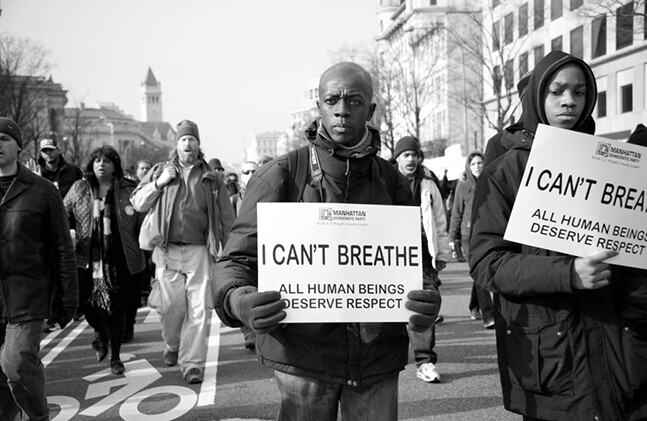

As we entered the last few months of 2014, national and local media outlets alike began to publish calls for a national 'truth and reconciliation commission' (TRC) for the United States in response to the racialized violence that grabbed the country's attention. The exoneration of the policemen responsible for the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York, catalyzed discussions nationwide over race relations in the United States. Amongst the many opinion polls the message has certainly become clear: Americans are not living in a post-racial era. This can be seen in a recent poll commissioned by NBC and The Wall Street Journal where 57 percent of the country considered race relations as 'bad,' while a quarter considered them 'very bad.' Even more noteworthy, a recent Gallup Poll revealed that 13 percent of Americans believed that race relations/racism is the most important problem facing the United States—which Gallup noted has not been as high since the LA riots in 1992. On the face of it then, a TRC process—something that appears to offer both the promise of beginning an honest discussion on race relations in the United States, and the potential for reconciliation in its aftermath—seems like an obvious solution. What many authors have overlooked, however, is what an American TRC would actually look like and whether or not such a model could indeed be tailored to fit the circumstances of the United States.

The TRC Model

The TRC model has continuously evolved since it took the form of the fact-finding, non-judicial truth commissions seen throughout Latin America in the 1970s and 1980s. The purpose of these commissions was to uncover the abuses committed by dictatorships and military juntas, whilst also establishing a more inclusive and representative narrative of history for the country at hand. During the 1990s, more countries in Latin America and Africa saw a need to complement the truth-seeking process with one of reconciliation after periods of inter-group conflict and political transition. In the media discussion that has already taken place about a national TRC for the United States, commentators have seemed to suggest that America replicate the TRC model used in South Africa as that country transitioned out of apartheid. The South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission remains the most renowned and has been replicated dozens of times as a way of helping countries transition from an era of state-wide violence and division to a more peaceful status quo. At first glance the South African process, with its focus on transforming race relations in a nationwide context, might seem an obvious model upon which to base an American process that has similar aims. However, even suggesting a national TRC for the United States, without first recognizing the unprecedented nature of such a mechanism for the country and how it would work, could result in a fruitless discussion.

South Africa: A Model Approach?

The South African TRC is widely praised for its emphasis upon restorative justice. Unlike previous truth commissions in Latin America, it did not offer widespread amnesty to perpetrators, but instead enticed them to come forward and admit their guilt in exchange for amnesty case-by-case. The TRC formed committees that ensured that both rehabilitation and reparations would be provided on an individual basis. Live broadcasts of South Africans—black, white, Indian, and colored1—testifying before the commissioners in a court-like setup were shown internationally. It was not long before the world, and most importantly South Africans, came to learn of the many hidden atrocities that had been endured under the apartheid system. There is no doubt that the South African TRC process has resulted in a model of public reconciliation which deserves attention from all areas of the globe, including those in the United States who are searching for a mechanism to ameliorate a legacy of systemic racism. However, it is essential to recognize that the South African TRC favored an individualized approach that placed victims and perpetrators at the center of the process, rather than the apartheid system and its structures of governance, and that this framing may limit the applicability of the South African model to other settings.

As Mahmood Mamdani points out, although the South African TRC labeled apartheid as a "crime against humanity," it did not formally address the system of apartheid and its legality, but rather the individuals who were affected by it.2 In other words, although the TRC was branded as a national activity, in reality its focus upon 'victims' and 'perpetrators' individualized the process of reconciliation and allowed the system of apartheid, and those who worked within it, to remain in the shadows, hidden from scrutiny. Any TRC model that bypasses the role of institutions and structures of governance and focuses only on individuals is going to be heavily flawed if it is deployed to address structural racism in the United States. The South African TRC model, which individualizes the process of reconciliation after racialized and ethnicized violence, has extreme shortcomings when applied to a North American setting in which institutions, as well as individual actions, must take center stage.

Canada's Truth and Reconciliation Process

The United States need not look far for a country that chose to establish a national truth and reconciliation commission that is currently examining historic racist violence against its indigenous peoples. The Canadian TRC model is a unique process: it is the first to be taking place in a society not undergoing fundamental government transition, as seen with the rest of TRCs. In this, at least, it offers the United States a basis for comparison. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada began its work in 2009 and is focused on the Indian Residential School (IRS) system and the abuses perpetrated by the church- and government-run institutions against First Nations, Métis,3 and Inuit children. The Canadian TRC model, like South Africa's, can be characterized as very top-down, confined as it is to a mandate that results from the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement, a lawsuit settlement reached between the Canadian government, the Counsel of the Churches that ran the schools, the Assembly of First Nations, Aboriginal Peoples organizations, and IRS survivors. The Canadian TRC has treated the IRS system, much like South Africa and apartheid, as a crime against humanity and has not been shy to label the system as one that perpetuated cultural genocide. At the same time, however, it repeats the same mistake: the structures of governance that created the IRS system have not been critically examined.

Moreover, the IRS system is individualized as an isolated occurrence, and thus separated from other anti-Aboriginal policies both before and after the IRS system was in operation. In the same spirit, it has engaged First Nations and Inuit communities on a case-by-case basis, compartmentalizing the process as opposed to allowing the communities to lead the process themselves in a more culturally and historically nuanced way. Again, this is not to say that the Canadian process is fatally flawed. The acknowledgement of the abuses that took place in the IRS system is an important first step to an improved relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities. The problem that remains is that the majority white, non-Aboriginal populace has been largely disengaged from the process—something that could also be detrimental to an American process, if this model were adopted in the United States. Additionally, the way in which the TRC emerged—from a legal process that required it, rather than a community that led it—raises questions about the political will that exists to continue wider reconciliation efforts after the Canadian TRC's mandate expires in June 2015. The Canadian TRC offers significant lessons from which the United States can learn. Yet in fact, there may be no better lessons than those already learned within its own borders.

Greensboro: A Grassroots TRC

The South African model has inspired a range of top-down approaches, but in recent years the flaws in that model have led to alternative interpretations of addressing issues of community division, models that both offer lessons for, and an alternative approach to, an American truth and reconciliation process. The first TRC to operate within the United States was the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission in North Carolina. On November 3, 1979, in Greensboro, local Ku Klux Klan and Nazi Party members ambushed a coalition of racial and economic justice protestors, killing and wounding a number of them. Using a model that broke away from the top-down model of the South African TRC, the TRC in Greensboro was initiated and led by local civil society organizations and Greensboro residents to address the lasting effects of the massacre and the multiple exonerations, by all-white juries, of the KKK and Nazi Party members involved, as well as policemen who had the knowledge to prevent the massacre. The Greensboro TRC was successful in bringing the perpetrators, the survivors, and the victims' families into public forums to recount the events of that day, at the same time allowing the presence of systematic and societal racism to be discussed in the open. However, despite the many positive aspects of the Greensboro process, at the end of the day its recommendations fell on deaf ears. Although the TRC sought the support of the city of Greensboro, ultimately the predominantly white City Council rejected the TRC process and the commission's 500-page report—in the end, only offering a statement of regret. Greensboro's attempted TRC process offers a reminder that to have any hope of instituting long-term change, a TRC mechanism or process needs local government actors to commit to the changes necessary. Only then will the institutionalized aspects of abuse have any hope of being addressed. However, the process of obtaining such commitment, especially when it comes at a potential cost to those in power, is much easier said than done. A TRC in Maine has nevertheless endeavored to experiment with this prospect.

The Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare TRC: A Possibility

In 2012, the state of Maine and the Wabanaki tribal governments located within its boundaries (Houlton Band of Maliseets, the Passamaquoddy at Sipayik and Motahkomikuk, the Aroostook Band of Micmacs, and the Penobscot Nation), signed on to a joint tribal-state TRC that was designed at the grassroots, creating a hybrid TRC model. The Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission (MWTRC) has been specifically mandated to investigate and document an era in the state's history that saw Native children being sent into foster care at an alarmingly high rate, calling into question the state's adherence to the federal Indian Child Welfare Act. This process is unique in that it is the first government-endorsed TRC in the United States and it is also, as Eduardo Gonzalez of the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) recognizes, "trying to throw light over issues of marginalization, and discrimination, to cast some light on race relations in the state of Maine."

Learning lessons from the TRCs in South Africa, Canada, and Greensboro, the MWTRC has managed to pioneer a very different model. Like South Africa, the MWTRC drafted its mandate and formed a commission, in this case to inquire into the forced removal of Native children and those affected during the process, while also (unlike South Africa) placing the state and its child welfare system under examination. The truth-telling and healing mechanisms of the MWTRC are very similar to those seen in the Canadian TRC process, such as sharing circles and private testimony. The MWTRC also seeks out to change child welfare practices fundamentally and seeks systemic reconciliation between the child welfare practices of the state and those of the tribes, all of which will be outlined in its recommendations to the tribal and state governments at the conclusion of its mandate in June 2015.

Learning from Greensboro, the MWTRC obtained the signatures of the five tribal governments and the state of Maine, and, like Greensboro, also formed an organization (i.e. Maine Wabanaki REACH) to help fulfill the specific and wider goals of the TRC within and beyond its mandate. The MWTRC operates within the whitest state in the United States and has a relatively small Native population in comparison to other states. Yet it has managed to engage both Native and non-Native populations; being both very responsive to the needs of tribal communities and having the wherewithal to navigate non-Native networks within one of the more sparsely populated and geographically isolated states of the east coast. However, it still lacks widespread understanding in the state amongst the non-Native population, and the grassroots nature of the MWTRC, like Greensboro, has resulted in funding challenges. Nevertheless, the MWTRC may provide the most innovative model for others in the country, and indeed the world, to replicate and adapt accordingly.

Arguing for an American Truth and Reconciliation Process

The evolution of the TRC model—from the shores of Cape Town, South Africa to those of Portland, Maine—has much to teach the architects of a truth and reconciliation process across the United States, should such an idea ever come to fruition. First, the government needs to be placed under a lens of examination. South Africa and Canada have emphasized the provision of healing and restorative justice measures for individuals, while the governments that instituted the oppressive structures and policies are not under the same level of examination. The structures and policies of apartheid, and of the political "expediency" that resulted in Indian Residential Schools, created an environment in which abuses were sanctioned. Commenting on and making the necessary modifications to the structures that permitted marginalization and, in many cases, dehumanization, is a step towards long-term reconciliation.

Second, a truth and reconciliation process in the United States should recognize the very diverse nature of the country's fabric. An American TRC cannot just address a single crime or a single group; there must be an inclusive conversation. It is important to note that seeking to define truth and reconciliation is one of the toughest challenges for a truth and reconciliation commission, or similar process. It is a largely subjective and sensitive undertaking that many times has been taken hold of by the government instead of communities themselves. Doing this allows the government to stake its claim in defining 'truth' and 'reconciliation' for the process, thus simplifying and reducing an intricate task, raising issues such as whether marginalized narratives (especially ones that go contra to dominant narratives) are given the opportunity to become part of the newly understood meaning of 'truth' and if the government's version of 'reconciliation' between groups has been applied as a one-size fits all. In this sense, truth and reconciliation processes stemming from the grassroots are probably the best approach. Both the Maine Wabanaki and Greensboro TRCs have demonstrated that respecting the historical and cultural nuances of specific communities is a key indicator of engaging in a mutually respected long-term reconciliation and a more collectively understood truth. We recommend that the more a truth and reconciliation commission is tailored for the very society it seeks to examine, the more likely that people will engage with such a process.

What then is the solution? The diversity that exists across the United States, both within and between communities, means that a process of reconciliation should be different depending upon the community involved. For this reason, a nationwide process would not be suitable, but a nationwide solution might be. A single reconciliation process that encompasses an entire country, especially one so large as the United States, may be placing too much faith in the top-down TRC model. Instead, it would be better to follow the examples of Greensboro and Maine, and allow multiple reconciliation processes to occur, which are tailored by the local people. For example, a national fund for regional grassroots truth, reconciliation, and healing activities could be instituted that would support initiatives at a local level between the states and civil society groups. In other words, the TRC models seen in Greensboro and Maine could be tailored and replicated across the country, instead of investing too much in a single process. Separately there could be a Commission of Inquiry and Reform tasked with identifying and addressing the impact of institutionalized racism at the state and federal levels—within enough time and with enough funding to be comprehensive. As so many TRCs have seen their recommendations and official reports collect dust on government bookshelves, such a commission could be the 'teeth' for the recommendations of the reconciliation processes and be given the power to effect structural changes. However, this is a very preliminary recommendation and requires more elucidation.

Third, it should be recognized that the role of children and youth are vital—whether in ensuring that education systems provide accurate historical narratives that will address the historic reality of what took place, or in supporting youth leadership initiatives that will train young people to continue systemic change in the future. In all of this, however, it must be remembered that even a grassroots TRC will need government's commitment to supporting the process, while also recognizing that, in doing so, institutional reform will be required. There is no doubt that the United States needs to begin a conversation around long-term reconciliation, and it requires both the systems and structures of government, and an aware and committed population, to facilitate it. But for a conversation to happen, someone needs to speak first.

The authors would like to sincerely thank Madeleine Lynn, Richard McLaverty, Sizwe Mpofu-Walsh, and Belinda O'Donnell for their help in producing this article.

NOTES

1 These were the racial categorizations used by the government under the apartheid regime, and were also used in the TRC process, for example in the Final Report. They remain in common usage in South Africa with many South Africans self-identifying as "colored."

2 Mamdani, M. (2002). Amnesty or Impunity: A Preliminary Critique of the Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa.

3 Métis children were also sent to Indian Residential Schools, but despite the fact that the Commission "hopes to guide and inspire First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples and Canadians in a process of truth and healing" the experiences of children in schools set up for Métis children have been excluded from the process.