WORLDVIEW Magazine ran from 1958-85 and featured articles by political philosophers, scholars, churchmen, statesmen, and writers from across the political spectrum. Find the entire archive online here.

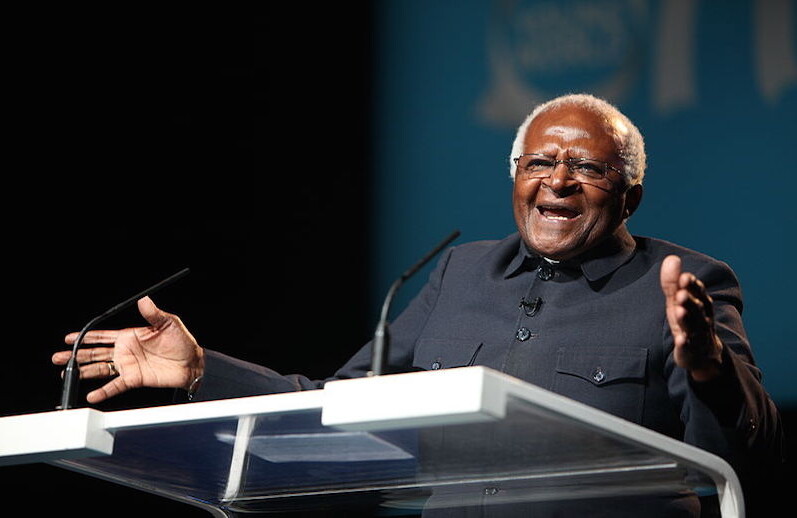

Rafael Suarez, Jr., is a Los Angeles-based correspondent for Cable News Network [CNN], which originally broadcast this interview and through whose courtesy it has been made available to Worldview. The interview took place on Wednesday, October 10, at St Alban's Episcopal Church in Westwood, Los Angeles. On the following Tuesday, Bishop Tutu was notified of the decision of the Oslo committee to award him the Nobel Prize for Peace.RAFAEL SUAREZ: The subject most in the news lately concerning South Africa is the drafting of a new constitution. As many Americans know, the constitution includes the so-called coloured and Asian populations in the new political process, but not the blacks. What is your position on the new constitution? BISHOP TUTU: We have no doubt at all that it is something to be rejected out of hand because it is totally undemocratic, excluding as it does 70 per cent of the population. The three chambers provided for by the new constitution merely entrench ethnicity. We have the 4-2-1 ratio: four whites, two coloured, one Indian in the committees, which means there is no hope whatsoever that the coloureds and Indians could ever outvote the whites. And so you are entrenching white minority rule. It is a smart effort at hoodwinking the international community.

Some of the leaders of the new assembly who are coloured and Asian say "the door is opening a crack and we would be foolish not to put our foot inside." At the same time, many black leaders would refer to a man like Alan Hendrickse, coloured leader in the new assembly, as a sellout. I don't know what word I would use for him; all I would say is that in the past he has been involved in the Coloured Representative Council, that his party—the Labour party—has said it wants to undermine apartheid, change the system from within. And they failed dismally. If they failed when the stakes were so low, how, in the name of everything that is good, do they expect to succeed in bucking the system now that the stakes are so high? I cannot really understand this. All that is happening is that the government is coopting them and making of them collaborators in the system of oppressing blacks, and thereby postponing the day of liberation. And we have said to them: "You know, in a situation of injustice there is no in-between position. You are either an oppressor or the oppressed." And they know too that they will not be able to change the system even with Indians in the parliament. There is one whole province in the Republic of South Africa where Indians are not even allowed to stay, the Orange Free State. It's weird.

Many friends of black South Africa in the West look at this change and see some reason for hope. Consequently, they are willing to release pressure on South Africa a little bit. You, however, reject it outright. Does this cause you more difficulty in stating your case against the South African Government? Not at all. Because if the government was concerned with fundamental change toward what we would call real political power sharing, they would not have produced a fait accompli—a constitutional change in which they virtually said "take it or leave it" to coloureds and Indians. After all, they didn't even have the guts to let the Indians and the coloureds test in a referendum whether or not they wanted the new constitution. Basically, they were trying to play out a public relations exercise, to say to the West: "We are changing." Do you usually ask the perpetrators of an injustice to say whether things are now getting better? Don't you ask the victims? If you ask the people in the squatters camps, those black women whose flimsy shelters are destroyed daily, if you ask them, "Is apartheid getting better?" I am sure they would answer with a resounding, No! If you ask the three-and-a-half-million blacks who have been uprooted from their traditional homes and thrown into places where they do not belong, "Is apartheid changing?" they would say to you, No! If you ask the 200,000 blacks who fell afoul of the pass laws last year, "Are things changing?" they would say: "If they are changing, they are changing for the worse." And if you ask blacks whose children are receiving inferior education—200,000 black children are boycotting the schools—if you ask them, "Are things changing?" they would say: "Well, why do you think we are boycotting?" And so it is that the West wants to believe that things are changing. If things are changing, then Western governments don't have to do anything that may be unpopular with their constituencies.

But at the same time that the new constitution has been put into effect, the regime has freed Herman Toivo ja Toivo [the founder of the Southwest African People's Organization, SWAPO, in detention for nearly twenty years] and has released Beyers Naude [former general secretary of the South African Council of Churches] from his banning order. In addition, Mozambique and Angola have been pacifed in their border relations with South Africa. To an observer in London or Paris or New York, Botha and company are moving forward. Let me ask you, then, why is South Africa in Namibia if the international community, the United Nations, and the International Court of Justice have concluded that South Africa is an illegal occupying power?...You say Beyers Naude was released from his banning order… Why was he banned in the first place? Why, if there was some contravention of the law, have they not taken him to court? They are banning people arbitrarily. Why have they still got eleven people banned? Why is Mrs. Mandela [Winnie Mandela, wife of African National Congress leader Nelson Mandela, now serving a life term on Robben Island] banned? Why is she still in banishment? They have never told anyone. I am quite certain that even if they had the flimsiest evidence, they would love to get her into court. They use this bureaucratic method of dealing with dissidents because they can't stand the use of the ordinary due process.

South Africa maintains that the reason the security system is so stringent and the reason that the writ of habeas corpus has been suspended on occasion is that the country is encircled by enemies and that it cannot look to the outside world for help. It is the last outpost on an increasingly Marxist continent. Is it true that there really is no enemy without, only an enemy within? You can't have it both ways. I mean, they have been doing a song and dance about the fact that they have just signed a nonaggression pact with Mozambique. They cannot now turn around and say there is an enemy in Mozambique threatening them. The two things don't go together. Botswana is not threatening, and would never be a threat to South Africa. Lesotho, as you bow, is held to ransom...South Africa has a stranglehold on Lesotho. It has a stranglehold on Swaziland. It's baloney! They know that, especially with the United States, the minute you say "I'm anti-Communist'' it doesn't matter what your human rights record is. Who in the world could say they are upholding Christian values when they are excluding 70 per cent of the population from any meaningful participation in decision-making? Who in the world could do what they are doing to the Crossroads people [black squatters in "white" territory eventually removed by force in the Cape Province]? I am glad I'm not a Westerner; I am glad I'm not white; I am glad I'm not civilized, if civilized means doing the kind of things that the South African Government is doing to uphold what it calls Western, white, Christian civilization. And I'm not Christian if those are the standards you have to go by.

As a churchman you are often criticized for being involved in trying to define the political choices that have to be made in South Africa. No doubt this is a convenient club for those who want to pick it up, but where do you draw the line if you decide that your ministry is to preach a social gospel? Where do you stop? I don't preach a social gospel; I preach the Gospel, period. The gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ is concerned for the whole person. When people were hungry, Jesus didn't say, "Now is that political, or social?" He said: "I feed you." Because the good news to a hungry person is bread. When you are ill, I heal you. Those are physical, mundane, secular, nonreligious things. And you remember the wonderful parable we have about the last judgment. He said that when we are judged about whether we will go to heaven or to hell, it will be by thoroughly nonreligious criteria. He didn't say that you will be asked: "Did you pray? Did you go to church?" He didn't mean that those were not important things. But you will be judged by whether you fed the hungry, whether you clothed the naked, you visited the sick and those in prison. I have no conflict with this whatsoever, because all of life belongs to God. I can't believe that you can compartmentalize life and say this is political and this is religious, because for us religion must permeate the whole of life. If people wish to say, "God's writ does not run in the political sphere," I want to ask, "Whose does?"

At the same time, those who would criticize you for being a political priest would also take exception to what they would see as a hands-off or soft-glove approach to those who would oppose the regime using violent means, like the African National Congress (ANC). Where does a Christian come down on the use of violence for social change? I think it's really important for me to tell people that the situation in South Africa is violent already. And the primary violence is that perpetrated by the South African Government against us blacks. It is the violence of the forced population removals, it is the violence of inferior education, it is the violence of exclusion from any meaningful political participation, it is the violence of letting children starve in a country which is a net exporter of food. That is what people have to recognize. And to recognize too that our people have been peaceful to a fault...One of the presidents of the ANC is the only African to have won the Nobel Prize. Chief Luthuli won the Nobel Peace Prize in tribute to the commitment of the ANC to peaceful change. What happened when black people protested peacefully in 1960, on the 21st of March, in Sharpeville? Sixty-nine were killed, most of them shot in the back. In 1976 our school children, singing in the street protesting against inferior education…what happened? Over five hundred people were killed as a result of that peaceful demonstration. And now over sixty people have been killed, again at a time when people are trying to protest peacefully. And I would say that the West is the last section of the world that can tell people "Don't be violent." The United States, how did it win its independence, by sitting down and folding its arms? The history of most Western countries is written in blood. No, we are quite firm actually in the South African Council of Churches. We say we are opposed to all forms of violence. The violence of a repressive, unjust, system ... and the violence of those who wish to overthrow it. We also say that we do understand when people say: "We have tried everything, and now, because the South African Government has banned organizations like the ANC, we have no option but to undertake the armed struggle."

So what do concerned people in America do? We have a government that throughout its history has not been malicious toward Africa; it's more a case of benign neglect. What does an American citizen do to make his voice heard on what's going on in South Africa? I must say that we are deeply distressed at the role that America has played in buttressing an intransigent, repressive regime such as that in South Africa. They have got a policy called constructive engagement in which they say they will not publicly admonish South Africa or speak up in favor of human rights when they are violated there. And we think that is very odd. Because when something happens in Poland, and Solidarity is touched by the Polish Government, before you can say Jack Robinson the U.S. Government, without consulting anyone, applies sanctions. What happens when the same thing is done to black trade unionists in South Africa? They tell you—they have the temerity to tell you—"Sanctions don't work."... Just as much as apartheid has given a bad name to free enterprise, so the U.S. Government has given a very bad name to democracy.

Paton on the Prize

(Johannesburg, Johannesburg Domestic Service, in English, Oct. 24) The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to the general secretary of the South African Council of Churches, Bishop Desmond Tutu, has been widely acclaimed at home and abroad, but it emerges very clearly from the tributes published in newspapers that not all the bishop's views are shared by his admirers in South Africa. One of the causes Bishop Tutu most assiduously promotes on his overseas visits is disinvestment, and it is on this question that even his most ardent admirers in South Africa disagree with him. One of the country's most well-known liberal thinkers and critics of the government, Dr. Alan Paton,— questions the bishop's morality on the issue of disinvestment...Dr. Paton says he cannot understand how Bishop Tutu's Christian conscience can allow him to advocate disinvestment. "I do not understand how you could put a man out of work for a high moral principle...It would go against my deepest principles to advocate anything that would put a man, especially a black man, out of a job, therefore I cannot understand your position." Dr. Paton's view coincides with that of all responsible leaders in South Africa—black as well as white—and also with two-thirds of the black workers in the country. It is not only the blacks within South Africa's borders who will be hardest hit by successful economic moves against the country. The economic interdependence of states in southern Africa is such that no one in the subcontinent will escape the effects of disinvestment from the republic. It has been pointed out to Bishop Tutu by his admirers that, as a Nobel Peace Prize winner, he will have a greater responsibility, as his words and actions are going to count more in the future that they have in the past. Says Dr. Paton: "I do not envy your responsibility. It will require a measure of wisdom and courage that has never been required, and certainly has never been shown before."