Background & Introduction

In February 1914, Andrew Carnegie established the Church Peace Union, now known as Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs. Carnegie believed church congregations could become the basis of a grass-roots movement to outlaw war. It was his hope that friendship between international church leaders would create bonds of trust that would influence congregations.

Thus the CPU’s first major initiative was an international conference of ministers who would meet at Lake Constance, located on the border of Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, on August 1, 1914. In a terrible irony, however, only three days after the conference was slated to begin, Germany would invade Belgium, drawing Europe and its colonies into the First World War. The outbreak of war meant that many of the men who attempted to attend the conference—from nations now at war with one another—faced delay and sometimes even detention by authorities.

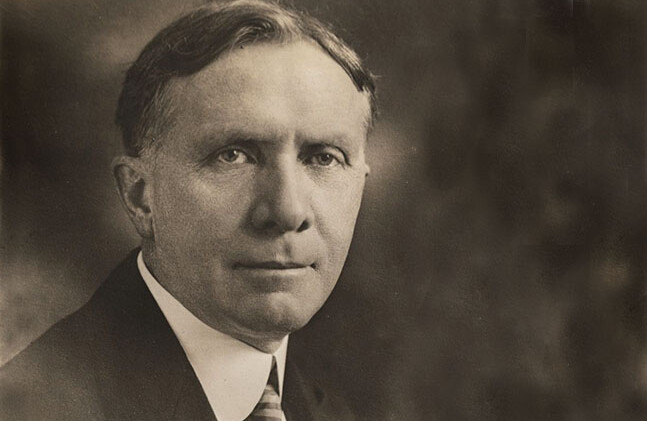

This excerpt from Christian Internationalism (1919), by William P. Merrill, president of the CPU, explains the mixture of despair and hope with which the trustees of the Church Peace Union faced the outbreak of World War I.

Excerpt by William P. Merrill

WHAT relation has this war to the movement toward an international order? How will it, and how does it, affect the coming of that era of organized justice, peace, and good-will for which we long and hope and pray and work?

Judged superficially, the war may seem to be the greatest blow ever dealt the cause of internationalism. It broke the bands that held mankind united. It came as a sudden and fierce negation of all that lovers of humanity had confidently affirmed and expected, a brutal denial of the whole program of international good-will, justice, and order. The delicate fabric of international law, woven so slowly and with such infinite pains, was shattered in a moment.

It seemed a tragedy, or a comedy, according to one's point of view, that just as the war broke there was in session at Constance the first conference of Christians of all nations in the interests of international peace and goodwill. The little group was scattered like a leaf blown before a furious gale. One of the delegates remarked that apparently war could stop a peace conference for more easily than a peace conference could stop war. Some of us recall vividly the wonder and amusement in the faces of the German officers with whom we rode on our way back from that hurried and broken meeting, when we told them why we had come to Constance. Evidently they regarded it as the richest variety of joke that men and women had gone to Germany to hold a peace conference in the summer of 1914.

One of the first men to greet me on my return to America that summer was a friend of the positivistic type, who had always scorned idealistic movements. With an air of judicial satisfaction he said, "Well, I guess you peace people will keep quiet for awhile now."

It may seem the sudden and violent end of all faith and effort in the cause of internationalism. Germany has cast international morality to the winds. She broke the treaty safeguarding Belgium, the law of safety and search at sea, the custom of respect for neutral rights, her own agreement not to use poison gas in warfare, the ancient understanding that trees at least were to be spared—embodied in the old law of the Hebrew people. 1 It seemed as if she had thrown international justice in the scrapheap.

And the other nations followed her lead, compelled to do so in order to meet her attacks. It is a relief to know that, in the matter of the use of poison gas at least, America is technically guiltless, and Great Britain only less so. At the first Hague Conference, proposals were made that the nations agree not to use poisonous gases in warfare. Admiral Mahan put forward a strong argument against such an agreement, and America and Great Britain declined to join in such an understanding. Other nations, including Germany, entered into a positive agreement, however, to abstain from the use of gas. Later Great Britain gave her adherence to the agreement; but the United States never did so.

But the plain fact is that international law and understanding have been violated and broken very generally in the stress of this merciless war. Reprisals have been made, mines sown at sea, vessels illegally held, blockades decalred in violation of the common law of warfare; and it might well seem as if international justice and order had suffered like the invaded territories, the damage being beyond hope of restoration.

But this is only a surface view of the situation. Certain great facts stand out which lead us to declare that this war is, in reality, the greatest forward step ever taken toward internationalism.

Access a digitized copy of Merrill's book

"Christian Internationalism" (1919)

A Moment of Crisis for Responsible Internationalism

Carnegie Council President Joel Rosenthal on internationalism in the 21st century

Read Now