It snowed last night briefly in Kabul, but today the sun is out, the snow has melted, and the streets are crowded. There is no electricity this morning, but the generators are running and the heater is working in my hotel room. Outside the birds are singing.

At 6,500 feet, Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, is in a valley surrounded by mountains. The name means "straw bridge" in Dari, a Persian dialect that is the main language in the north, and the city remains a bridge between the Tajik, Turcoman, and Uzbek north, and the Pashtun south. (The Pashtuns speak Pashto, but most are bilingual in Pashto and Dari.)

The Pashtuns are the founders of Afghanistan, carved out of India and Persia in the 18th century by Ahmed Shah Durrani, a Pashtun from Kandahar in the south. Hamid Karzai is a Pashtun. The Taliban are Pashtuns. I hesitate to say how many Pashtuns there are, because figures vary widely and there has never been a true census taken here. There are perhaps 12 million Pashtuns in Afghanistan; they are the country's largest ethnic group. But there are 40 million Pashtuns in Pakistan. This is important in understanding the power of the Taliban, and its backers.

In 1893, Sir Mortimer Durand, Foreign Secretary of British India, drew the now famous Durand Line, which became, in theory but not in practice, the border between what was then colonial India and Afghanistan. Today it is the border—but not to Pashtuns—between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

There is not a Pashtun in Afghanistan who feels that the Pashtun nation ends at the Durand Line. For them, rather, the border goes deep into Pakistan, all the way to the Indus River, and south into what is today the Pakistani province of Baluchistan. There are a great many Pashtuns in Baluchistan, where many Western observers—and this includes NATO and U.S. military leaders—believe that Mullah Muhammad Omar, leader of the Taliban, is hiding.

(The region in western Pakistan along the Afghan border is called the Northwest Frontier Province. It is where the world thinks that Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri are hiding. These two men are Arabs and neither, from all that I have ever heard, speaks Dari or Pashto. However, it is not clear to me that they are where everyone thinks they are.)

The British were never able to pacify the Pashtuns. They lived on the western edge of British India and have been there for at least 6,000 years and probably longer, as long as any tribe has lived in any area anywhere in the world. They were too tough, too adept at guerrilla warfare, too capable with a rifle. The archetypal Pashtun male is a warrior and a poet.

When Pakistan was founded in 1947, Afghanistan was the only country to vote against admitting it to the United Nations. No Afghan government, and this includes the present Karzai government, has accepted the Durand Line as the border of Afghanistan. This too is important to note when studying al-Qaeda and the Taliban. It is important because many believe this region is the world headquarters of al-Qaeda.

In 2002, at the request of and paid for by the United States, the Pakistani army, for the first time in its history, moved up along the Durand Line. Today there are over 40,000 U.S. and NATO soldiers over the border in Afghanistan, from largely Christian nations. This is the largest number of foreign soldiers in Afghanistan since the 1980s, when the Soviet Red Army was here, fighting a Muslim Pashtun-led insurgency.

But back to Kabul. It is a Tajik city. The main language here is Dari, not Pashto. When Mullah Mohammed Omar, a Pashtun, was leader of Afghanistan, he only visited Kabul once or twice before retreating back home to Kandahar, his headquarters, in the south, deep in Pashtun territory. When I first came here as a boy, in 1973, it was a small, beautiful city of 225,000, called by some the Paris of Asia. Long camel caravans plodded softly through the streets, and at night, turbaned police with rifles on their backs patrolled slowly on horseback. The night sky was clear and bright and filled with a billion stars. At prayer times, you could hear the muezzin's call to prayer mixed with the sound of the Rolling Stones.

There were 5,000 hippies here then, lying in the sun listening to music and smoking hashish during the day, and going to make-shift discothèques at night. Although they did not know it, they angered the Afghans, who had to work hard all day to get enough to eat. According to the late Louis Dupree, the most prominent American Afghan anthropologist of the 20th Century, (whose widow Nancy Dupree shuttles between Kabul and Peshawar, Pakistan, helping to develop a new library), the drug trafficking which has so corrupted Afghanistan and made it the world's center for opium poppy growing began with the hippies, who smuggled hashish back into Europe and North America.

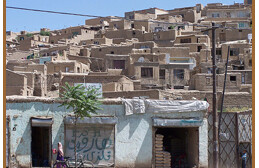

The Kabul of today does not resemble the Kabul of the 1970s. There are three million people here now. Real estate is expensive, because foreigners drive up the prices; the pollution and traffic are so bad that policemen wear surgical masks, and some carry rifles, as they attempt, but do not succeed, to direct traffic. In the ten days I have been here, walking through the city, I have seen only two other foreigners on the streets. The rest ride around in comfortable sports utility vehicles, many of them (though certainly not all) afraid of the Afghans and of this once proud and beautiful city.

But you can't blame them. They are afraid, as are most Kabulis, of suicide bombers. On Sunday, in Paktika Province, down along the Afghan-Pakistani border, there was another suicide bomb, the 98th this year. The last one in Kabul was in September, when 15 people died. A suicide bomber killed a Western female aid worker on Chicken Street. This famous tourist haunt is now empty of foreigners. I remember the delicious apple turnovers you could buy on Chicken Street in the 1970s, when Kabul was like a small town, and it was romantic, when a young traveler could daydream about taking the famed "Golden Road to Samarkand," and when traveling through the Khyber Pass to Pakistan was like going on a Sunday drive.

I can still picture the beautiful nomad girl making bread over a fire outside her tent on the outskirts of Kabul. I was sitting with her family drinking green tea. I remember how softly her parents talked to one another and how elegant her mother seemed, in her long colorful dress and silver jewelry, as she walked barefoot around her tent. The girl smiled shyly, looking down, as girls would anywhere in the world. That was when people read James Michener's Caravans about Afghanistan, and not books on al-Qaeda, bin Laden and the Taliban.

In 2002, Kabul, while crowded, and filled with Northern Alliance soldiers, was a happier place, a city beginning to fill with traffic, but also with hope. Women were taking off what journalists, unfamiliar with Afghan culture, incorrectly called the burka, and men were shaving their beards. The West, particularly the Americans, was boasting about how quickly and easily it had defeated the Taliban.

Today the Taliban, in various forms, are coming back, frightening the West and the people in Kabul. The line outside the Iranian Embassy, where people are applying for visas grows every day: "rats fleeing a sinking ship," said a British journalist friend who married a Kabuli, and has lived here for 20 years. We were having lunch with an assistant to Ahmed Shah Massoud, the famous commander killed, by all accounts, by al-Qaeda two days before 9/11. "Our hope is gone," he said. "The Taliban are getting closer. We are watching and waiting for when we will again fight in Kabul."

There is a new Coca Cola bottling plant here, and seven-story high-rises, one with an elevator and a rooftop restaurant. There are French, Italian, and German restaurants. Most of the women in the streets only wear a chador, or scarf, on their heads; young women walk alone or with boys their age, as they would in New York or Paris; young men jog in Shar-e-Now Park early in the mornings; middle class women walk through a new shopping mall, with an escalator, looking at clothes or buying perfume; there are women in Parliament; men and women parliamentarians dine together in restaurants; there is energy and there is construction.

But then I watch the military convoys come through the streets, and talk to people, and wonder about the future. The writ of the Karzai government is said to reach only to the end of Kabul, and even then it is not certain. Everyone talks of corruption at all levels of society, although President Karzai himself is not implicated.

When I was young, one of the reasons why I fell in love with Afghanistan—besides its beauty, the warmth of its people, and the romance of it all—was that it was the only country I visited where children, no matter how poor—and Afghanistan was and is one of the poorest countries on earth—did not beg. They did not cry out "baksheesh, baksheesh," like little children did in other poor countries in the Middle East, North Africa and Asia. There was a dignity in them, born of a harsh, but proud life, and rich heritage, taught to them by their parents.

Today there are 50,000-60,000 children, it is said, most of them orphans, working the streets of Kabul. Years of war have taken their toll. A little girl yesterday grabbed my coat and hung on, putting her hand to her mouth, begging for food. Little girls attempt to wash your windows. It angers you and breaks your heart.

Cell phones are ubiquitous in Kabul and you can watch the BBC, CNN, Al-Jazeera in Arabic and English, and Afghan television with its own version of MTV. But the Taliban have promised to fight through the winter. When I lived with their older brothers, the Mujahideen, exactly 25 years ago as a newspaper reporter, they hunkered down in the winter, except in the far south, where it was warmer. The U.S. Ambassador, Ronald Neumann, whose father was ambassador here, said a few weeks ago that the war will be just as bad next year. To me this means it will be worse. British, Canadian and Dutch soldiers are doing most of the fighting in the south, much to the chagrin of their populations back home, who are not happy that they are here.

I went for a run through the streets just after dawn the other day and an Italian convoy passed by, its soldiers in body armor, armed to the teeth. A soldier waved and I waved back. Everyone stays away from convoys. The suicide attackers target them. The West does not seem to realize that the Christian world cannot impose itself blindly upon Afghanistan. Americans, a man said to me last night, need to realize that not everyone wants to be an American. High rises and modern restaurants do not mean anything to people who are willing to live in the mountains in the winter and to die for what they believe is right.