- Identifying Limits on a Borderless Map, Richard Falk

- The Law's Response to September 11, Ruth Wedgwood

- The Laws of War: A Military View, William L. Nash

- The " War" on Terrorism: A Cultural Perspective, Fawaz A. Gerges

- The Style of the New War: Making the Rules as We Go Along, George A. Lopez

IDENTIFYING LIMITS ON A BORDERLESS MAP

Richard Falk

Two requirements have governed my thinking about an appropriate response to the attacks of September 11: the urgent need for action that would greatly reduce the threat of future mega-terrorist incidents, and the necessity of recognizing the appropriate legal, moral, and political limits to waging a defensive war.

THE NEED FOR ACTION

In this essay, the need for action is taken for granted, given the gravity of the harm inflicted in the form of an armed attack, thepersistence of the threat posed by the proclaimed intentions and apocalyptic leadership of Osama bin Laden, the demonstrated capability of al-Qaeda to carry out such missions, the dramatic failures of prior reliance on law enforcement techniques to apprehend and punish the perpetrators of major terrorist acts, and the inadequacy of intelligence warnings and preventive actions to provide societal protection. In essence, it would have been impossible for the government of the United States to retain its legitimacy if it had not responded as effectively as possible to the September 11 attacks. Indeed, to retain credibility, sovereign states must demonstrate their capacity to provide security by acting decisively in emergencies to mobilize the relevant resources at their disposal. The difficult challenge was to translate this imperative for action on behalf of security into effective policy directives, given the unprecedented nature of this enemy. It was not a state, but rather a "network" with operational nodes in sixty or more countries, including quite possibly the United States; nor was it formally or openly associated with any particular state or geographical area.

The decision by the Bush administration to launch a war against Afghanistan as the first phase of an effective response was generally convincing. There seemed to be strong evidence of the presence of bin Laden and the al-Qaeda headquarters in Afghanistan, a presence made possible by the Taliban regime. This regime was the embodiment of the most severe variant of Islam ever translated into a governing process, and this oppressive model of Islamic life evidently represented the visionary goal of the al-Qaeda terrorist activity for the entire Muslim world. The Taliban leadership was symbiotically linked to al-Qaeda and its leadership. Osama bin Laden has been quoted on several occasions as expressing his admiration for Taliban-style rule as correctly embodying and prefiguring a desired Islamic political order. There have also been several journalistic assessments, including by Ahmed Rashid, of the degree to which Mullah Mohammed Omar has accepted the visionary orientation toward the United States articulated by Osama bin Laden.1

As of late December 2001, the Afghanistan war had met its major early-stated objectives, seemingly reducing significantly al-Qaeda's capabilities to engage in global terrorism and seriously tarnishing its image as a credible opponent of the United States in the context of a military and civilizational encounter. Although the U.S. government did not rely on a humanitarian intervention rationale, a beneficial side effect of its military operations has been to emancipate the peoples of Afghanistan from cruel and brutal rule, with improved opportunities of rescue from the immediate threat of mass starvation and the deeper conditions of extreme poverty, worsened by twenty-five years of war.

The victory in Afghanistan has by no means extinguished the September 11 threat, but it has decisively weakened al-Qaeda's capacity for mega-terrorist activities originating in Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda's presence was so manifest in Afghanistan that it seemed highly reasonable to hold this particular sovereign state sufficiently culpable to vindicate recourse to war against it: a war that aimed not only to destroy the al-Qaeda presence and to capture or kill Osama bin Laden, but also to destroy Taliban rule. A further goal of the war was to replace the Taliban with a government that would not allow its territory to be used as a base for global terrorism and would be more likely to respect basic human rights.

This fundamental encroachment on the sovereign rights of Afghanistan took place without a specific mandate from the United Nations Security Council, and without much evident consideration by the U.S. government of prohibition by international law on recourse to war. Moreover, there has been no attempt as yet to provide evidence that the Taliban regime was specifically linked to the September 11 attacks, or even possessed advance knowledge of the mission; thus the legal responsibility of Afghanistan is at best indirect, consisting of its having harbored terrorists known to be preparing and training for such missions. The undertaking of war under these circumstances needs to be treated as an exceptional case that does not set a precedent. Unfortunately, in entirely different circumstances of unresolved struggles involving self-determination of peoples, states such as India (Kashmir) and Israel (Palestine) have invoked the U.S. response as validating their own escalation of violence against alleged sources of terrorism, and the United States has acquiesced, or in the case of Israel, provided explicit support. Additionally, Russia and China have been able to intensify their repressive violence against Chechnya's independence movement and Uighur separatists of Xinjiang Province, respectively, without encountering a hint of criticism from Washington. U.S. diplomacy has done little to restrict the response to terrorism to the specific circumstances surrounding September 11.

What the Bush administration needs to stress above all is that it is not beneficial to generalize the justifications for waging war against the Taliban or to minimize the potential costs to world order and international law of a failure to abide by the prohibition on the use of force against a sovereign state. The normative framework of the UN Charter should be reaffirmed: "Self-defense" against terrorism should be narrowly understood, and the procedural obligation to validate uses of force by seeking approval from the Security Council should not be abandoned for the sake of geopolitical expediency. This concern is also relevant to post-Afghanistan phases of the response to September 11, where I do not believe the case can be reasonably made that normal inhibitions on the use of force and respect for territorial sovereignty should be suspended.

Shifting the focus from effectiveness to limits of response brings one immediately up against the unprecedented nature of the threat, and the degree to which its removal challenges the moral, legal, and political imagination. The first difficulty is associated with the interplay between the right of self-defense and the nonterritorial extension of al-Qaeda. As already discussed, it is important to interpret the right of self-defense narrowly in general accordance with the spirit if not the letter of the UN Charter, which in Article 51 restricts self-defense to situations where a state has been the victim of an armed attack. It is desirable to adopt a sufficiently flexible approach to self-defense that allows a state victimized by mega-terrorism in the manner of September 11 to respond in an effective manner even if this means acting outside the letter of international law. Such a basis for response existed in this instance by credibleinference and evidence that the target of military action had a close and indispensable connection to both the harm inflicted and the continuation of the capability and threat to inflict future harm.

The second difficulty is to apply limits in the setting of "war" between a nonstate, transnational network and the leading state, whose geopolitical presence is global. This conceptual complication is novel, and also raises questions about the practical and persuasive relevance of international law and the Charter of the United Nations, both of which have articulated norms almost exclusively on the assumption that rules governing the use of force are based on conflicts between adversary sovereign states; even in the UN setting, the claim of control is further acutely constrained vis-à-vis a superpower (as acknowledged by the veto). What isneeded to endow international law and UN authority with renewed authority is to strike a reasonable and flexible balance between inhibitions on recourse to force and defensive rights, taking into account such new developments as the emergence of global terrorism and the rise of international human rights.

The third difficulty is associated with the wide resonance of the grievances associated with Osama bin Laden's campaign in the Islamic world. To avoid aggravating the threat it is important not to inflame anti-American sentiment further by military overreaction and diplomatic missteps. It is also important to address grievances against the United States, especially those associated with Palestinian self-determination and Iraqi sanctions. A problematic aspect of this challenge is to correct past injustices without seeming to reward terrorism. To beeffective in the long run, a response must address the root causes of terrorism. Emphasizing root causes reformulates the conventional way of thinking about effectiveness, but it also offers a pragmatic rationale for imposing strict limits on the response.

HAVE LIMITS BEEN RESPECTED?

The most useful source of limits is derived from the doctrine of just war, based on the intertwined traditions of religion, morality, and law. The essence of just war thinking is a conditioning of war upon just causes, just means, and just goals. As argued, the September 11 attacks provide ample grounds for establishing a just cause, although the nature of the cause is such that military means of response should be kept subordinate to the extent possible. The nature of just means is determined most authoritativelyby reference to the laws of war and international humanitarian law, with especial attention to the duty of belligerent parties to respect civilian innocence.

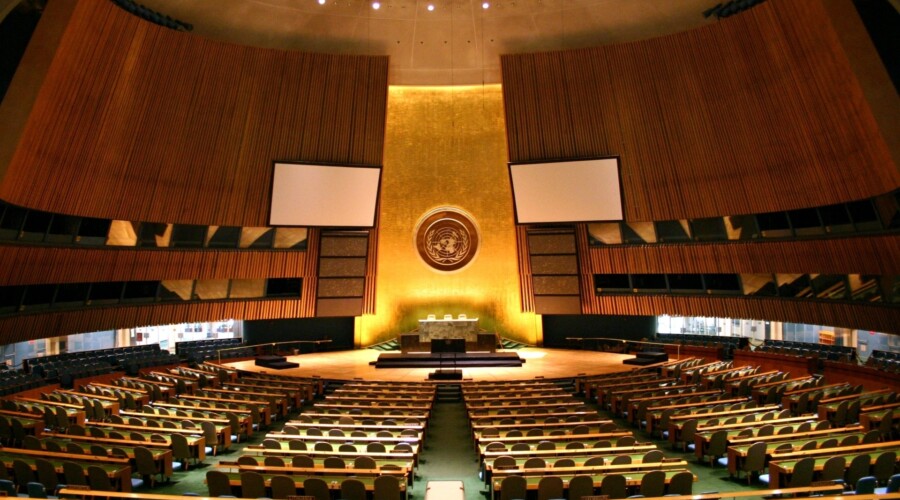

President Bush in his November 10, 2001, address to the United Nations General Assembly asserted: "Unlike the enemy, we seek to minimize, not maximize, the loss of innocent life." Some of the tactics relied upon in Afghanistan raised doubts about the good faith of this claim. The reliance on B-52 bombing, "daisy cutters," and cluster bombs resulted in a large number of Afghan civilian casualties in a context in which the U.S. combat casualties (as distinct from friendly fire and accidents) were zero during this phase of the war, surely raising questions about the way in which the war was fought and the degree of conformity with the laws of war and just means. It should be pointed out, however, that improvements in targeting and guidance technology have made weaponry of the sort used in Afghanistan significantly more accurate than in past wars, and capable of generally limiting direct applications of force to what were believed to be military targets.

Disputes arose as to whether those who planned certain attacks were mistaken about the military character of targets, and thus directed military power against civilians. What is clear, and establishes a crucial moral and legal distance between the terrorism of September 11 and the Afghanistan war, is that civilian casualties were not the result of deliberate actions. That said, more could and should have been done to avoid civilian casualties, even if this meant taking somewhat greater risks of enduring American casualties. The occurrence of civilian casualties, however, is not evidence of departure from the norms of just war. The main objective of just war thinking is to encourage practical morality and to establish strict prohibitions on the deliberate killing of those who are not participating as combatants. At the same time, by allowing the opposing sides to invoke "military necessity" to validate acts that produce civilian harm, there is an acknowledgment that just war may result in extensive civilian death and devastation.

There are two grounds for concern. First, European media devoted far more attention to Afghan civilian casualties than did their American counterparts. As a result, many were left with the impression that the avoidance of such casualties was not an official priority, especially when compared with the huge attention given to Americans who died or were wounded in the combat theater even as a result of accidents. Second, there seemed to be little effort by the United States to use its influence to ensure that its Afghan allies on the ground acted in accordance with international law. The U.S. role in failing to restrain Northern Alliance forces from massacring Taliban prisoners of war, especially in the course of controlling the makeshift prison at Mazar-e-Sharif, has been convincingly criticized by respected European journalistic observers.2

A BROADER MANDATE?

Where the just war framework seems most relevant is with respect to the pursuit of just goals and the extent to which these goals are validated by their genuine linkage to the just cause associated with an effective response to the al-Qaeda threat. In this context, the ongoing debate within the U.S. government and American think tanks about the military extension of the war to Iraq illustrates the problem. To wage war against Iraq would widen the agenda beyond the al-Qaeda threats to encompass countries that are viewed as hostile to the United States. To the extent that a genuine Iraqi threat exists it is not associated with terrorism directed at the United States, but rather with Iraq's posing a regional threat through the acquisition of weaponry of mass destruction and the commission of crimes against humanity in Iraq itself. An extension of the war to Iraq would arouse domestic criticism in the United States, break the impressive degree of international unity supporting the U.S. response to al-Qaeda, and awaken suspicions in the Islamic world that an intercivilizational war was under way despite the reassurances of American leaders to the contrary.

The most plausible interpretation of just goals would limit post-Afghanistan operations to the nonmilitary domains of intelligence operations, cooperative law enforcement, diplomatic leverage, and financial interdiction. In these undertakings the efforts would be directed toward both the identification and destruction of al-Qaeda cells, allowing for some blurred boundaries between al-Qaeda and other political organizations that share al-Qaeda's goals and methods. Such efforts would contribute to the counterterrorist objective of restoring American security and weakening terrorist operations of "global reach."

For this reason, a second limitation of great importance would be to refrain from efforts to destroy political movements that engage in armed struggles associated with limited, national ends. One thinks first of Hamas and Hezbollah. Hamas, in particular, has openly avowed suicidal attacks on Israeli civilian targets, and has caused great loss of life by adopting horrifying tactics, as well as generated acute anxiety about future attacks. But here the context is one in which Israel has also directed its military power in such a way as to wage war against civilian Palestinian society in a manner that relies on modes of violence that are flagrant violations of international humanitarian law and are best conceived of as a species of terrorism undertaken by a state. Hezbollah's main violence was directed at the Israeli army of occupation in southern Lebanon, and does not even qualify as terrorism by most accepted definitions. To suppress Hamas and Hezbollah in the setting of the unresolved Israel-Palestine dispute is to frustrate still further the Palestinian struggle to achieve self-determination, and it would certainly feed the anti-American resentment that already abounds in the Arab world. As a result, it might actually increase the threats of future anti-American terrorism. At this point, although the U.S. government is keenly aware of the nonmilitary aspects of responding effectively to September 11, it has focused almost all public attention on its military response. Such a focus has made sense in relation to Afghanistan, but it will not subsequently. The U.S. government has emphasized effectiveness, but not limits, and it has encouraged a surge of patriotism that is resistant to self-criticism. As a result, there is a tendency to downplay the risks of a military overreaction, and to neglect the challenge of the deeper roots of terrorism. Influential pundit-scholars, most notably Bernard Lewis, have argued that weak resolve by the United States in the past has encouraged terrorists to take bolder action, and that the best mode of response is one that exhibits a maximal resolve.3 But this kind of approach mirrors Osama bin Laden's outlook and could plunge the world into an intercivilizational struggle. We can and must act to avoid this outcome. 1 Ahmed Rashid, Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil, and Fundamentalism in Central Asia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000). [Back]

2 See, for example, Adam Roberts, "Crisis at Kunduz: The Coalition Must Make It Clear That Surrendering Troops Will Be Treated Humanely," The Guardian, November 24, 2001; Editorial Board, World Socialist Web site, "U.S. War Crime in Afghanistan: Hundreds of Prisoners of War Slaughtered at Mazar-i-Sharif," November 27, 2001; also "America's 'Killing Hour'," Wall Street Journal, November 21, 2001. [Back]

3 See Bernard Lewis, "The Revolt of Islam," The New Yorker, November 19, 2001, pp. 50-63, especially pp. 60-63; also Lewis, "Did You Say 'American Imperialism?'" National Review<SPclass=text9 an, October 17, 2001, pp. 26-30. [Back]

THE LAW'S RESPONSE TO SEPTEMBER 11

Ruth Wedgwood

It is hard to watch a society's political virtues mocked as weakness by an uncomprehending foe. The fireball attacks of September 11 against the World Trade Center towers and the Pentagon consumed the lives of more than 3,000 ordinary people—Americans and foreign visitors, businesspeople, secretaries, schoolchildren visiting the Pentagon, travelers flying home. Like Joseph Conrad's terrorist who wished to destroy pure mathematics and settled for the Greenwich clock tower, this was an attack on civil society and global economy, and worst of all, on the innocence of noncombatants.

The jujitsu of the al-Qaeda strategy is its exploitation of the civil values we most care for—the protection of privacy, the celebration of free association and speech, and the cultivation of a multiethnic democracy. Osama bin Laden recruits his young men into militancy in mosques and madrassas, even in the United States, taking advantage of the privacy we extend to religious practice. He has sent his henchmen around the country, to take jobs and gain technical training, using our freedom of movement to prepare his weapons. And he has exploited as cover the varied hues of America's faces, where no group is outside and everyone appears to be local.

Al-Qaeda's hidden target is globalization as well as liberalism. The full integration of the world economy supposes that borders are meant to be freely crossed, and that aliens and citizens will converge in their practical privileges. Yet, of a sudden, national allegiance seems a necessary safeguard against jihad. Borders appear as castle walls to ward off danger. And the ebullient optimism fueling economic growth has taken a tumble, not simply from an oversupply of capital goods, but from an undersupply of fellow feeling. A shared interest in prosperity has not been enough to render benign alienage and the political erasures of borders.

In this unwanted war of the worlds, America's necessary steps of self-protection have not been easy to take. The longtime strategy of treating terrorism as crime rather than war has supposed that the imprisonment and punishment of a limited number of actors would strike fear in the rest, and accomplish the goal of deterrence. We have hoped that the condemnatory label of terrorism would suffice to discourage the violent acts of angry young men in low-growth Muslim countries. But the poor fit of this paradigm has become newly apparent. The punishment of death is victory in a martyr's culture, and imprisonment can be prized as a form of suffering.

We tolerate multiple acts of individual and social violence as the cost of safeguarding our privacy and liberty, demanding that the government meet an extraordinary standard of proof before it can claim any power over our person, acting with a retrospective rather than anticipatory glance. But now the stakes seem different. We are not accustomed to losing thousands of lives in the blink of an eye and the view of a camera. We are not used to the malevolent leverage that lets a handful of men multiply their destructive power through the ordinary instruments of transport and commerce. The deliberate temperance and incompleteness of criminal law enforcement seem inadequate to the emergency, when the threat to innocent life has multiplied by orders of magnitude.

Bin Laden's interest in chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons has been reported for years in the Arab-language press, and recent discoveries in Afghanistan, on the computers and tablets left behind by fleeing al-Qaeda members, has confirmed the frightening agenda. A state has varied linkages and interests to moderate its behavior. But a single-purpose international jihad-a transnational nongovernmental actor of new and malign form-has little reason to stay within any past threshold of violence. We recall with a shudder bin Laden's stated ambition to have a "Hiroshima-style" event. We wonder why we did not take seriously the braggadocio of the conspirators in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, who announced that their real intention was to topple the buildings across lower Manhattan. The newly captured al-Qaeda training manual should further unnerve us, for it instructs its jihad warriors to assume every appearance of normalcy, in order to escape detection within Western civil society. Playing music, shaving beards, wearing gold, associating with women, refraining from open prayer, all are recommended and warranted as legitimate methods of disguise. We may surely wonder how to tell fish from fowl.

We should long ago have acted to shut down bin Laden's training camps in Sudan and Afghanistan—before al-Qaeda had time to train thousands of young men in the techniques of terror. Sudan's offer to hand over bin Laden in 1996 should not have fallen on deaf political ears, with the disastrous decision to allow him to flee to a new lair in Afghanistan. It was a sheer intellectual failure to suppose that admissible courtroom proof, American-style, was the only relevant standard in assessing danger and in justifying necessary acts of self-defense. And even if we were inattentive at first, the deadly cavalcade of events across the decade of the 1990s should have knocked us awake. We wished for a post-Cold War dividend, and ended up cutting the American armed forces to two-thirds of their former size, running our remaining troops ragged in overtime peacekeeping and humanitarian intervention. Our preoccupation with other people's problems in the interventionism of the 1990s, admirable as it was, meant that we ignored the one greatest problem before us—the escalating jihad against American personnel, property, and civilians. The mortuary list spans the full decade: the 1992 bombing in Aden aimed at American GIs bound for Somalia; the 1993 firefight in Mogadishu killing eighteen Army Rangers, staged by fighters trained by al-Qaeda; the 1993 trade center bombing in New York City; the 1995 Riyadh training center bombing; the 1996 bombing of the Khobar Tower barracks in Saudi Arabia; the 1998 East African embassies bombings; the 2000 USS Cole bombing in Yemen; and finally the events of September 11, 2001. Bin Laden seemed to understand the American political rhythm—how much we would tolerate, our difficulty in following patterns, the intervention of worldly distractions. Wistful requests for cooperation from ambivalent governments in the region were not going to turn the tide. Saudi Arabia executed the Khobar Tower conspirators before the Federal Bureau of Investigation could trace their sponsors' methods. Yemen similarly limited the FBI's inquiry on its soil. The symbolic launch of American Tomahawk missiles against bin Laden's training camps in Afghanistan and a pharmaceutical factory linked to bin Laden in Sudan did not hinder his operations, but instead damaged our credibility when American cabinet officers seemed unfamiliar with the basic facts of target selection.

Now, at last, we understand that there is no immunity at the water's edge, and that bin Laden's network is unrelenting in its appetite for confrontation.

For lawyers, the hardest part is in coming to terms with the paradigm shift: that terror can be war as well as crime, and that some of the institutional habits from the past are no longer adequate to the problem. One example is the blindman's bluff that separated domestic criminal investigations and overseas intelligence collection. Bin Laden's terrorist network operated onshore and offshore, yet the two halves of the U.S. government could not share their pieces of the puzzle to allow anticipation in real time. In the aftermath of the 1960s and 1970s, we banished intelligence agencies to overseas collection, to avoid any chance that they could misuse a stateside presence. To complete the firewall, federal criminal agencies were told they could not disclose investigative information to the intelligence agencies, except in limited circumstances—including grand jury testimony (often the best source of human intelligence) and domestic wiretaps. Overseas FBI offices were unable to collect information beyond the limits set by their host governments. In short, no one in the federal government had an integrated picture of al-Qaeda's activities, and the split-brain model was made all the worse when the FBI stopped talking to the White House. The names and aliases, the airplane tickets and apartment rentals, the travel patterns and associations-investigation of which might have allowed us to follow al-Qaeda conspirators as they ventured offshore and back-were unfathomable to a government whose agents were confined to half the picture.

A post-September 11 statutory reform agreed to by Congress and the president newly permits the broad sharing of information between federal criminal investigators and overseas intelligence operatives. It is limited by a "sunset" provision—the statute will expire in four years unless Congress renews it—and it still does not allow sharing with local security officials and foreign intelligence services. But the proof will be in the practice. To intercept attacks we need to act in real time, and the pooling of information must be efficient and practical at the working level as well as in policy circles. It takes a network to catch a network.

There are other more contentious issues in the new approach to terrorism, and it has been salutary to debate them with a full airing of views. Perhaps the most difficult is Attorney General John Ashcroft's decision to permit the monitoring of conversations between a few post-September 11 detainees and their lawyers on a selective basis for intelligence purposes. Why should this ever be permitted? Perhaps because lawyers are often asked to carry messages for their clients. The lawyer's right to disclose an ongoing crime does not solve the problem, since an honest lawyer may not even realize the significance of the message he has been asked to convey. Criminal networks can be run from jail. It has happened in organized crime cases. We take that chance and shelter the lawyers' conversations in ordinary times. But allowing an al-Qaeda leader freely to pass instructions to his outside network portends disaster. Communications used to commit a new crime are not protected, but this also does not solve the problem since the suspect communication will not otherwise be known to public safety authorities absent the monitoring.

Yet the fair trial concerns are also evident. It is fundamental to the constitutionally protected right to counsel that a defendant should be able to confide in his lawyer, without fear that secrets will be revealed at trial. But it is some cause for comfort that like problems have been managed in the past. Even in quieter times, a foreign government office may be monitored for threat-based intelligence purposes while a defense lawyer is representing a criminal defendant at the foreign government's behest. The possibility of overhearing the defense lawyer calling the foreign government office is unwelcome, yet often unavoidable. The usual solution, which has worked well in practice, is to separate the prosecutorial trial team from the intelligence-monitoring team—insulating the trial lawyers from any unfair anticipation of defense strategy or other defense confidences. In the attorney general's order, any proposed sharing of information from the monitoring has to be submitted to a federal judge for review, and approved as unprivileged information.

Another contentious issue is how to handle any members of al-Qaeda or senior Taliban who are captured on the battlefield in Afghanistan. The members of al-Qaeda have violated the laws of humane warfare in their attacks against civilian targets and in their tactic of disguising themselves as civilians. The fundamental rule of armed conflict is that combatants must not deliberately endanger civilians—either by choosing them as targets, or by using a civilian disguise to mask plans for attack. Al-Qaeda has done both. Al-Qaeda has deliberately killed innocent noncombatants in the attempt to spread terror. Al-Qaeda's attacks on military targets are also illegal because they were carried out in civilian disguise. Members of al-Qaeda familiar with its criminal purpose can thus be arrested for conspiracy to commit war crimes.

The current debate in the United States has centered on how to try any such members of al-Qaeda. The president's executive order of November 13, 2001, establishing military commissions as an option for trial was designed to meet three practical problems. First, we cannot afford to have a criminal trial prejudice the intelligence sources and methods needed to monitor al-Qaeda's ongoing activities. In the middle of a war, it may be necessary to close some limited portions of a trial in order to avoid endangering more lives. Second, we may need to consider a broader range of evidence, including some forms of hearsay denied to fact finders in an ordinary jury trial. A compartmentalized conspiracy with a taste for retaliation may not be amenable to the usual more direct forms of proof. And third, the simple physical security of a trial may be hard to assure against a network that is so skilled in mounting military-style campaigns. The American debate on the need for military tribunals has been robust and useful. But it is interesting to note that organizations such as the American Bar Association have come to agree that the modality of military commissions may be necessary.1 The outgoing United States attorney in the Southern District of New York, who has an extraordinary record in trying terrorist cases, has also concluded that ordinary federal court trials may not be adapted to the future practical problems of breaking the al-Qaeda network.2

A privileged prisoner of war is sometimes tried in the same mode as his adversary's soldiers. But al-Qaeda members have not fulfilled the prerequisite conditions of the Third Geneva Convention of 1949—failing to observe the laws of war, or to wear identifying insignia, or to carry arms openly—and may thus fairly be considered as "unlawful combatants." The executive order seeks a "full and fair" trial, and detailed rules for these military commissions are due to be issued. These are consistent with our legal obligations under international law.

The other hard option that must be considered is the wartime prerogative to detain opposing combatants until the conflict is over—even without a trial for war crimes. In an ordinary war, enemy soldiers are interned, under humane conditions, for the duration of hostilities in order to prevent their return to the fight. There may be members of al-Qaeda whom we choose not to try on criminal charges, yet detain as combatants for a period of time. In an ordinary war, it is simpler to identify the enemy combatants because they distinguish themselves by uniform. And in an ordinary war, there is a government to negotiate surrender and soldiers who will obey their government's commands. In the al-Qaeda network, it is less clear whether any leader is capable of deactivating the dispersed cells of actors. The attempt to take "surrenders" from al-Qaeda fighters have been met with renewed violence on several occasions, in betrayal of the promise of peaceable behavior that surrounds the privilege of surrender. It may be hard to characterize when the conflict with al-Qaeda is "over." It is hard to believe that we would contentedly release captured combatants against whom we have strong (if imperfect) evidence of active al-Qaeda membership. In the focus on military tribunals, this circumstance of law and necessity has not been fully addressed, but it may be a condition of the brave new world of jihad terrorism that we simply cannot avoid.

Each war brings unanticipated challenges. With care and deliberation, we must preserve our ethical ideals even while adapting the rules of warfare and criminal adjudication to the new and unwelcome circumstances of al-Qaeda's war against civilians.

1 American Bar Association Task Force on Terrorism and the Law, "Report and Recommendations on Military Commissions," January 4, 2002, available at www.abanet.org/leadership/military.pdf. [Back]

2 Benjamin Weisner, "A Nation Challenged:The Strategy-Ex-Prosecutor Wants Tribunals to Retain Liberties," <Sclass=text11 panNew York Times, January 8, 2002, p. A13. [Back]

THE LAWS OF WAR: A MILITARY VIEW

William L. Nash

I served as a lieutenant in Vietnam. In June 1969, after being in the country for about ten days, I saw my first combat action and it was typically confusing. My platoon was on a reconnaissance mission as part of a larger force when some members of the unit saw a few Vietcong soldiers and began to pursue them through the jungle and marshland countryside. The enemy soldiers were quickly cornered, one was captured, and at least two more cowered in a streambed about 100 yards away. In circumstances I do not fully understand to this day, there was gunfire, many vehicles raced back and forth, and the two radios I was required to monitor broadcast a confusion of chatter. Suddenly, on the higher command radio, I heard the voice of our colonel: "Stop shooting; that's murder," he ordered. The soldiers did stop shooting, the prisoners were secured, and we continued our mission. But that single, short order had great impact on me. It taught me more than any schoolhouse instruction ever could have about the laws of war and how professional soldiers behave in combat.

The war on terror that resulted from the horrific attacks of September 11 has many facets. In addition to the obvious military and homeland security issues, the intelligence, police, judicial, and financial aspects mean there are many "rules" to be observed. It is not a simple process to analyze these considerations. War under any conditions is a gruesome endeavor. But, from the military perspective, the rules of concern are the laws of war as provided by the Hague Convention of 1907, the Four Geneva Conventions of 1949, and the 1977 Protocols to those Geneva Conventions. While there are many other treaties concerning armed conflict, these Big Three provide the majority of regulations. The United States has not ratified the 1977 Protocols, but recognizes the majority of the provisions as "customary international law." The treaties taken together provide a framework by which international armed conflict is to be conducted. Therefore, when U.S. military forces engage in combat, these laws apply. These regulations as a whole address the methods and means of warfare on the one hand, and the establishment of protections for the victims of war on the other. Methods and means include the tactics, weapons, and targeting decisions in war. Primary concerns are the nature of military objectives, the elimination of unnecessary suffering, discrimination between combatants and noncombatants, and issues of proportionality. Protect-and-respect issues include the treatment of civilians, prisoners of war, and the sick and wounded, and the requirements concerning the responsibility of an occupying force.

The principles of the laws of war reflect the driving motivations behind the laws' creation. According to the concepts of military necessity, certain targets are prohibited. The principle governing military objectives stresses that only those persons, places, or objects that make an effective contribution to a military action may be targeted. All combatants must also minimize unnecessary suffering, which is seen as the incidental injury to people and collateral damage to property sustained during a conflict. A crux of these principles lies in the concept of proportionality, which dictates that the loss of life and property incidental to a military attack must not be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage expected to be gained.

The laws of war are not an abstract concept, or limited to customary and conventional laws, but a reality enforced at the highest levels of the U.S. government. A Department of Defense directive signed by the deputy secretary of defense in 1998 mandates that law-of-war obligations are to be observed and enforced; that all violations of the law of war are to be promptly reported, whether committed by or against U.S. forces; and that all components of the military services are to establish an "effective program to prevent violations of the law of war." The directive assigns specific responsibilities within the Defense Department and establishes a formal Law of War Working Group, the purpose of which is to "develop and coordinate law of war initiatives and issues, manage law of war matters . . . and provide advice to the General Counsel on legal matters covered by this Directive."1

In his implementing instructions to the Defense Department directive, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff provides specific guidance to his staff and combatant commanders to fulfill the necessary requirements.2 An example of staff responsibilities is the order to the director of operations to ensure that all plans and rules of engagement are reviewed for compliance with the law of war as defined by the directive. Even more important, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff directs his commanders to establish training and exercise programs to "improve evaluation, response and reporting procedures" and to ensure that the command's legal adviser reviews plans, orders and rules of engagement for the conduct of combat operations.3

The United States Army promulgates its doctrine regarding the law of war in Field Manual 27-10, The Law of Land Warfare</SPAN!. The manual applies the internationally recognized law of land warfare for the actualities of military conduct, providing "authoritative guidance to military personnel on the customary and treaty law applicable to the conduct of warfare on land and to relationships between belligerents and neutral States." It reiterates the belief that the law of land warfare is "inspired by the desire to diminish the evils of war" by protecting "both combatants and non-combatants from unnecessary suffering . . . safeguarding certain fundamental rights of those who fall into the hands of the enemy, particularly prisoners-of-war, the wounded and sick and civilians . . . and facilitating the restoration of peace." 4

The field manual specifically speaksto the "prohibitory effect" of the law of war, limiting the exercise of a belligerent's power from transgressing in those three fundamental areas. With regard to the principles of humanity and chivalry, the law also requires that belligerents refrain from any kind or degree of violence unnecessary for explicit military purposes. Furthermore, the prohibitory effect of the law of war is not superceded by actions borne out of "military necessity," that is, those actions deemed necessary by a state in order to subdue an enemy as quickly as possible. The manual adds that the ideal of military necessity has been "generally rejected as a defense for actions forbidden by the customary and conventional laws of war" inasmuch as those laws have been framed with specific consideration for the concept of military necessity. The manual also emphasizes that the law of war is applicable not only to states, but also to individuals and, in particular, the members of armed forces.5

The best way to illustrate how the United States Army approaches training soldiers on their obligations in complying with the law of war is to list "The Soldier's Rules," taught to all new soldiers in their initial entry training:

Soldiers fight only enemy combatants.

Soldiers do not harm enemies who surrender. Disarm them and turn them over to your superior.

Soldiers do not kill or torture enemy prisoners of war.

Soldiers collect and care for the wounded, whether friend or foe.

Soldiers do not attack medical personnel, facilities, or equipment.

Soldiers destroy no more than the mission requires.

Soldiers treat all civilians humanely.

Soldiers do not steal. Soldiers respect private property and possessions.

Soldiers should do their best to prevent violations of the law of war.

Soldiers report all violations of the law of war to their superior.6 I served as a colonel in Operation Desert Storm. On the morning of February 28, 1991, I awoke at 6:30 a.m. after about three hours' sleep. We had seized our final objectives four hours earlier, and most of the soldiers had had very little sleep for the previous hundred hours. With the day's first cup of coffee, I got out of my armored command vehicle to survey the scene of my tactical command post and to clean up before the very busy workday sure to come. One of the first things I noticed was a concertina wire enclosure approximately twenty-five yards across with forty to fifty Iraqi prisoners of war inside. Two soldiers guarded the prisoners. The Iraqis were sitting on the desert floor in groups of three or four; it was clear that they were tired, cold, and hungry. But before I could act, I saw four American soldiers going toward the prisoners' enclosure with their arms full of blankets and food rations. No orders had been issued; training had taught the soldiersto do the right thing: the right thing according to the laws of armed conflict.

1 Department of Defense Directive 5100.77, DoD Law of War Program, December 9, 1998. [Back]

2 One combatant commander is the commander of Central Command, the organization fighting the war in Afghanistan. [Back]

3 CJCJSI 5810.01A, Implementation of the DOD Law of War Program, August 27, 1999. [Back]

4 U.S. Army Field Manual 27-10, The Law of Land Warfare, July 15, 1976. [Back]

5 Ibid. [Back]

6 Paragraph 14-3, Army Regulation 340-41, Training in Units, March 19, 1993. Guidance with respect to how to teach these rules requires instructors to "stress their military and moral importance." [Back]

THE "WAR" ON TERRORISM: A CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE

Fawaz A. Gerges

Clearly, Osama bin Laden does not subscribe to any international rules in his unholy struggle against the world. The fatwa (religious ruling) issued in February 1998 by the World Islamic Front for Jihad Against Jews and Crusaders-the network of terrorist organizations bin Laden established-holds that "to kill the Americans and their allies-civilians and military-is an individual duty for every Muslim."1 It makes no distinction between noncombatants and combatants, viewing civilians as soldiers in a zero sum confrontation.

Bin Laden claims that targeting American civilians is a legitimate defensive act, because "Muslims believe that the Jews and America have overplayed their hand in humiliating, degrading, and punishing Muslims." Moreover, "these attacks on American targets are legitimate public reactions by the Muslim youth, who are willing to sacrifice their lives to defend their people and Islam."2 The Saudi dissident and his lieutenants further justify their bloody deeds by arguing that the existing international norms are inadequate to address their grievances because, in their view, the United States dominates the system of states and controls its institutions, including the United Nations.

Regardless of its veracity, this assertion sheds light not only on bin Laden's twisted logic, but also on the need to affirm the moral and political importance of existing international norms and rules. In the quick unfolding of events, some observers and policymakers tend to neglect and downplay the importance of this simple but powerful premise, going so far as to advocate changing the rules of the state system by pursuing an ambitious strategy to "end" states or regimes that support terrorism. They argue that if we do not topple the existing regimes that harbor terrorists, we will encourage people who hate us to continue attempts to kill us in appalling numbers; states waging proxy wars are by definition bound by no laws, and combating them on the contrary assumption is to risk entering a one-sided suicide pact.3

This line of thinking fails to recognize that one of the major goals of terrorists like bin Laden is to get rid of the existing norms and rules governing the theoryand practice of international diplomacy. For example, bin Laden has stated that his goal is to destroy the very foundation of international relations and overhaul the system of power politics that punishes Muslims and keeps them down. This is a revolt against secular history and heritage and what he terms Western hegemony over the lands of Islam: "This humiliation and atheism has ruined and blinded Muslims. The only way to destroy this atheism is by Jihad, fighting, bombings that bring martyrdom. Only blood will wipe out the shame and dishonor inflicted on Muslims."4 Originally, bin Laden hoped that in reaction to the killing of thousands of innocent Americans, the United States would lash out angrily and irresponsibly against Muslims, thus precipitating a clash of civilizations. Bin Laden lost his gamble: the United States did not play into his hands by pursuing a strategy that could have pitted the so-called camp of belief against the camp of disbelief. The Muslim umma (worldwide Muslim community) did not rise up and join the fray. Surveys show that 40 percent of Arabs and other Muslims sympathized with bin Laden's criticism of the United States and the pro-Western regimes it supports, but they rejected his terrorist methods. It was only this group's apathy that enabled the activist pro-bin Laden camp to misinform, propagandize, and distort the political sensibilities of other Muslims.5

The Bush administration strategically used international institutions, including the Security Council, to define the September terrorist attacks as an R20;act of war" and to put together an international coalition to attack and defeat the Al-Qaeda organization and the Taliban regime. The Bush administration approach has found many supporters in the international system, including many in the world of Islam. Although many Muslims remain skeptical about the U.S. war against terrorism, they appreciate its narrow focus and limited nature so far. The first phase of the U.S. war against terrorism has achieved its stated purpose: the toppling of the Taliban regime and destruction of the al-Qaeda networks in Afghanistan.

More important, the decisive military defeat in Afghanistan has discredited bin Laden in the eyes of most Arabs and shattered his well-constructed image of holy warrior. Bin Laden lost not only the war on the battlefield but also the campaign for the hearts and minds of the "floating middle" of Muslim public opinion. Even those Arab multitudes that initially flirted with bin Ladenism out of anger with the United States have now discovered that his inflated rhetoric was composed of thin air. However, bin Laden's loss of the propaganda war does not imply that the United States has won. Poll results show that anti-American sentiment is a staple of Arab politics. Today, to be politically conscious in the Arab world is to be highly suspicious of the United States, its foreign policies, its values, and its institutions. For many Arabs and other Muslims the United States has become a scapegoat for the ills and misfortunes that befell their world in the second half of the last century.

The danger lies in the ambiguity of the U.S. strategy regarding the next phase of the war. Will the Bush administration buy the argument of the hardliners and expand the war to Iraq, thus sacrificing the legitimacy principle at the altar of political and strategic calculations? Undoubtedly, the United States possesses the military capability to win wars; yet the real difficulty comes after victory on the battlefield. The U.S. foreign policy establishment should not become so intoxicated with the victory in Afghanistan that it loses sight of the complex realities of world politics with its critical restraining mechanisms. The United States will not be able to win the war on terrorism until it finds the political will to invest in rebuilding decimated civil societies such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, and even Iraq.

Bin Ladenism taps into the Arab sense of victimization and the deep reservoir of accumulated grievances against the United States. With the Taliban vanquished and the al-Qaeda network in Afghanistandestroyed, the challenge facing the United States is to tackle the deepening anti-Americanism in the region by reassessing the efficacy and fairness of its foreign policies. The manner in which the United States conducts the struggle against terrorism will ultimately determine the nature and character of the Muslim response-either resistance or cooperation; it will also determine the potential supply of suicidal foot soldiers to the unholy war waged against the world, not just the United States, by those who subscribe to bin Ladenism.

1 World Islamic Front Statement, "Jihad Against Jews and Crusaders," available at www.atour.com/ news/international/20010928b.html. [Back]

2 See the recruiting tape of Osama bin Laden, which I translated and edited with some colleagues for Columbia University, available at www.ciaonet.org/cbr/cbr00. [Back]

3 See, for example, the thought-provoking essay by Fredric Smoler, "Fighting the Last War-and the Next," American Heritage (December 2001), pp. 38-42. [Back]

4 See the recruiting tape of Osama bin Laden. [Back]

5 See Fawaz A. Gerges, "The Arab Tide Turns Against Bin Laden," Los Angeles Times, January 4, 2002. [Back]

THE STYLE OF THE NEW WAR: MAKING THE RULES AS WE GO ALONG

George A. Lopez

It is curious to note the evolution of discussions about the moral and legal rules that apply in the fight against terrorism. Immediately after September 11, when it was clear that the United States was going to focus its new war within Afghanistan, the first question that arose was how the United States was going to assess the deaths of Afghan civilians as collateral damage. A second, major set of legal and ethical issues developed around the Bush administration's declaration that those captured in the war would face trial before military tribunals. And as the major campaigns of the war have come to a close, the celebrated issue has become the present and future legal status of the quite different fighters, supporters, and operatives of al-Qaeda and the former Taliban government who are in U.S. custody.

The prevailing U.S. government approach to the rules that pertain to these concerns-and to the areas of concern examined by the Roundtable essayists-has been to claim that the unprecedented nature and form of the September 11 attacks warranted unprecedented means in response. In short, new threats and actions by a new enemy demand new rules. At the same time, U.S. government action seems to indicate that as these rules take form and are implemented, they will continue to be adapted to the new circumstances and the ongoing puzzles of this unique situation. Clearly, the United States is developing the rules as it goes along in this war. Such ad hoc rule making has not come out badly for the United States, both as measured against some of the old rules and because the "push" that such new dictates face has not yet come to "shove." But soon it will. And the result will pose more complex and controversial challenges than the new rules developed in the earlier phases of this war. This demands a higher level of democratic discussion about which rules apply to the issues of civilian casualties, military tribunals, and the status of detainees.

CIVILIAN CASUALTIES

The U.S. approach to dealing with collateral damage in the form of the death of Afghan civilians serves as a first area for deeper scrutiny. As President Bush stated in his address to the General Assembly in November 2001, firmly embedded in the U.S. heritage of political and moral concerns is the rule to limit the death of civilian nationals.1 Any fair assessment would conclude that in a number of ways, the first phase of the war was demonstrably more humane-certainly in design, and in much of its execution-than any previous U.S. war-waging enterprise. The commitment to limit loss of civilian life during the massive bombing that opened the U.S. military campaign in October was so strong that pilots often checked with command headquarters in Florida to obtain up-to-date intelligence for certain targets. This practice led some political figures and news analysts to suggest that such efforts were overly scrupulous and may have permitted key members of the enemy to escape. However admirable this behavior during the early phases of the war, as conditions have begun to shift on the ground, so too have the rules that apply to Afghan civilian casualties. Since the installation of the interim government, there have been more civilian casualties per week from U.S. attacks than during the war to overthrow the Taliban. Frustrated by the less-than-aggressive policy of an interim Afghan government to capture and hold former Taliban and al-Qaeda members, anxious over the continued elusiveness of the very top leadership of both the Taliban and al-Qaeda, and still engaged in various actions of a police nature against pockets of resistance, the Pentagon has now selected new targets, many located in more populous areas.

Details about new missions of ground troops and Special Forces are hushed. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld discusses civilian casualties only in response to direct questions about them. Since mid-December these "answers" have reiterated two themes: the responsibility for civilian casualties rests squarely with the Taliban and al-Qaeda as they seek to hide among the general population; and the Pentagon is not going to keep track of civilian casualties or talk about them. The implication is that no one is counting the dead because the numbers do not matter.

The doctrine of proportionality regarding the number of lives lost in war (whether in international law or just war theory) never was meant to be treated as a mathematical equation or an equal balance. But this war situation places the United States in a unique position as more information about the deaths of innocent civilians is revealed. The number of deaths on the U.S. side continues to be revised downward from the initial fear of some 7,000 dead in mid-September to an estimate of 5,000 dead at the World Trade Center and, in early 2002, to just under 3,000 people killed. Meanwhile, the civilian casualties mount in Afghanistan beyond the 4,000 mark in what we are told is necessary action to accomplish war aims. Without critical comment-and certainly without the detailed discussion that has developed regarding military tribunals-the press accepts the unwillingness of the Pentagon to discuss any figures on civilian casualties. Moreover, the press has not been reporting the myriad of alternative sources, from academics through human rights NGOs, that are attempting to record civilian casualties accurately.

MILITARY TRIBUNALS

For all the ambiguity ofdefinition and rules for dealing with those captured in Afghanistan, this "learning as we go" approach may actually be producing clarity and greater consensus regarding the development of military tribunals. Ruth Wedgwood is among those who believe that both prevailing international law and the exigencies of this situation place the original Bush administration proposal on defensible grounds. One reading of William Nash's essay is to interpret these tribunals as a second-best alternative to existing mechanisms already available in the military code of conduct. This difference represents one dimension of what has become-to the surprise of many-a broad-ranging democratic debate about military tribunals.

This debate has blossomed further into an evolutionary dialogue about the political, philosophical, and legal dilemmas associated with military tribunals, with the discussion quickly turning to the potential for modifying the original idea put forward by the administration. The strong critique included a thoughtful analysis by former president Jimmy Carter in early December and a systematic exploration by Human Rights Watch of the costs and benefits of the tribunal compared to viable alternatives.2

In stark contrast to their examination of other aspects of the war on terrorism, such as prisoners and civilian casualties, the concept of tribunals has been seized upon by the media for a wide range of open debate. The venue has ranged from National Public Radio, with its balanced pros and cons, through major and regional TV networks, as well as the press, which have given more than equal time to those who argued that the military tribunal approach was shortsighted. This has resulted in greater caution, a toning down of administration claims about the necessity of such a court, and the "floating" of a range of options.

By January 2002, and with an interim Afghan government in place, the Bush administration was talking openly about modifications that would occur should military tribunals be needed. Thus, without much political fanfare, the indictment, arraignment, and pretrial procedures for the suspected twentieth hijacker of September 11 proceeded without a hitch within the existing U.S. federal court system in Virginia. And John Walker Lindh, whom so many believed would come before a tribunal, was handed over to the U.S. Justice Department to face criminal charges of conspiring to kill Americans. This "learn as we go" approach regarding courts and legal proceedings for the crimes of September 11 does appear more democratized and productive in searching for the best option than do actions in other areas of the conduct of the war. But the results come less from administration leadership and conceptualization than from the steadfast pressure of the broader civil society.

PRISONERS

As I write, in February 2002, the United States has announced that it holds more than 300 members of the Taliban and al-Qaeda as "detainees" and has transferred a number of them to a detention center at the Guantánamo naval base in Cuba. Wedgwood and others argue that much of this action seems consistent with prevailing international law. Human Rights Watch and a host of other NGOs disagree, noting that specific legal and politicaldecisions about the status of these fighters beyond the term "the enemy" or "illegal combatants" or "detainees" must be designated, and that the individuals held must be charged with a particular offense.3 From the Pentagon's point of view, decisions about the legal status of prisoners should be left in abeyance, and the rules governing them covered in generalities. But the circumstances of such prisoners are beginning to defy this approach.

Along the way to defining and seemingly winning the first phase of the war, the United States has developed an identity problem regarding "the enemy" that has led to this current dilemma. By deciding (quite possibly correctly, or at least within the realm of defensible action) that the Taliban’s refusal to turn over bin Laden necessitated bringing down that protective government structure as a means for catching him, and for closing down much of al-Qaeda, the United States mixed two (perhaps three) types of enemies as targets/foes/combatants.

First, the United States attacked the Taliban as an outlaw government that harbors terrorists. This clearly made that government and its troops the enemy of the United States in the (undeclared in a legal sense) war on terrorism. In a declared war, the Taliban and its fighters would fall under the rules of the Geneva Conventions. But U.S. actions seem to counter this designation in favor of a more ambiguous "war" on terrorism, which lends an equally nebulous status to all Afghan fighters and officials captured in that war.

The United States might have opted for a different strategy and enemy designation scheme. The recent history of the international community's dealings with the Taliban provided ample cause for legally grounding U.S. military action in existing Security Council resolutions, thus making Taliban government officials and the Taliban army enemy combatants, who constituted a "threat to international peace." As such, the Geneva Convention rules would apply. But in the absence of such a specification, we await the choice of rules.

This ambiguity may have been best exemplified in the case of Mullah Zaif, the former foreign minister of the Afghan government to Pakistan, who was captured on January 5, 2002. By late February, it was still unclear whether Zaif would be considered a prisoner of war, as a former government official who acted in defiance of Security Council resolutions, or whether he will be protected by the diplomatic rules of various conventions. That he was being interrogated and held was widely known, but his legal status under interrogation remained unclear.

A second interpretation is that Taliban fighters and government officials were the defeated side in a civil war, in which the massive aid and actions of an external nation, the United States, helped the Northern Alliance to topple a government. Under these conditions, international principles that govern the conduct of internal and civil wars, with its own set of Geneva Protocols, prescribe the rules. While it may be neat and convenient to assume that all Taliban fighters supported bin Laden, the truth is that many fighters were first motivated and then captured while fighting under their local warlords, in their own civil war. And ill-advised allegiance is not a war crime, save in a system of victor's justice-which we would assume the United States must avoid.

Third, and most certainly, al-Qaeda members belong to an illegal organization. The rules against them are different from those against Afghan warriors. Surely the United States would not want to withdraw the applicability of the Geneva Conventions from the latter force simply because it was too poor to have uniforms and too poorly led to comprise much of a modern fighting force. Al-Qaeda fighters who are not Afghans can be designated and charged with any number of criminal offenses, depending on the evidence against them. In all cases of current detainees, however, the United States seems anxious to preserve the ambiguous status out of a desire to continue interrogation for intelligence-gathering purposes. <DIVclass=para21Thus we have an ambiguous and varied "enemy" as current detainee, not yet classified as either prisoner of war or criminal terrorist. As the situation develops, two issues heighten the puzzlement regarding why Washington is so hesitant to designate a clear legal status for these individuals. The first is that the actual treatment by the United States of the detainees with regard to food, clothing, shelter, and care regarding religious issues seems to fall well within the guidelines of the Geneva Conventions. What falls outside those parameters is the right to legal counsel, resort to secret interrogation, and failure to provide permanent housing. Second, the quietest, yet most vigilantly concerned, sector of the United States regarding this detainee ambiguity is the U.S. military. These officials and soldiers know the potentially dangerous precedent that the absence of legal designation may pose for U.S. service personnel captured by an enemy in some future conflict. As the debate moves on, these voices may well win concessions and clarifications from Secretary Rumsfeld and the White House that civil society has not yet been able to obtain.

In a style that can only be labeled "making the rules as we go along," the U.S. administration's approaches to the new war on terrorism, from its inception to its current police-style actions, have been modified-sometimes by changing circumstances, sometimes by the heat of criticism or the light of open discussion within the wider body politic. But some areas of the war on terrorism have not evolved so productively. Despite the early U.S. commitment to limit collateral damage, under the interimAfghan government, U.S. forces are killing more civilians than during the air and ground war. Continuing drama and legal ambiguities dominate the holding and interrogation of the diverse fighters and former Taliban operatives who are prisoners of the United States. Only in the area of military tribunals have the wider civil society and the media had an impact on deciding which rules apply to this new war. This may give us some cause for celebrating the virtues of democracy. But the fact that placing the war more centrally within the standards of Western law must be achieved from the bottom up rather than through administration leadership will continue to cause concern. 1 Remarks by the President to United Nations General Assembly, November 10, 2001, UN Headquarters, New York, New York : "We're making progress against military targets, and that is our objective. Unlike the enemy, we seek to minimize, not maximize, the loss of innocent life." [Back]

2 Remarks offered by President Carter at the dedication of the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice, University of San Diego, December 6, 2001; Thomas Malinowski, "Court Martial Code Offers a Fair Way to Try Terrorist Suspects," International Herald Tribune, December 29, 2001. [Back]

3 Thomas Malinowski, "What To Do with Our 'Detainees'?" Philadelphia Inquirer, January 28, 2002; Background Paper on Geneva Conventions and Persons Held by US Forces, Human Rights Watch, New York, New York, January 29, 2002. [Back]