly, and once we throw in nuclear weapons it's unimaginably costly. So why can't states negotiate their way out of a war? Why shouldn't they be able to stop right at the line, get what they want, and demonstrate their resolve, and then fall back because war is just all that costly?

I think there are two methods here. One is what we might call "unintentional war," or having some sort of reason not to bargain. In this case when we think about the Asia-Pacific region there are a lot of tensions. You've got Taiwan, South China Sea, North Korea. I'll set aside India and Pakistan because I'm not all that well-versed in it. We have all these tensions right now, but none of them have fully spilled over into conflict. It needs something else. Conflict alone doesn't give you war.

So what would give you that war? One is an accidental war: a collision in the South China Sea between, let's say, a U.S. destroyer and a Chinese fishing vessel; or one of those man-made islands that the Chinese have launches a surface-to-surface missile against a ship; or in Taiwan there's a hidden red line by the Chinese, the Taiwanese cross it, and we have a war there; or, of course, something happens with North Korea. This could easily lead us into an escalatory cycle where we have to fight each other. Once the shots have been fired, once people have been killed, domestic audiences get engaged and you're on the march to war.

The other way to think about it is cycles of credibility. Let's say the North Koreans decide to fire off a missile. In order to demonstrate against that, we launch a military strike against them. Well, what are the options? They can continue to escalate, fire more missiles, they can start shelling Seoul, and then we have to escalate as well, and this escalation of risk taking and demonstrations of resolve lead us into conflict as well.

So you think about Mike Pence when he was visiting the Korean demilitarized zone (DMZ), he said, "Look, I want the North Koreans to see American resolve on my face." Leaving aside the fact they probably couldn't see him—and even if they could see him, they probably couldn't interpret what he was doing—it's that kind of perspective or dynamic that can lead us into war in an intentional, sort of credibility-signaling way.

DEVIN STEWART: What would you say is the most explosive or contentious zone in Asia, given what you just said?

RAYMOND KUO: Right now, North Korea. They have had, I think, nine missile tests since the beginning of this year. One of them was a salvo of four, which I think is notable because it's not just "Can our missiles get somewhere?" It's "How do we defeat American and South Korean anti-ballistic missile defenses? We have to launch a lot of them." It seemed like they could probably do that. [Editor's note: This interview took place on June 22, 2017. On July 4, 2017, North Korea launched an intercontinental ballistic missile that some experts believe had the power to reach parts of the United States.]

Plus you have the fact that North Korea is isolated and is led by an unusual leader. I tend to think he's rational, but he is responding to irrational incentives to escalate conflict. Then you also have in the United States someone who doesn't like to be seen as backing down, whose ego gets very quickly involved in these issues. That's just a bad combination when you have two personalistic, ego-driven leaders with their finger on a nuclear button.

DEVIN STEWART: Very unstable.

RAYMOND KUO: Exactly.

DEVIN STEWART: You've talked about resolve, you've talked about credibility, as well as the danger of accidents. What do you make of the "Thucydides Trap" which has been in the news a lot these days? People have been pointing to the danger of essentially when one power is declining and another one is coming up, ascending, and those shifts in power in the international system can create great danger. The Peloponnesian War was seen as a case study in how things can go wrong, and this particular theory of the Thucydides Trap has been promoted by Graham Allison at Harvard. What do you make of that?

RAYMOND KUO: I teach Thucydides in my class. A lot of the lessons that we see from that time do seem to have some parallels with now but with major caveats.

One, Graham's book is an interesting book, but it's surprising that it doesn’t deal more with what's called the "power transition literature," which happened in the 1980s. It was this concern that a rising Soviet Union would overtake the United States and what the United States had to do about it: Should it launch a preemptive war to curtail that from happening? Obviously that didn't happen. There is some question about whether or not that sort of rising power-falling power dynamic actually occurs. In many cases it actually does not. So that's one kind of problem with it.

The second is domestic politics. In a straightforward reading of Thucydides the United States is Sparta; it is the existing falling power. And the Chinese are the Athenians; they are the rising power. But one of the reasons why there was a conflict potentially was the domestic politics. Athens was a democracy; Sparta was an autocracy.

So all of this power transition stuff may just be unnecessary. It's about the fact that China is an autocracy and the United States is a democracy, and so if we really want to have peace, then what we have to do is somehow encourage the Chinese to become more democratic, and we get the democratic peace. So all this stuff about the United States and China, rising and falling powers, is kind of unnecessary.

Finally, there is the issue of honor. In the Peloponnesian War—I think from the movie 300 there's this big emphasis on Spartan honor, and "if you're going to come back, you come back on your shield," I think it was?

DEVIN STEWART: That's right.

RAYMOND KUO: Whereas I don't necessarily think that's the case.

DEVIN STEWART: With China or the United States?

RAYMOND KUO: With both. The caveat to what I'm just saying is the rising nationalism in both countries. But there are good, strong reasons that that's not going to be engaged: bureaucratic incentives, for one, that the people who are actually making the policy or implementing the policy probably don't want this to happen.

Also, coming back to trade, the Chinese and the Americans trade a lot. I think we're the biggest trading relationship in the world. So again, why would you fight about something if you could simply trade over it, or make some sort of side payment or some sort of deal?

For me the biggest issue is—well, during the Obama administration the question was, "How can the United States accommodate a rising China?" And this was in the George W. Bush and Clinton eras as well. And the way they wanted to do that was through international institutions, giving the Chinese a greater say in, for instance, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) so they don't go off and create an alternative structure like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Unfortunately there were a number of people in Congress who said: "No, we can never do that. We can't allow that." So that's exactly what happened.

In Trump's case we have kind of a turning away from institutions. So what do we see? The United States is not trying to incorporate China into being a good actor within the international system, so instead China creates its own institutions: the One Belt One Road Initiative (OBOR), the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which is the alternative to the TPP. And regional states are flocking over to those economic and security organizations instead of to us. It's sort of a ceding of American leadership and allowing the Chinese to kind of fill in a bit of that role—not all of it—in a way that's not helpful for American foreign policy interests.

DEVIN STEWART: Finally, Raymond, what other recommendations would you give to the Trump people to avoid war in Asia-Pacific?

RAYMOND KUO: Easy question. I think first off you have to staff the State Department and many of the other organs of foreign policy in the government. The fact that we do not really have deputy secretaries of state, who are generally the ones who are the workhorses of that department; the fact that we don't seem to have that many in DoD either, or the USTR, or the Commerce Department, all these various organs where we can bring to bear, not just the military power of the United States, but the soft power: diplomacy, culture, economics. Unless we have good people staffing those branches, we're never going to be able to bring together American power and develop and execute a coherent national strategy. It’s just not going to happen.

This is a longshot, but having Trump reengage in international institutions—he doesn’t seem to want to—but the fact that there's been a bipartisan consensus over the benefits of international institutions for 70 years, and that's for a reason—and also trade as well—because we get much more benefit from cooperation than going it all alone.

The difficulty is that cooperation needs a bit of an enforcer, and that's what the United States' role is. The United States is always going to pay a bit more than anybody else, but it also gains enormous benefits from it. We are one of the most open economies in the world; we're certainly the largest economy in the world. We have everything to gain from open trade and having more discussion and dialogue on security matters in different regions.

As part of that, my strong push for him would be to make a NATO in Asia. You have a lot of instability. Asia is generally under-institutionalized as a region compared to, say, Europe, or even Latin America. That means that people don't talk to each other. When an episode flares up in the South China Sea, say, between the Filipinos and the Chinese, how do they contact each other? How can they credibly communicate with each other and deescalate situations? Something like a NATO where you embed states, and dense networks of communication, trade, security discussions, that would really help out the region. It may not include the Chinese, but it would certainly help out with our core allies in the region.

DEVIN STEWART: Who would be in the Asian NATO?

RAYMOND KUO: Japan certainly, South Korea, the Philippines. I would love to see Taiwan in there, but it's probably not going to happen. Singapore possibly.

DEVIN STEWART: Vietnam?

RAYMOND KUO: Could be. I would doubt that though, actually, because the Vietnamese are kind of caught between both the Chinese and the Americans. Certainly the Australians and New Zealand, the Kiwis, would go in there as well.

DEVIN STEWART: Thailand?

RAYMOND KUO: Yes, I think so.

DEVIN STEWART: You don’t think China would be a little nervous?

RAYMOND KUO: Oh, they would absolutely be nervous about it. You have a pretty interesting opportunity right now. You have the United States rebalancing its policies toward military capabilities, which suggests that it has some of the capabilities to help defend these countries. At the same time, the Trump administration is pulling back from its political and economic commitments to these regions.

You can leverage that. You can say, if I'm speaking as Trump, "If you want the United States to reengage in your region,"—say to the Philippines—"then you have to cut a deal with us in terms of trade relations, security relations, boosting your defense spending,"—which is already happening anyway—"and then we will give you this full NATO-like commitment in a region that's the major economic driver for the next century." It's good for the United States because it gets us to reengage; it helps to reduce security problems in that region, and on top of it, appealing just to Trump, it's an easy, low-hanging fruit and deal. I don't want to suggest it's too easy, but it's a nice deal that he could cut and serve a bunch of American interests at the same time.

DEVIN STEWART: Raymond Kuo, professor at Fordham University, thank you so much for coming by.

RAYMOND KUO: Thank you very much.