It is not hyperbole to call The Act of Killing an epochal film. Directed by Joshua Oppenheimer, an American based in Denmark, the documentary brings viewers into the minds of mass murderers, illuminates a horrific piece of recent history that few know anything about, and could end up ushering in a new era in Indonesian politics and identity. There has probably never been a film that bears even the slightest resemblance to The Act of Killing and it is highly improbable we will ever see anything like it again.

Background

The Indonesian anti-communist purge of 1965-1966 is perhaps the least-studied and talked-about political genocide of the 20th century. The killings began after a failed left-wing coup in 1965, when members of the so-called 30 September Movement assassinated six Indonesian army generals and announced that they had taken President Sukarno "under their protection." The army quickly suppressed the coup and launched a killing spree of alleged communists, whom they blamed for the coup. Indonesia did indeed have a very large communist party, the PKI, but hundreds of thousands of others, including critics of the military and members of the ethnic Chinese minority, were also killed. (It is also not certain that the communists were responsible.) The army outsourced the work to local gangs and militias, including the massive and still-active Pancasila Youth paramilitary organization, and within a year, at least 500,000 people (with some estimates placing the number up to 3 million) had been murdered and more than 1 million more were imprisoned. The aborted coup also led to the overthrow of the left-leaning President Sukarno, the nation's first president and a leader of the anti-Dutch independence movement in the 1920's and 1930's, who was replaced by military leader General Suharto.

By 1967, Suharto and his right-wing New Order administration were officially ruling Indonesia. Although Suharto resigned in 1998 and died a decade later, this same regime—the one that ordered the killings now almost 50 years ago—remains in control of Indonesia, the fourth most populous nation on the planet. Moreover, international institutions, like the International Criminal Court (ICC), have ignored these cases and influential foreign nations, like the United States, have, at best, also ignored the killings or, at worst, been complicit and supportive of the right-wing government. Therefore, the now-elderly executioners are treated like celebrities in the country. In one surreal scene, an executioner describes his favored method of killing on what looks to be the Indonesian version of Live! with Kelly and Michael, to cheers and laughs from the audience. This was the atmosphere that Oppenheimer stepped into in the mid-2000s when he started making The Act of Killing. As he said on The Daily Show, and to other media outlets, it was like going to Germany 40 years after World War II and seeing the Nazis still in charge.

Synopsis

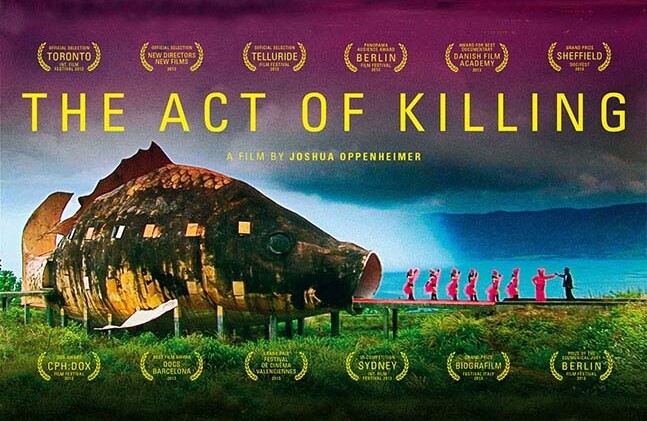

For almost any audience other than a certain segment of the Indonesian population that is clearly enamored with these killers, this history, along with the murderers' current celebrity status, is so appalling that it's almost absurd. So, in making this documentary, Oppenheimer stretched the absurdity as far as it could go. To tell the stories of the death squads, the director had the executioners and their younger sidekicks reenact some of their murders in whatever way they wanted. As the gangsters are big fans of American movies (they were actually called "movie theater gangsters" in the 1960s and ran a business scalping tickets to American films), the stories were told using Western, mafia, and horror movie motifs—each set more ridiculous than the next. It all culminates in a Broadway-inspired rendition of "Born Free," complete with a picturesque waterfall, a giant fish sculpture, dancing girls in pink dresses, and the ghost of a murdered communist giving an executioner, Anwar Congo, a gold medal as a token of appreciation for sending him to heaven.

The key to this documentary is the aforementioned Congo, a 70-something former executioner responsible for up to 1,000 murders. With colorful clothes and a quick smile, Congo, a leader of Pencasila, clearly loves to be on camera and the center of attention. He comes off almost like a hip grandfather—he is so likable and charismatic that you either don't want to believe that he committed these gruesome acts or you want to believe that there was a deeper reason behind his murderous past. Instead, Congo's biggest criticism of the communists is that they boycotted American movies, which made it harder for him and his gang to scalp tickets.

We first meet him (Oppenheimer told Democracy Now! that it was the first time he met Congo, as well) on a rooftop, where many of his killings took place. It's above what used to be a newspaper office in Medan, the largest city on the Indonesian island of Sumatra. Congo matter-of-factly explains that he and his cohorts switched from beatings to strangulation-by-wire because the latter method resulted in much less blood loss. He reenacts his preferred execution style on a friend and then dances the cha-cha-cha. It is an absolutely chilling scene, but even in the levity and his apparent joy surrounding this horrific act, you can see a tortured side to Congo. He admits that he dances and uses drugs and alcohol to make him forget all the horrible things he has done.

Congo's psyche is a stark contrast to that of Adi Zulkadry, his killing partner from the 1960s. Zulkadry flies in to Medan from Jakarta halfway through the filming and provides a steely counterpoint to Congo's antics. Stone-faced throughout the ridiculous reenactments, Zulkadry expresses no emotion toward his victims. He maintains that he feels no guilt, basically because he was allowed to get away with his murders. In one memorable scene, he casually describes killing his girlfriend's father just because he was Chinese. He brushes off the notion of war crimes saying, "War crimes are defined by the winners. I'm a winner. So I can make my own definition."

This contrast becomes even more apparent as the film goes on. It's hard to tell whether Congo becomes more comfortable being filmed or if going through the reenactments actually changes him. But the former executioner is certainly (or at least seemingly) a changed man by the end of the film. After describing a recurring nightmare centered around a man he beheaded and participating in two reenactments in the role of the victim, something switches in Congo's mind. While at home watching a scene in which he pretends to be strangled, his eyes tear up and he tells Oppenheimer, who is behind the camera, that he feels that his horrible deeds are coming back to him. "I did this to so many people," he says. Yet he still doesn't quite understand what he did. He asks Oppenheimer if his victims felt the same way that he did when he played the role of the victim, and the director explains to him, almost as though to a child, that they felt immeasurably worse because they knew they were going to die. In the final scene on the same Medan rooftop where he killed in the 1960s and danced just a few years earlier, Congo is a broken man. No longer laughing and strutting, all he can do is retch and dry-heave as he thinks about the thousands of lives he altered and destroyed.

Reaction This film is mind-blowing, thought-provoking, well-made, and one-of-a-kind. But you probably won't find many critics saying they "liked" it or too many viewers who want to see it again. During Oppenheimer's interview on The Daily Show, John Oliver, Jon Stewart's summer replacement host, perhaps summed it up best. He said, "It took me two hours to watch it, about three days to get over." Tellingly, the British comedian doesn't even try to tell a single joke during the 15-minute extended interview.

This documentary is simply impossible to forget and, from a human rights perspective, could be one of the most important films ever made. It belongs in the same category as Schindler's List in the way it illuminates and even humanizes a terrible moment in history. A main difference, though, is that the Holocaust is taught in schools, cited by politicians and policymakers, and comes up in everyday conversation, at least in the West. Without The Act of Killing, the million or so people who were murdered in Indonesia in the mid-60s might have been forgotten.

The Ethics of The Act of Killing Several books could be written about the ethical questions on display in the documentary, but they basically break down into three categories: ethics relating to 1) the killers who appeared in the film; 2) the role the film has played or will play in Indonesian society; and 3) the role that murder plays (or doesn't play) in films and our everyday lives.

As for the first issue, the obvious question is, should admitted mass murderers like Congo and Zulkadry be given a forum like this? For Zulkadry, the film appeared to have no impact on him. He was the same grim, emotionless man throughout the proceedings. But Congo was clearly affected by the filmmaking process. Still, it must be very difficult for his victim's children and grandchildren to see him become a movie star based on the horrible acts he committed, while 90-year-old Nazis are still being hunted down and put on trial for similar crimes. The counterpoint is the argument that it is always better to "know your enemy." It is educational to know that mass murderers don't have to be hollow, robotic, Terminator types. They can act and look just like your friendly neighbor or grandfather.

In regards to the second question, the impact of this film on Indonesian society was clearly on Zulkadry's mind during the filming. After one reenactment (in which the victim was played by a man whose stepfather was most likely murdered by a death squad), Zulkadry says that this film will probably change the entire narrative of this period of history. For years, he says, Indonesians have been taught that the communists were the cruel ones. Acting out these murders will show that the right-wing executioners were actually the cruelest.

The question is: Almost 50 years on, is Indonesia finally ready to come to terms with what happened? According to a 1997 Carnegie Council article, The Sensitive Question of Transitional Justice in Indonesia," at that time polls showed that apparently,

[M]ost average citizens, many of whom lost relatives to these vicious mass murders, view retribution for them as an obstruction to reconciliation and justice in Indonesia. In fact some intellectuals believe that the retroactive application of justice must not be allowed to go back as far as the massacres of 1965–66. Why? Many argue that all groups were involved in the fighting and violence of the 1960s; whereas the more recent massacres in Timor and Jakarta were a case of government soldiers attacking citizens.But now the time may be ripe. The film has been shown in limited screenings in Indonesia because of its restrictive censoring laws, yet Oppenheimer says it has already "radically transformed the way Indonesia talks about its past." Whether that will lead to police investigations or ICC indictments remains to be seen. But at the very least the world knows immeasurably more about this horrific period and Indonesians can start to come to grips with the fact that their current society was built on one of the most brutal mass murders of the 20th century.

Beyond questions specific to Indonesia, however, this film brings the viewer up-close with actual killers and forces us to see them as human beings, not as monsters that exist only on TV or film or who are locked away for life. Oppenheimer said in several interviews that, aside from some other primates, humans are the only animals that routinely kill their own kind. This point is certainly debatable from a biological perspective—male lions and hippos, for example, often kill younger males because they regard them as a threat. But murder is, at the same time, one of the most common actions that humans act out in make-believe (and not just actors; children commonly pretend to shoot people with their thumbs and forefingers from a very young age), as well as one of the most taboo of all acts. We've all seen innumerable beatings, shootings, stabbings, etc. on movie and TV screens, but how many of us have ever knocked someone unconscious or stabbed or shot someone? How many of us have actually seen a murder being committed? Our society is infused with violence, but those who actually commit violent acts are still seen as outside of society. The Act of Killing brings us into these people's neighborhoods, homes, and minds. It forces us all to understand that when the act of murder is taken lightly, it is immeasurably easier for things like the Holocaust, the Indonesian killings of 1965-66, the Rwanda genocide, chemical attacks in Syria, or even the Sandy Hook massacre to take place.

Ethical Issues and Discussion Questions

1. Should mass murderers like Congo and Zulkadry be given a forum to tell their stories?

2. Does this film glorify violence in any way? Can TV, film, or other art influence people to commit violent acts?

3. Should Congo and Zulkadry be prosecuted for their crimes? Should Nazis still be prosecuted for their crimes? Should there be any statute of limitation on war crimes?

4. How should Indonesia deal with this episode in its history? How should children be taught about the killings?

5. Can a film really affect the human rights dialogue in Indonesia or any other country?

6. In The Act of Killing, should Oppenheimer have paid more attention to the victims?

7. Why has the Indonesian anti-communist purge been forgotten by the world at large?:

Selected Carnegie Council Resources

What Does It Mean to Prevent Genocide? Tibi Galis, Aushwitz Institute for Peace and Reconcilliation; Kyle C. Matthews, The Will to Intervene It's essential to understand that genocide is a process, not an event, says Tibi Galis from the Auschwitz Institute for Peace and Reconciliation. It doesn't just happen out of the blue. So there are chances to step in and change the course of this process.(Carnegie New Leaders, June 2012)

EIA Interview: Antonio Franceschet on the International Criminal Court Antonio Franceschet, University of Calgary What is the role of the International Criminal Court today? What are its strengths and limitations? In this informative interview, Professor Antonio Franceschet discusses the evolution of the ICC; its basic structure and function; and its current and future challenges.(EIA Interview, April 2012)

Recent Advances in the Prevention of Mass Violence David A. Hamburg, Carnegie Corporation of New York How can we prevent mass violence? Drawing on insights from leaders in the field, David Hamburg identifies the clear warnings that always appear long before genocide erupts and the critical points of entry for early help to countries with troubled intergroup relations. (U.S. Global Engagement, March 2010)

Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, Harvard University Rwanda, Bosnia, Cambodia, Darfur, Congo, and more—since World War II, genocide has caused more deaths than all wars put together. Goldhagen analyzes how and why genocides start and proposes steps the international community can take to stop them.(Public Affairs, October 2009)

Pious Words, Puny Deeds: The "International Community" and Mass Atrocities Rajan Menon, University of Calgary Most of the large-scale violence in the world will continue to occur within societies rather than between or among states. Yet the international community still has not developed the ethical-legal consensus or the institutions required to manage this terrible problem. (EIA article, Fall 2009)

"Unspeakable Truths: Confronting State Terror and Atrocity", Priscilla B. Hayner; "Transitional Justice", Ruti G. Teitel David A. Crocker, Institute for Philosophy and Public Policy, University of Maryland Both authors describe the variety of tools—national and international trials, investigatory bodies, memorials, reparations, and constitutional changes—that societies and international bodies have employed to address human rights violations.(EIA book review, Fall 2001)

The Sensitive Question of Transitional Justice in Indonesia Andreas Harsono, Indonesian journalist and human rights researcher Andreas Harsono examines whether Indonesian President Suharto would take the risk of stepping down for democracy and allow himself to be prosecuted for human rights violations of the past. (Human Rights Dialogue Article, Spring 1997)

Transitional Justice in in East Asia and its Impact on Human Rights The focus of this volume is on how transitional societies—those experiencing a transition from a repressive regime to a more democratic society governed by the rule of law—in North and Southeast Asia have responded to, or might respond to, allegations of gross human rights violations by the preceding or extant regimes.(Human Rights Dialogue, Series 1, no. 8, Spring 1997)

Works Cited

"'The Act of Killing': New Film Shows U.S.-Backed Indonesian Death Squad Leaders Re-enacting Massacres", Democracy Now!, July 19, 2013

"Joshua Oppenheimer Extended Interview", The Daily Show with Jon Stewart (guest host John Oliver), August 13, 2013

"Indonesia's Happy Killers", The New York Review of Books, Francine Prose, July 18, 2013

"Indonesian killings of 1965-66", Wikipedia, Last modified on August 4, 2015