The Sinai, this crucial land bridge connecting Asia and Africa, has become a haven for transnational crime, fostering arms trafficking, smuggling through the tunnels into Gaza, and Islamic militancy. Courageous Egyptian journalist Mohannad Sabry gives us an inside look at the current situation, both in the Sinai and in Egypt as a whole.

JOANNE MYERS: Good afternoon, everyone. I'm Joanne Myers, and on behalf of the Carnegie Council, I want to thank you all for joining us.

Our guest today is Mohannad Sabry. Mohannad is a freelance journalist who is from Cairo. About nine years ago or so, he became fascinated by the Sinai region and has been reporting on the growth of extremism and official corruption in the Sinai Peninsula ever since. David Ignatius of The Washington Post has said that Mohannad is one of Egypt's best young writers and one of the first to understand the new dangers in the Sinai, observing what so many others have missed. Mohannad will be discussing his book Sinai: Egypt's Linchpin, Gaza's Lifeline, Israel's Nightmare.

This conversation is one of many we have been having recently at the Carnegie Council about a world on fire.

For some time now, Egypt's Sinai Peninsula has been a volatile region from which violent actors have lashed out at Egypt's military and security forces and even civilians. Although the 1979 Egyptian-Israeli Treaty envisioned the Sinai as a buffer zone that would build trust and ensure peace, in recent years this land bridge connecting Asia and Africa has become a haven for transnational crime, fostering arms trafficking, brazen smuggling of goods and people through the tunnels into Gaza, and Islamic militancy. But it is only with the recent downing of the Russian airliner by ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) that the world has suddenly begun focusing its attention on this area, acknowledging just how serious a security problem the Sinai has become.

In the next 25 to 30 minutes, Mohannad and I will have a conversation about the Sinai, about ISIS, about Egypt, and about President el-Sisi that will provide you more information so that you will understand what is happening in this volatile part of the world. Then I will open up the conversation and invite you to ask the questions you have been thinking about.

DiscussionJOANNE MYERS: Let me begin by simply asking you, Mohannad, why does the Sinai matter? Outside of the fact that it is a beautiful tourist attraction, beautiful beaches, Sharm el-Sheikh, what is it about this region that we in the West should be paying attention to?

MOHANNAD SABRY: Thank you very much, Joanne. It is a pleasure to be here at the Carnegie Council. Thank you all for coming. It's great to see that much interest in the Sinai Peninsula and the Middle East region in general.

To simply answer your question, the Sinai is important because it is the connection between Africa and Asia. It happens to be the most crucial part of Egypt, which is the biggest and most vocal country in the Middle East, and it also constitutes importance to all of us. It is bordered by the Suez Canal on the west and the Israeli border and the Gaza Strip on the east. It is the cornerstone of the Camp David peace accords that I believe half the world, especially America, contributed to accomplishing. They have been a stabilizing factor in Egypt's relation with the region around it—with Israel, to begin with, and with the region in general—and have kept partial peace in that region since 1979. This is something that I believe we are all keen on continuing to maintain and to protect.

The tourism industry, of course, is a major element to Egypt on the economic level. It contributes to the economic stability of the country that we all are interested in stabilizing. But most importantly, the Suez Canal is an international investment; it is an international interest. I don't think any country in the world, from Singapore all the way to Canada, is willing to risk or sacrifice the safety and protection of the Suez Canal. Every government in the world that has ships going through the Suez Canal has a very vested interest in stabilizing Egypt in general for that specific point.

Most recently, after 2011, we have seen Arab countries going through uprisings, some of them turning into a state of civil war, such as Libya, on the west of Egypt, and Syria, on the northeastern side. The stability of Egypt here becomes something that is more of an essential element to all of us. It is not a luxury anymore, because we cannot afford another country as big as Egypt and as important as Egypt going into turmoil like any of those countries.

By saying this, I do sound like a lot of people who would say that repression is continuing in Egypt because we want to stabilize it and not turn it into Syria and Iraq, but I do want it clear that I am not coming from that point of view; I am coming from the point of view of a country that has to continue being, hopefully, a stable democracy and a stable, modern country that upholds the ethics and the reform we all aspire to see.

JOANNE MYERS: Why did so many militant groups take root in the Sinai? What was it about this region, what was happening in Cairo that allowed the militants to prosper, so to speak?

MOHANNAD SABRY: We can speak about this from an Egyptian domestic point of view or from a comparative terrorism point of view.

JOANNE MYERS: Let's do both.

MOHANNAD SABRY: Let's do both. In terms of the domestic situation, developments over the past 20 or 30 years in Egypt, the Sinai has remained an area heavily marginalized, left out of development plans, out of national plans. Any region that is normally left without development and without care is also left without proper policing and proper institutional government work. The Sinai happened to be, after the wave of terrorism in the 1990s that flared up all the way to 1997 with the Luxor massacre—

JOANNE MYERS: Are you talking about the Muslim Brotherhood?

MOHANNAD SABRY: I am talking about, not the Muslim Brotherhood per se, but I am talking about the Islamic Jamaat-e-Islami, the Islamic Jamaat, the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, and other smaller groups that were leading the terrorism movement in the 1990s.

In 1997, we all remember the Luxor massacre. After this, Egypt led a massive campaign against the terrorist organizations. A lot of them fled to the Sinai because the Sinai was simply marginalized. There was a desert left unpoliced, untaken-care-of, and open to radical ideologies to spread, open to terrorism that works to start operating and re-recruiting and rebuilding themselves.

Another wave happened, but from the Gaza Strip—and this is the regional comparative terrorism context, the bigger context—when the Hamas government led a crackdown against the jihadist movements in the south. In 2009 we had another wave of jihadists coming from the Gaza Strip taking refuge in the Sinai, which was more lawless. The smuggling tunnels started appearing almost six or seven years after 1997. It became basically a perfectly fertile land for radical ideologies to spread and to evolve and for terrorist networks to start building themselves.

After 2011, Egypt was left without a police department. The police department of Egypt was literally shut down in 2011. The military was fighting to take responsibility for the country on the policing level and on the political governance level. It was a very challenging moment for a military institution that did not operate on the street and should not be operating on the street in terms of general policing.

In comparison to inland Egypt, the Sinai, given its lawless nature and its undeveloped nature, its forgotten nature, became, again, more fertile ground for a terrorist organization to form itself and to build its hierarchy and its ranks and recruit elements and take advantage of the arms trafficking. It continued evolving until we saw the most recent umbrella terrorist group, named now Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis. I would rather call them a group of bloody killers.

JOANNE MYERS: In June and July of 2013, Field Marshal Sisi rode a wave of anti-government protests as the military helped to overthrow the elected president, because Egyptians seemed to be longing for a strong, stable government that would address some of the political and economic problems. But what went wrong? Sisi came in, and now there seems to be repression, sliding back to where you were with Morsi. Could you elaborate on that?

MOHANNAD SABRY: What went wrong is very simple. The move against Mohammed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood was a very anticipated move. If it hadn't happened in July of 2013, it would have happened months later or a couple of years later. It was a very unfortunate experience with an elected president and an elected government. This is why it was extremely popular.

I covered this movement on June 30, July 1, 2, 3, until Mohammed Morsi was toppled. I saw how popular this move against the Muslim Brotherhood was. I can confidently say that the majority of revolutionary figures, movements, youth movements, democratic, liberal, politically active organizations were hoping that this move would get us back to the democratic process where you can have open elections, the military could just protect the country in a phase of turmoil, where people were shooting each other on the street. There were massive armed crimes.

Unfortunately, what went wrong is that the military decided to continue down a political path, and President Sisi decided to go from defense minister—a celebrated defense minister that took the side of the people—to the position of the sole candidate who crushed any other opportunity for candidates, and the repression continued.

As you said, we have seen the same people who have taken to the street on June 30 against Mohammed Morsi, against the Muslim Brotherhood regime, are thrown into jails now. The repression is reaching unprecedented levels. This is simply, for so many reasons—I don't think we have the time to discuss all of them—because the road was not open for an open democracy and equal opportunity for candidates and for the democratic process to continue.

JOANNE MYERS: What was lacking?

MOHANNAD SABRY: I think what was lacking was the will to understand that before 2011 we had 10 years of protests on the street in Cairo under Hosni Mubarak, under the severe repression and crackdowns of Hosni Mubarak, until 2011 when it toppled him and forced him to resign. What was lacking was understanding that the wheels of history don't go back; they go forward. The fact that the Egyptians had in 2011 succeeded to a level of forcing a 30-year immune dictator to resign is a development that will not reverse. Egyptians will continue, no matter how much they are thrown in jail, how much they are suppressed, their freedoms shut down, they will continue aspiring for that movement that they began in 2011 and worked for for 10 years before that. It is a successful step that they have taken. Success always leads to more aspirations and more ambitions.

I think that the simple lack of understanding that reform has become essential—not a luxury, not a street demand, but essential—for the stability of the country, for the country to move forward, and for a country like Egypt to become a real modern power within a region of turmoil and civil wars and terrorist organizations—the regime, the entire Egyptian society, including the government, the institutions, the police, the military, all of us, have to understand that it is time for us to all accept reform, and some of us will have to pay the price for this reform—mainly the ones who oppose it.

JOANNE MYERS: It seems that the internal politics and security remain largely under media blackout. What is Sisi afraid of?

MOHANNAD SABRY: Are you speaking in terms of Egypt or in terms of Sinai?

JOANNE MYERS: In terms of Egypt and the Sinai. Sinai is part of Egypt, right? You have called Sinai the linchpin of Egypt. I would like to discuss that, too, why you call it the linchpin.

MOHANNAD SABRY: It is the linchpin for all the reasons that we started the conversation with. It is the linchpin because, simply, the Sinai was the field of Egypt's wars. It was the field through which armies moved east and west, either armies coming to invade Egypt or armies coming out of Egypt during the Ottoman Empire. It is the linchpin because if you look at every effective subject or incident that affects the whole national security of the country, you realize that it is connected somehow to the Sinai Peninsula, for so many reasons, including everything that we have discussed—its importance, its lack of proper governance, its lack of care, and all of this. The same applies to the arms trafficking route, which goes all the way from Africa into the Sinai, mainly through the Gaza Strip.

JOANNE MYERS: And human trafficking, too.

MOHANNAD SABRY: Human trafficking, drug trafficking, organized crime, criminal cartels, cross-border criminal cartels, and so on and so forth. It is also, understandably, the region that sparked many wars between Egypt and other countries. Most recently, it was the Suez Canal, bordering the Sinai, that sparked the war in 1956, and it is the Sinai and shutting down the Aqaba Gulf that sparked the 1967 war.

JOANNE MYERS: Just going back to the media blackout, what is Sisi afraid of? Why did he come down so hard on the media and journalists like you?

MOHANNAD SABRY: Let me answer with the Sinai first, because it is a part of Egypt, of course. It is a very beloved part of Egypt for me. But it is a special case. The Sinai has come to an unprecedented point of being a troubled region. The state is barely containing the situation in the Sinai. We continue to see the terrorism flaring up and continuing, the terrorist attacks. The repression has also reached unprecedented levels in Sinai. The collateral damage of the military campaign has reached very high levels.

We have the similar mentality of governing the country, thinking that the best way of just doing our job and continuing with it is just to black out this region and shut down access, basically, which is why, if you try to read in the Sinai, you will find very few informed sources. Most of the time we would not get the full story. It is impossible.

Someone like myself who specializes in the subject—I spent so much time in the Sinai—I cannot go back to the Sinai now because it has become lethal. We also have the threat from the militant organizations and terrorists, who don't like us to be there, don't want us to see what they are doing, as well—

JOANNE MYERS: What are they doing that they don't want you to see?

MOHANNAD SABRY: Our presence as journalists, as investigative reporters, is something that continues the monitoring wheel to turn. That monitoring constitutes fear for the terrorists, who don't want us to be there—

JOANNE MYERS: How big a threat is ISIS in that area? I mean, they just shot down the Russian plane.

MOHANNAD SABRY: They have committed unprecedented terrorist attacks in the history of Egypt. They have infiltrated the security core several times. They have killed very-high-up officers in the security and the military institution. They also target people like us, who would criticize them, of course. They target the community in general. They also use the element of fear against the community as much as the institutions are using the element of fear against the community.

JOANNE MYERS: Is el-Sisi right, then, to crack down on these militants?

MOHANNAD SABRY: Of course he is right to crack down on them, but those crackdowns have another term called counterterrorism. We have security operations. We have whole security sciences, decades of security sciences, especially in counterterrorism, that should be deployed and should be used. Also, the idea of collective punishment and the idea of the excessive use of force and the reckless use of force and getting to a point of not caring about the collateral damage and how that crackdown would reflect in the community is simply worsening the situation rather than resolving it. This is why we have a blackout continuing all the time.

Speaking of the blackout, just yesterday a colleague of ours called Ismail Iskandarani, who is also a Sinai researcher, whom have I met several times in the Sinai, at times when people would not go to the Sinai—he just landed in Egypt yesterday at Hurghada Airport, to be arrested by state security and referred to prosecution on charges of joining a terrorist organization and spreading false rumors that destabilize national security. This is a prime example of crackdowns on the media and shutting down the access to all of those stories around the country.

JOANNE MYERS: For a long time now, Egypt has taken a backseat in Middle Eastern politics. How do you see it reasserting itself on the regional and the world stage if it is repressing all this media and attacks and whatever?

MOHANNAD SABRY: Despite the fact that Egypt has taken quite a backseat, we also can see the international and the regional interest in Egypt's stability and in cooperating with Egypt. We see that coming from the Gulf countries, we see that coming from North Africa, and we see it coming from the world in general.

But we have to understand that Egypt would not be able to take the front leading seat that it took for decades without actually resolving its internal issues and becoming a stable power. You cannot claim that you will be a solution for Libya's security problems if you cannot contain the security problems that you have domestically. Those are issues that drain the country's economy, drain the country's time and effort. Simply, you cannot offer help to other communities if you are incapable of helping your own community or stabilizing your institutions or upholding fair and proper attitudes and tactics and policies within your own community.

This is why we again have to stress that the stability of Egypt and the reform in Egypt—and reform in every level, from the press freedom to the human rights, to the political arena—it has become an essential element of Egypt's development rather than just a demand by the opposition.

JOANNE MYERS: Do you think this will happen under el-Sisi? Are you optimistic?

MOHANNAD SABRY: I'm always optimistic. I have survived doing this. We all do our job, and we have to all be optimistic, because there is always a solution for everything. The solutions are not as difficult and not as crazy as the Egyptian regime would like to see them.

But what we lack for those solutions to be applied is the will to reform. The will to reform is very costly.

JOANNE MYERS: But the people have the will to reform. That is what is needed, for the civil society to develop and take root. If the people have the will, what will happen next?

MOHANNAD SABRY: The people do have the will—a lot of the people do have the will—but you also have a portion of the community who was happy under Mubarak, who was happy under other dictatorships, and they don't really find it an essential matter.

Also, as I was just saying, the reform has a very heavy price to be paid for it to be accomplished. That heavy price mainly is paid by the institutions that have to be reformed. If we are talking about, last week, four cases of death under torture in Egypt—and that is just last week—this tells us that there is a police department that has to be reformed. For that reform to happen, people will have to be held accountable. They will have to stand trial for what they have done, and they will have to pay a very heavy price and be made an example for others not to continue doing the same thing, which has been continuing for decades.

JOANNE MYERS: But is the judiciary corrupt, then? Where do you see the judiciary?

MOHANNAD SABRY: The term "corrupt" is a very difficult term to use. It is a very heavy claim. It is a very dangerous claim that has to be backed up with a lot of evidence. But I can say that there is a lot of politicization of government institutions, including the judiciary. There is a tendency for every leading institution in the Egyptian regime to continue endorsing each other, no matter how wrong or right they are, for the whole regime to continue going down the same path it is going.

JOANNE MYERS: But the judiciary has made some progress. They released the Al Jazeera journalists recently. That is some progress, right?

MOHANNAD SABRY: And the state security just detained another person, the last in a long line of—

JOANNE MYERS: So it is one let go, one in and one out?

MOHANNAD SABRY: It is actually, I would say, one out for 100 in. The judiciary has released Mohamed Fahmy and Peter Greste and Baher Mohamed, who were all colleagues and good people, and they should not have been in jail in the first place. But they released them after 400 days and a farce trial. It cost the country, on the political level and the economic level, so much that it could have just saved us all the embarrassment, the international embarrassment, and saved the government itself the trouble that they have been through, for this specific reason.

Did the judiciary interfere to fix that situation? Absolutely not. It actually enforced the idea of keeping them in jail for 400 days, on a completely trumped-up charge, and even the evidence was a joke. If you all followed the story, you would remember that when the court was viewing the alleged evidence, some of that evidence was a video clip of a song of a very famous singer. The judiciary did not stop this scandal that went on for a year and a half or something—more than a year and a half.

Nowadays, we are facing a situation in Egypt where you have hundreds of political prisoners, some of the most leading revolutionary youth figures of Egypt, that went out in 2011 calling for reform, that brought us to the point of democracy where we had free and fair elections, no matter what happened to it after that. But we at least got to this point, and we got to this point only because those youths put themselves on the line, put their lives on the line, and took the risk under one of the world's ruthless dictatorships, Hosni Mubarak's dictatorship, and they accomplished what they accomplished. Now, if you look at where they are, they are thrown in jail.

The example of yesterday is another one, where a journalist like myself, like my colleagues—and I believe December is the annual report time for press freedom organizations, and we are bracing for very embarrassing reports about the state of press freedom in Egypt.

JOANNE MYERS: So what do you think is the best way for the West to engage with Egypt?

MOHANNAD SABRY: I think the West is already engaging with Egypt. I think the West understands the importance of Egypt's share in international issues and in facing international issues. I believe that the most urgent issue to engage with Egypt on is the issue of security, because Egypt is infected with a terrorist organization that continues to operate. There are so many other levels. I believe that the West continues to try to talk Egypt into reform, especially on the human rights level.

We are sitting in the United States, in the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, and we are in a country that hands Egypt military aid, a massive amount of military aid, every year. This comes back to the United States with a lot of criticism, with a lot of questions about its relation with Egypt. I believe the U.S. government is trying to work with Egypt on the Sinai, the most crucial and most hostile part of the country currently. Are they scoring any success? Unfortunately, we have no way of knowing this, until we see success or failure.

JOANNE MYERS: If you could pick out one or two principles, which would you say are the most important to help Egypt going forward, as a guiding principle?

MOHANNAD SABRY: One or two?

JOANNE MYERS: One or two. You can pick more—three, four.

MOHANNAD SABRY: I can bring out the list.

JOANNE MYERS: I just would like to hear from you, being there.

MOHANNAD SABRY: I am not going to pick one or two, but I would say that I think we have to start understanding and admitting to ourselves that human rights and fighting corruption are not something that you do because you are nice. No. It's something that you do because it helps your country flourish, it helps your economy stabilize, and it helps you make more money, if what you are looking for is money. It helps you make a better reputation, if what you are looking for is a better reputation.

This is, unfortunately, what those officers in the police department who kill people under torture, and the heads of those officers who don't hold them accountable and send them straight to trial—this is the point that they don't really understand. They don't understand that, actually, reform is going to protect you, reform is going to make your life much, much better and is going to relieve you from the headache of having to deal with the opposition all the time. The more you apply the reform, the less headache you get from the opposition. It is a simple experience that the whole world has gone through for so many decades. Unfortunately, we are still fighting to go through that.

JOANNE MYERS: Hopefully, Sisi is listening at some level and he will initiate some of the reforms and take to heart some of the suggestions you have.

QuestionsQUESTION: Don Simmons.

Just two economic questions. My recollection is that a sizable portion of Egypt's oil production and reserves is in the Sinai. Is that right? If so, how significant are those reserves?

Secondly, the Suez Canal, I think, has just opened an enlargement that now lets northbound and southbound ships pass each other in the middle of the transit. How important is that economically? Does that look like a successful investment?

MOHANNAD SABRY: The oil reserves—I am not an oil specialist, and I am not an economist. I hope to become one someday, but I am not there yet. There is a massive oil industry in the Sinai Peninsula on the eastern Mediterranean, right off the coast of northern Sinai and in the Suez and Aqaba Gulf down in the south—mainly the Suez Gulf.

Are they major? Egypt is not known for having major reserves of oil. We are a country that continues to import oil to cover its deficit every day pretty much. Nowadays, given the lack of access, again we cannot really put our hands on the actual numbers: What does our deficit come to? What is happening with the oil sector specifically?

The oil sector has gone through a lot of corruption scandals over the last 10 years of Hosni Mubarak. We all remember the gas pipeline to Israel and the story of selling Egyptian gas for lower than international prices. All of that has to be tackled and approached.

As for the new Suez Canal, I will tell you simply what I was told by experts in the ports industry in various countries. The Suez Canal project could be a $100 billion project or it could be a nothing project. To be a $100 billion project, it has to turn from just a naval passage into a port hub, into a mother port, such as the examples that we see in Singapore, that we see right beside us in the Emirates and Jebel Ali and so on and so forth.

Are we working to build this, to create this in Egypt? Are we capable of doing this on our own or with other countries? Again, the Egyptian regime, the current regime, has made so many economic promises over the past two years and nothing has been accomplished. I think the Suez Canal so far has cost us billions of dollars that we can't really afford, and we are not seeing the return yet. Hopefully we will get to a point of world business standards that will give us an opportunity to turn that Suez Canal into a source of income that Egypt never had and direly needs. Still, we're being hopeful.

QUESTION: Susan Gitelson.

To follow up on the economic side, what is happening with tourism since there was a recent problem with Sharm el-Sheikh and the Russians?

To what extent can the government control the smuggling for the Gaza Strip?

We have had many fascinating conversations about the need for jobs—for youth especially, but for everyone—in productive industries, and people who are being trained in the universities or whatever, with professional degrees and unable to find employment and being very upset, and sometimes going into terrorism and so forth. Please address some of these issues.

MOHANNAD SABRY: As for the tourism sector, unfortunately—and I have a lot of friends working in the tourism sector—they are scoring losses continuously since 2011. I believe Egyptian state-owned newspapers just reported today that the losses of the South Sinai tourism sector have reached $2 billion and continues to count.

It is understandable. We had Mexican tourists killed in the Western Desert several weeks ago. Right after that—we hadn't finished that story yet and we get the Russian airliner crashing in the Sinai. But we also have to understand that Egypt's tourism sector is very fragile. It is very fragile because of the nature of that sector, but it is also very fragile because we do not take the proper care of the tourism sector.

One simple example that I believe I reported on in 2012 is someone who owns a beach camp in South Sinai, which is the kind of tourism there, scoring losses all the time, and at the end of the year, he gets a letter from the government asking him for 50,000 [Egyptian] pounds in taxes. This is what, again, the state has to do to contain those losses and to try to promote local tourism instead of the foreign tourism that would not pretty much arrive because of the security situation.

The security policies that are being applied are being applied regardless of how they reflect on other sectors, the economic sector or the tourism sector. South Sinai, for example, since the unfortunate death of the Mexican tourists—the Egyptian regime just decided to ban the use of SUVs all over the Western Desert and the Sinai. Those are desert areas, and 50 percent of the tourism in those areas is desert tourism, besides the beach tourism. Again, this was a security policy just passed and signed off by a higher officer without really having any regard for the effect of that on the tourism industry that is already reeling.

As for jobs for the youth, this falls under the greater category of reform. I don't think any of us would get a job without having a stable, proper, flourishing economy, and an economy that fights corruption and provides equal opportunities rather than providing an opportunity for who has the connection or who has the money and so on and so forth.

Just two days ago, we saw the Egyptian graduates who have a Master's degree and a Ph.D. degree protesting in Tahrir Square asking for a job. They are unemployed, despite their higher education. This happens right beside my house, where I live in downtown Cairo, every year. The reaction is, again, every year a crackdown on them, using central security riot police, rather than actually bringing those people in and incubating them and trying to incorporate them in the reform and the effort to strengthen the economy and provide more jobs.

QUESTIONER: And what about the Gaza smuggling?

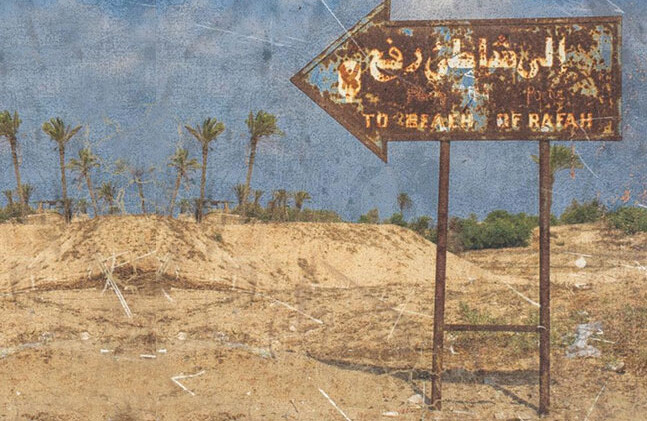

MOHANNAD SABRY: Finally, Egypt has taken positive efforts towards the smuggling tunnels. The vast majority of those tunnels, the overwhelming majority of those tunnels, are completely shut down. But to do this, we, unfortunately, had to evacuate and level a historic town, Rafah, one of the most historic towns in the world. This reflected on the population very, very negatively.

It also takes us into a more complicated part of the story, where Egypt has left the economy in Sinai to go into the blacker side of the smuggling economy, rather than providing jobs and factories and companies and farms. Now, all of a sudden, you decide to shut down the black economy that you have allowed for decades, and you have left the region of North Sinai without black or legal economy.

So you are left in a situation where you have thousands of families, thousands of people, who were getting profits out of the larger smuggling industry, and now all of those are left without a job. Added to that, their houses have been leveled. They have been compensated by the government, but it is not as simple as giving someone a little bit of money. It is a very complicated situation, especially when you have a terrorist organization sitting right next door to this population trying to recruit as many of them as possible. It becomes a story that you have to investigate. You have to put much, much more effort than just signing off on an order to level the city of Rafah or shut down the tunnels and so on and so forth.

It extends the regional geopolitical extension into the Gaza Strip. The economic situation in the Gaza Strip is extremely dire, especially after the 2014 war. Neither the tunnels are helping fix that, because the tunnels are shut down, nor the border terminals are helping fix that. This reflects in Egypt and Israel very negatively in terms of the stability of the Gaza Strip, the security, and the continuous explosions and boil-overs of the Gaza Strip into the country's border.

JOANNE MYERS: Do you see the Bedouins there as part of the problem or part of the solution?

MOHANNAD SABRY: I think that the population is always a part of the solution. I think that the population is always the solution. The reason why in North Sinai you have some of the most successful agricultural industries—up until the military campaign started and pretty much disappeared the majority of that—the population is always an opportunity for any system to create a solution, to create a legal functioning environment.

The Bedouin community is a very promising community. It has always been like this. It is a proud community with thousands of years of history, of tradition, of customs, and they have proven themselves over and over. They have proven themselves to be loyal to their homeland. They have proven themselves to be keen on having a job, a legal job, rather than being a smuggler, and it is in this example where someone would go work in the smuggling industry for a year to make a few hundred thousand pounds or a few thousand pounds, and the next thing they do is go start a farm or start a fish farm.

This tells us that this community is not, as we tend to view all the time, naturally born bandits. No, they are not. They are humans. If you give them an opportunity to become a clean community and succeed and prove themselves, they will do it. But if you continue to outlaw them, to force them into becoming bandits and to tag them as terrorists, they will simply become that. Fortunately, we are seeing very minimal signs of that, where the younger, angry, the simply marginalized youth are being tracked down by the terrorist organizations for recruitment. Some of them fall for it; a lot of them don't, fortunately. But it is an urgent matter that we have to start taking care of.

JOANNE MYERS: These ISIS members, do they come from outside the region or are they homegrown in the Sinai?

MOHANNAD SABRY: It is a domestic Egyptian, endemic terrorist organization. We tend to turn it into conspiracy theory, made by this and that, foreign powers that are conspiring against us. But, simply, Egypt is a country that has suffered domestic terrorism for years, and unfortunately this is another wave. Some of them are Bedouins. Some of them are local Egyptians from the Nile Valley. Some of them are from the Gaza Strip.

But again, when it comes to terrorism, I don't care what the nationality is. Whoever straps that explosive belt on himself and goes and kills civilians is simply a terrorist, no matter what their nationality, color, or religion is.

QUESTION: Youssef Rafiya [phonetic].

Away from tourism and terrorism. Ethiopia has been building the Grand Renaissance Dam. How big of a threat is that to Egypt? What has been the domestic view of that dam being constructed in Ethiopia? Is it actually going to affect Egypt at all?

MOHANNAD SABRY: I'm sorry, I have had very little time to follow this story. What I can say is that I have great Ethiopian friends. I love Ethiopian food. I hope it is not a threat to Egypt and I hope we seriously come to a roundtable discussion rather than just throwing insults at each other in newspaper pages. I think that two countries in Africa the size of Egypt and Ethiopia have much more capability of resolving such an issue in a very respectable and objective manner, a productive manner, rather than just leaving it until it becomes a greater issue.

QUESTION: Good evening. Philip Schlussel.

Can you comment on the popularity of the Sisi government in Egypt?

MOHANNAD SABRY: The Sisi government is popular among a lot of the Egyptian population, big parts of the Egyptian population, but it is very unpopular among other parts of the Egyptian population. I think that we are seeing more of that lack of popularity coming to the surface simply because popularity is something that you build, that you build with credibility, with offering what you can and what you have to offer, and simply continuing to own up to your promises.

We are facing a regime that—again, I will take you back to a very simple example of death under torture. One of the relatives of the people who died in a police station came out on television, publicly on the air, which was exceptional, and simply said to the presenter, "The only thing that would satisfy me is for whoever killed my son to face the same fate." She said publicly on television, "I voted for Sisi, and now his police department killed my relative." I believe this was either her brother or her son. To see one of the voters that voted this regime into power come out on television as a victim of the same regime, this tells us something.

JOANNE MYERS: Do you think Sisi has aggravated rather than increased the security, made the situation worse?

MOHANNAD SABRY: I think that it is a good sign that President Sisi has acknowledged those problems in many instances. He has acknowledged the Sinai in one or two instances, which is absolutely not enough for the numbers of losses that are inflicted in the community. But he has acknowledged that there are mistakes and they have to be fixed. But then again, it is not about acknowledging them. It is not about paying a visit to someone or appearing in the media. It is about the actual policies that are applied, the actual reform that is applied, and, first and above all, upholding the law. If the people who are supposed to uphold the law are the first ones to break the law, then what do you expect from ordinary people in the street?

JOANNE MYERS: Shway, shway. Is that what they say? Slowly, slowly.

MOHANNAD SABRY: I believe it is a gradual change that we are talking about, that we are discussing. It is never overnight. But there is always a starting point and there are always good signs that continue to give the population the patience it requires for them to wait for that reform to be applied. As long as we don't see those signals loud and clear out there, that is a very bad sign.

QUESTION: I'm Jonathan Cristol, from the World Policy Institute and Bard College.

I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about the relationship between the Israeli military and the Egyptian military in Sinai, as well as the intelligence communities, and maybe Israel allowing the Egyptian military to operate more freely closer to the border than what is allowed under Camp David.

MOHANNAD SABRY: I don't really have to say anything new about this, because the Israeli press and the Israeli community has voiced its happiness with the fact that the security coordination between the Egyptian military and the Israeli military is at its best in the past decades. I wouldn't say Israel allowed Egypt to bring in troops. This peace accord also has a security coordination process applied, and this allows both sides to move troops, with the consent of the other side, into the demilitarized zones. Israel also has a demilitarized zone on its border. The fact that those troops moved in is a good sign that we are not as rigid and as bureaucratic about everything around us as we used to be, because you cannot expect Egypt to fight terrorism in Sinai without moving troops in.

Has this collective effort led to a better result? So far we are seeing good results and very bad incidents at the same time. Is it crucial? I think we cannot say this because we have no idea what kind of cooperation is happening. Is it just cooperation in terms of intelligence? Is it in terms of border security? We have no idea. Both sides don't want all of us to have access to that story.

QUESTION: Ed Albrecht, from Mercy College.

I have a question regarding the evolution of the relationship between Egypt and Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries. I know Saudi Arabia has invested heavily in the agricultural sector in Egypt to feed its growing population.

At the same time, I am also wondering, what is the evolution of the relationship between Egypt and Turkey, especially after the fall of the Morsi government?

MOHANNAD SABRY: We have all seen the fruits of this evolving relationship between Egypt and specific Gulf countries, namely Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. They have supported Egypt economically to a great extent. They have pushed massive amounts of money into the Egyptian economy to take it out of its troubled times two years ago.

The investments—we continue to hear that there are projects starting, but again it is the same answer that applied to two other questions: that we are not really seeing the effect of those economic projects on the community in general or on the economy at large. Such projects take time. I don't expect them to start making profits, massive profits, off farms or heavy industries overnight. Those projects take years.

But I believe that also Egypt has the capability in every essential matter to starts its own domestic projects. It is relying heavily on the foreign investments rather than just allowing projects to be created or encouraging local projects to be created—namely in the Sinai. The Sinai is a region where it is in dire need of economic development. A lot of people are willing to start investing locally in their communities, but, for so many reasons—and the top reason is the security situation, the security crackdown, Operation Sinai—it keeps this from happening.

The cooperation with the Gulf countries, the relation with the Gulf countries, is changing, because the local policies of the Gulf countries continue to change in their own track back in those countries. How that will affect that relationship we are not sure, but we are seeing it influencing that relationship. The money from the Gulf I believe has stopped to a certain extent. The investments might continue, but the billions of dollars that were coming in have stopped. Some of what was promised is not coming in.

For a country like Egypt, you cannot rely on foreign grants or foreign help. It is a country of 19 million people that has to operate independently and be capable on its own to handle those issues independently.

The relationship with Turkey: I think the relationship with Turkey is the same. I think it has been standing still since the toppling of Morsi. Both governments don't really prefer each other. They continue to have their continuous state of facing off with each other every time they have an opportunity to do that.

Turkey is endorsing heavily one party of those disputing in Egypt domestically. I am not evaluating or commenting on that, but this creates complications in the relations between those two countries, reflected in the economy, where a lot of Turkish investments have left Egypt for the past few years and even before that. Millions of dollars in promised investment did not come since Mohamed Morsi was toppled.

JOANNE MYERS: If there are no more questions, I would like to thank you very much for telling us about the Sinai.