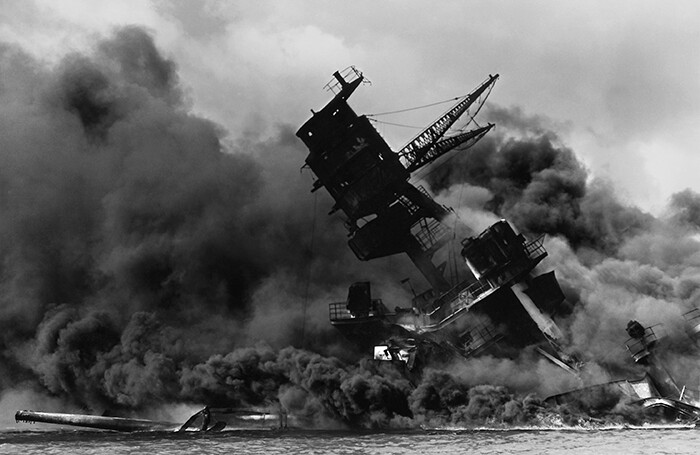

This statement was presented at the Annual Meeting of the Church Peace Union (now Carnegie Council) on January 15, 1942. It was also published in the World Alliance Newsletter, February 1942. Its author, the Rev. Henry A. Atkinson, was general secretary of the Church Peace Union from 1918-1955. The war was a terrible blow to all those in the peace movement, especially as many vividly remembered WWI, "the war to end all wars." Throughout the 1920s and '30s, the CPU and the World Alliance for Churches campaigned to reduce the naval arms race, establish the League of Nations, and prevent another world war. As reported in this statement, a friend asked Atkinson, "At a time like this, with all your work of twenty-five years gone, how can you have the courage to go ahead?" But the indomitable Atkinson was already planning for after the war.

The Church Peace Union was founded and began its activities almost at the same time that war broke out in Europe in 1914. The world was bewildered and the churches were caught utterly unprepared for such a catastrophe. Most people, and among them the best informed, believed that the conflict could not last more than a few months, and those who saw a long, hard war were dubbed alarmists and war-mongers. The churches were inevitably drawn into the conflict; but to say that they became martial-minded, or that they spent most of their energies in blessing the war and paying no attention to what was to follow, is incorrect. Many unwise and some beastly things were said from pulpits as well as from forums all over the country, but for the most part the churches continued their normal work under exceedingly difficult conditions. The fact that such a war could occur in this century was in itself almost a complete refutation of all those principles which the churches had espoused and preached.It is interesting to find in most of the literature which was published by the churches at that time, that where there was one reference to the war, as such, there were a hundred references to what would follow after the war. One of these publications, of which nearly a million copies were circulated, is entitled "Keep the Churches Back of the Soldiers." On the cover is the picture of a church with marching soldiers in the foreground. The material in the pamphlet clearly indicates the responsibility of the churches under war conditions. Two million men were in active service and eight million more were under draft. These ten million men came from the homes, churches and schools of America. Certainly the churches could do nothing less than stand back of those who were offering their lives in defense of our liberties and for the future of our country. Another pamphlet is a study course on the subject, "the world we want after the war." The National Committee on the Moral Aims of the War, which has been lampooned by those who have not taken the trouble to read the program of the committee or the record of its activities, was in fact an organization which primarily promoted the new effort to create a "League of Nations." The group which first discussed the proposal to establish the League of Nations, after the war, held its initial meeting at the Century Club under the chairmanship of the Hon. Theodore Marburg. Among those present were Hamilton Hold and George A. Plimpton, both Trustees of the Church Peace Union. A series of conferences followed with Mr. Marburg acting as host and chairman. At a subsequent meeting held in the offices of the Church Peace Union, an organization and took offices at 70, Fifth Avenue, new York City. This organization took the name, League to Enforce Peace. Its purpose then has now been fairly restated by Mr. Churchill in a recent speech. He said:

It has been proved that pestilences may break out in the old world which carry their destructive ravages into the new world, from which, once they are afoot, the new world cannot escape. Duty and prudence alike command that the germ centers of hatred and revenge should be constantly and vigilantly served and treated in good time, and that an adequate organization should be set up to make sure that the pestilence can be controlled at its earliest beginning before it spreads and rages throughout the entire earth.It was for the establishment of the League of Nations that this voluntary group worked, and in this it was successful. The churches became strong proponents of the movement.

The Churches and the War

Again the churches are faced with the choice we had to make in 1917. This time we have a better understanding of what war means and the problems entailed.

The churches of all creeds and faiths have a real stake in the outcome of the war. Many proposals for permanent peace are being considered, such as the outlines issued by the Commission to Study the Organization of Peace, by the International Labor Office, and by the churches of Great Britain in a recent report. Any of these major proposals is adequate but to make effective the proposals a degree of patience and understanding is needed, a willingness to compromise, a clear evaluation of the greater good over the immediate profit, and a fund of good will—all of which are essentials of a religious approach to the subject. And nothing can be achieved without this background. This is eminently true of the perplexing economic and commercial problems.

There is no need to labor these points. A just consideration of what our attitude must be toward the war and the peace which is to follow is important. this can only be secured through weighing the history of the immediate past.

Churchmen, Christians and Jews, have responsibilities as citizens of the United States. They are faced with the alternative of supporting the government and helping to win this war, or of refusing and so helping to bring about our defeat.

The Trustees of the Church Peace Union join with the overwhelming opinion of their countrymen in support of our government in winning this war. The war must be won for there can be no peace until aggression is stopped and it will not be stopped except on the battlefield and by the might of armed forces. Therefore we must support the war.

Few Christians will accept the statement that we must be Christian, even if that means enslavement by the ruthless forces which have no enslaved or threaten to enslave a large part of the world. We are not forced to accept slavery as Christians, or freedom as pagans. There is no truth in the Nietzchean formula which places these two extremes as the only alternatives before us.

To view our responsibilities, members of all faiths must think of themselves as citizens and as members of the community. The community—every community—is responsible for helping in this crisis which faces us all. There are three major institutions in every community, the home, the school and the church. All of these agencies must be enlisted in every community if the war is to be won. The home does its part. It is from the homes that the boys are going out to take their places in the battle-lines, in the skies, on the oceans. The school is educating and training in citizenship. The church also has a particular relationship, for after all the community is dependent for its future on the establishment and maintenance of high moral and religious principles. The home, the school, the church—each is involved in the winning of this war and in the winning of the peace. If any one fails the community will be weakened and the danger of defeat will be increased. If either fails to contribute its full strength in the effort the conflict will be longer and more difficult. Each must make its contribution in its own sphere and at the level where it can be most effective.

We are particularly committed to work with and through the churches. This does not mean that we will exhort the churches to transform themselves in this time of war into agencies of the armed forces. It does not mean that the ministers are to don uniforms and make their pulpits rostrums for the discussion of the conduct of the war, or that the church is to be brought into the conflict as an institution which takes orders from the military forces. But what is true of the church is also true of the home. The homes will be maintained, not as adjuncts of the military, but as integral parts of the community serving the nation and making it strong through the strength of normal, wholesome human lives. Thus, each will be a unit in the nation contributing all its power to the protection of the nation, to the winning of the war, and to the establishment of peace. The home which turns itself into an adjunct of the army ceases to be a home in the real sense of the word. The same thing applies to the schools. The schools will do their part. Of course, the schools, just as the home, will change some of their customary routine. The home will have to modify and adjust its habits of diet, pleasures and recreations, and the schools will have to change their curricula to conform to the war situation. However they will not abandon the primary service which they—and only they—can render. If the home fails there is no basis left for the inculcation of morals at the time when habits of thought and patterns of action are being formed by the future citizens of our land. If the school fails, half-educated people will be poor material with which to build and operate a world after the war is won. By like reasoning, the churches will have to share the hard days ahead and make many adjustments, but they must not abandon their purpose and turn to other tasks for which they are ill fitted for if they do they will be giving up the opportunity of serving in the best possible manner and in a way that will be needed in an ever larger degree as the war efforts are intensified.

The churches will naturally think, first of all, in terms of their local communities. The war-time program of each church should be based on the maintenance of morale, and morale means stamina, courage, and faith to keep one's balance and avoid panic in times of stress and danger. Other immediate tasks of the church will be:

- a. to render service to our own armed forces;

- b. to continue all the regular educational and inspirational services of the church;

- c. to help promote a study of those things for which we are fighting; d. to cooperate with other agencies in the community in studying and promoting the organization of peace after the war.

Here is a program which should command the best efforts of all. There will be constant demands upon us to meet with civilian groups working in behalf of the war effort, with groups studying plans for peace, with groups studying various phases of post-war reconstruction, with groups raising money for hospitals, for the Red Cross, for particular ventures connected with the war. All of these will be a part of the community activities, and the success of the church will be dependent on the amount of assistance it can give to these various enterprises, in addition to carrying on its regular services and programs. Total war means that every community and every individual are involved, and total war will demand the utmost in sacrifice. It gives no place for any individual or group to escape from its full responsibilities.

The Churches and the Peace

The greatest task that the church must face is in the period after the war is won. I have no doubt that the great majority of the churches will do their full share in the war effort, and they will do it more intelligently and with less fanfare than in the last war. The churches must feel that they share in the responsibility for the conditions which have brought upon the world this second great tragedy. Let it be hoped that the churches will not "grow weary in well doing" when the war is over. It is easy enough now to study plans for the promotion of peace when the war is ended. To many such a study will provide a way of escape from present responsibilities. Conferences can be held and the forms of world organizations discussed; but when the war is over then the question is going to arise, "what attitude will America toward the rest of the world?" It will not be quite so easy then to maintain the close comradeship which now exists among America and her allies. The old jealousies will come back. The old interests and suspicions will assert themselves. We will enter a period when the question of our relation to the peace machinery of the world will not be merely a theoretical issue, but will be real politics. Before 1918, as I said before, the churches were unanimously in favor of some kind of a league of nations. When the league was founded it was hailed as a new order on earth, and some of the sermons preached at that time identified the League—growing out of the Versailles Treaty and its adjustments—with the establishment of the Kingdom of God on Earth. "Now that the Kingdom has come we may expect all the good things that have been promised." Then through party divisions the League became a football in the political arena. The churches and organizations which had staunchly supported the League began to falter in their support. they still professed to believe in "a league but not in the League." But why go through the dreary history of those years?

The same narrow isolationist forces in the United States, now driven underground, will come forth just as quickly as they dare, and they will put up the same fight. We know who these people are, and we know the selfishness and short-sightedness which motivate them. Are the churches going to be strong enough this time to stand and fight for the establishment of a world order which will prevent war, or will the churches be too busy with other matters and too engrossed in perfection to dare to soil their hands with a fight in the political arena? This is the essence of the issue we shall face and this is the issue we must be prepared to meet

Let me say that this does not mean that the churches are to become simply adjuncts of party politics and their issues, but they must emphasize the moral implications of winning the peace and then stand for them above the political exigencies and the political maneuvering the the days that are ahead.

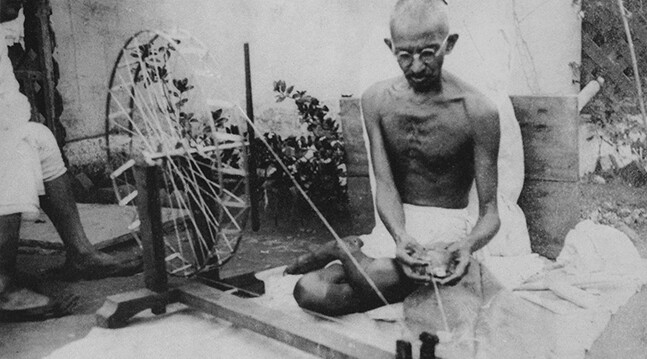

We need not doubt the future. A friend of mine said the other day: "At a time like this, with all your work of twenty-five years gone, how can you have the courage to go ahead?" I said to him: "The men and women which whom I am working are the men and women who believe that no cause is lost as long as there is one person left who believes in it, and is willing to give his time, his best intelligence and his life for that cause." It is only two or three years since the League of Nations was called a "dead issue." "The League is finished." "It will never come up again." But if you have followed the editorials which are now appearing in the leading papers of the country, you know what they are saying about the League. All over our land Woodrow Wilson is again being exalted into a place of leadership. The New York World Telegram stated recently:

Winston Churchill's address to the Congress and the anniversary of Woodrow Wilson's birthday were both reminders, if any were needed, that in winning the war we shall lose it unless we also win the peace. Fate will not let us forget that the need is international organization, whether it is called a League of Nations or something else. Woodrow Wilson did not think victory in war would make the world safe for democracy, but he did hope that a wise and just treaty providing conditions of prosperous, peaceful living for vanquished and victors alike, buttressed by an international organizartion to settle future problems peacefully, might achieve liberty and plenty for the world. Because that dream failed, the peace was no peace but only an armed truce.In the New York Times, in a recent editorial on the birthday anniversary of Woodrow Wilson, the following appeared:

In the years between the last World War and our entry into this one, it had become the fashion in many places to scoff at the phrases with which our last war-time President clothed his vision, if not at his ideals themselves. Yet today we are fighting to obtain for ourselves and for the rest of mankind the kind of world which he hoped might be achieved in that other great conflict. Is it not fitting that on this anniversary of Woodrow Wilson's birth we should look into our hearts and see whether his failure sprang, not from the idealism of his planning, but from our own inability to comprehend it or to accept those responsibilities?The League as an institution still exists: thirty-six nations sent delegates to New York last autumn to attend a meeting of the International Labor Organization; the League building stands; the ideal is growing, and throughout the coutnry there is a feeling that Wilson built even better than he knew. As the New York Times stated in an editorial on the occasion of the twenty-second anniversary of the founding of the League of Nations: "Woodrow Wilson's body, like John Brown's, lies moldering in the grave, but his soul goes marching on."

All this is reminiscent of the account given of the apostles of Jesus who were arrested in the city of Jerusalem for preaching the new gospel. The authorities made up their minds that this thing had to be stopped. The politicians got busy and the "men who were turning the world upside down" were thrown into prison. Then they escaped. One of the village gossips came and told the authorities, apparently either with some degree of satisfaction or perhaps with some cynicism: "Behold the men whom ye put in prison are now standing in the temple and teaching the people."

This is no time for us to quit. This is the time for us to go deliberately and firmly ahead in the plans we are trying to carry out. We have the program. We have the courage. We have the faith in the living God. We have the sanctions of the religions we profress. Dr. George W. Gray in his story of the Rockefeller Foundation's work, particularly relating to the history of the International Education Board, says the following:

Once more war demonstrates itself as the negation of science, whose Magna Charta [sic] is freedom of thought, freedom of inquiry, freedom of communication. And democracy, that luminous ideal. ...is now in eclipse in large areas of the world. But eclipse is not obliteration. The sun is blackly obscured, but it will shine again. Hope feeds on the intergrity of law, both cosmic and moraal; on confidence in the natural order gy which light follows darkness. And so, despite the destructive forces which came into the open in September of 1939 with the invasion of Poland, the results ... are still creditable to the human spirit. They still carry a promise for the future. No star is ever lost, and after the present transition through blood and night is over, surely these beginnings laid in friendliness and collaboration in the post-war 1920's will carry on to serve in another postwar period of reconstruction and reconciliation.**Quoted from Education on an International Scale—Courtesy, Harcourt, Brace and Company.