Jameson Spivack, policy associate at Georgetown Law's Center on Privacy and Technology, discusses some of the most pressing policy issues when it comes to facial recognition technology in the United States and the ongoing pandemic. Why is Maryland's system so invasive? What are other states and cities doing? And, when it comes to surveillance and COVID-19, where's the line between privacy and security?

ALEX WOODSON: Welcome to Global Ethics Weekly. I'm Alex Woodson from Carnegie Council in New York City.

This week's podcast is with Jameson Spivack, a policy associate at Georgetown Law's Center on Privacy and Technology.

Jameson and I spoke about facial recognition technology and how it's being used in the United States, with a focus on Maryland. We also talked about how this technology is being used during the COVID-19 pandemic and the fine line between privacy and security when it comes to government surveillance.

For more from Jameson, I encourage you to read his Baltimore Sun op-ed from last month, titled "Maryland's face recognition system is one of the most invasive in the nation."

We also speak about the concept "garbage in, garbage out," which is the title of a publication from the Center on Privacy & Technology on these same issues. You can find that at flawedfacedata.com.

And, of course, for more on AI, surveillance, and the pandemic, you can go to carnegiecouncil.org.

For now, calling in from Washington, DC, here's my talk with Jameson Spivack.

Jameson, thank you so much for getting on this Zoom call today. I'm looking forward to this talk.

JAMESON SPIVACK: Yes, absolutely. Thank you for having me.

ALEX WOODSON: Obviously, the pandemic is on everyone's mind right now, and I want to speak about that a little later in our talk, because I know there is some crossover between artificial intelligence (AI) and facial recognition and what's going on with the pandemic, but first there is a lot to talk about beyond that too. I know this is something you have been focusing on for a while.

I wanted to start speaking about an op-ed that you wrote for The Baltimore Sun on March 9. The headline is, "Maryland's face recognition system is one of the most invasive in the nation." We had Arthur Holland Michel about a year ago speaking about Gorgon Stare in Baltimore, so this is something that the Carnegie Council has been following for a little while. Can you just take us through what's going on in Maryland and why Maryland has a different system than some other states and what exactly that means?

JAMESON SPIVACK: What makes Maryland's face recognition system unique is that federal agencies like Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) can run face recognition searches directly on your photo, even if you have no criminal history. So if you have a driver's license in the State of Maryland, federal agencies can run face recognition searches when they're on your photo, and neither you nor a Maryland law enforcement officer would know that the search was happening, let alone a judge.

In a number of other states that allow the FBI and ICE to access their driver's license photos, the way it works is that they have to send a request to the agency within that state, whether it's the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) or Department of Public Safety, whoever owns that state's face recognition system, and make a request to it. In Maryland these agents can go in themselves. They have a separate log-in. They can log in and run the search themselves. There is no oversight and no accountability because only the person doing the search knows the contents of the search and what they're running on. This is the kind of unchecked federal access that, as far as we know, does not happen in any other state. That's one of the key reasons why Maryland's system is so invasive.

Also, if you look at how it's being used, it includes some very invasive uses. For example, in 2015 during the Freddie Gray protests, police in Baltimore County contracted with a company called Geofeedia, which takes posts and photos from social media and aggregate them and sends them to law enforcement agencies. What Geofeedia did was pulled photos and posts from social media that were posted by people in the geographic area around these protests at key points. They sent these photos to Baltimore County Police, and then Baltimore County Police ran these photos through the Maryland face recognition system to target people for unrelated arrests.

Basically they used a political protest to target and arrest people who have outstanding warrants that were completely unrelated to events at the protest. As far as we know, this has not happened in other states. It may have, but we don't know. This is just the kind of unchecked use that we have seen in Maryland.

ALEX WOODSON: Why is Maryland an outlier in terms of this technology? What is it about Maryland that made it special in this regard?

JAMESON SPIVACK: That's a great question. We're not really sure. It could be that we just happened to get information about Maryland. It could be that this kind of thing is happening in other states, and it just hasn't come out yet. That's what's scary about face recognition; there really is no transparency for the most part.

The way that it came out that police in Baltimore County used face recognition this way was an accident. The American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California did a Freedom of Information Act request, and they uncovered documents from Geofeedia, and in those documents they had a case study about how Geofeedia was used in Baltimore during the protests. They were bragging in this document about how it was used there, and the ACLU said: "Wait a second. This was used during the Freddie Gray protests?" That's how it came to light. Otherwise, we would have never known.

ALEX WOODSON: I'm speaking from New York, and the New York Police Department (NYPD) has used face recognition as well in a couple of cases. One thing that you mention in the op-ed—and it has come up in a couple of places—is the NYPD using Woody Harrelson's photo to make an arrest. I was hoping you could explain that because I think it illustrates a lot of the problems with face recognition technology at the moment.

JAMESON SPIVACK: In this case there was surveillance footage of a suspect stealing a case of beer from a CVS. Police took the security footage, which was really grainy and poor quality.

ALEX WOODSON: This was in New York City.

JAMESON SPIVACK: Correct. They ran his photo from the security footage through their face recognition system. They didn't get any matches. The photo quality was really poor; it was grainy; it was at an angle. These are all things that affect face recognition's accuracy and capabilities. But the officers noticed that the suspect looked to them like Woody Harrelson, so they just pulled up a photo of Woody Harrelson and ran that instead, and this eventually led to the arrest of a suspect.

What this illustrates is that you can take someone else's photo and return you as a result. It begs the question: How accurate is it really if they're using someone else's photo and getting the suspect that they wanted?

ALEX WOODSON: Do you know if that suspect was convicted? Did this evidence hold up in court or anything like that?

JAMESON SPIVACK: I am actually not aware of whether he was convicted or exonerated.

ALEX WOODSON: On the other side of this, there are a lot of cities and maybe states too that have banned face recognition technology for use for crime. Can you speak a little bit about that and what some states and cities are doing differently than Maryland and New York City?

JAMESON SPIVACK: We have seen bans and moratoria on the local level, in a number of cities and towns. At this point in Massachusetts and in California, a number of them have banned or placed a moratorium on face recognition.

We have not seen a full ban or full moratorium at the state or federal level, but what we have seen is a few state bills that have passed that come close, such as in California, where they have a moratorium on face recognition use with body cameras, which is a very positive development, but it's very narrowly targeted to "face recognition cannot be used in by the police wearing body cam." We have seen a number of other bills passed. Most recently in Washington State there is a bill that requires warrants for ongoing and real-time face recognition use. It also puts a couple of accountability measures in place.

We have also seen a number of proposed bills during the current legislative session. I think as face recognition becomes more in the public consciousness, we're seeing a lot more legislative attention. That said, just because of this ongoing crisis, my sense is that a lot of these bills that have been proposed are maybe not going anywhere. In Maryland there is actually a full moratorium bill that was proposed at this session as well as another weaker regulatory bill that is similar to the bill that Washington just passed, but again the Maryland General Assembly is adjourned until May and then they will have a special session, where they're going to focus on COVID.

So there have been a number of bills proposed at this session, and they range from "You just need to put out a report that tells us how face recognition is used"—which is a very weak kind of regulation—to a full-on moratorium, and everything in between. We have seen them all proposed, but they're not likely to go anywhere this session.

At the federal level there are a number of bills that are being proposed. There is the No Biometric Barriers to Housing Act, which would prevent face recognition from being used in public housing for residents living there to access their building. There is a bill from Senators Booker and Merkley, the Ethical Use of Facial Recognition Act, which is a moratorium on warrantless use of face recognition as well as a prohibition on federal funds going to the purchase of state face recognition systems. There are a few others as well, but I'm not able to comment on how much of a chance I think these bills have, given the current crisis.

ALEX WOODSON: I'm trying to think about this from the federal level and from a legal perspective. Is it the fact that this technology is so new that there is nothing there to regulate it? Are there regulations on other types of technology that can be applicable to face recognition?

JAMESON SPIVACK: I don't think it's that new of a technology. In a number of cases it has actually been used for a while. In Maryland they have been using it since 2011. So it's not new necessarily, but it might be new in the public consciousness. It's only over the past couple of years that I think we have seen this backlash against it, and therefore we have seen more attention paid to it by public officials.

There are certain other bills that aren't face recognition-specific—general privacy bills or biometric bills or surveillance technology bills—that might address some of the concerns with face recognition. California has the California Consumer Privacy Act; Illinois has the Biometric Information Privacy Act. These are general biometric or data protection laws. They don't necessarily go far enough in our opinion in terms of protecting against the specific harms of face recognition, but they do address some of the concerns.

ALEX WOODSON: Moving on to the COVID-19 pandemic. We are three weeks or a month into the quarantine phase of this, and things are not looking good for many parts of the United States and many parts of the world. What have you seen specifically when it comes to face recognition and the pandemic? How is the technology being used? What has really caught your eye as far as the pandemic?

JAMESON SPIVACK: This is a developing situation, and at the Center we're researching it and trying to figure it out because it's a very complex question.

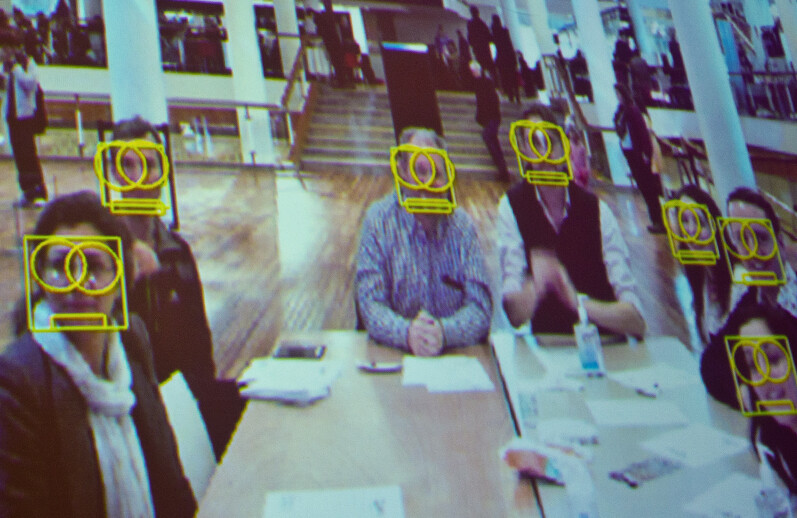

What we have seen is that a lot of the narrative is attempting to be driven by surveillance companies that are selling this technology, and they should not be the ones driving the narrative. There is talk of using face recognition for contact tracing, so if there is an infected person, seeing who they have been in contact with to anticipate who else might have this disease, tracing that person's movement and locations, and seeing where they have been and who else has been there.

To be quite frank, we're at the point where we're beyond contact tracing; we're at the point where we're in full-on crisis mode. We don't even have enough ventilators and masks for people to keep them safe, which is what we need to be doing. We're past the point where contact tracing is as helpful as maybe it would have been a couple of weeks ago. There is also talk of using other surveillance technologies, like heat-sensing technologies to detect fevers, which I am not as qualified to comment on.

Another thing I will say is that it's unclear how face recognition would be implemented at such a large scale. When you use face recognition, you have a photo, and you compare it to a database. It's unclear what database these photos would be compared to. Likely what they would have to do is mobilize nationwide DMV photo data in a completely unprecedented way, so taking driver's license and state ID photos from all 50 states, putting them in a database, and comparing them, which we have absolutely never seen before. That would allow a level of surveillance that is unprecedented.

Any measure that is taken to prevent the spread of COVID that uses surveillance technology, whether it's face recognition or something else, should do a number of things. It should:

1) Be as least invasive as possible, and face recognition is not necessarily the least-invasive way to get this done.

2) It needs to be temporary. There is a temptation to keep capabilities around, especially surveillance capabilities, after the emergency or after the fact. We saw it after 9/11 with the Patriot Act. And enhanced surveillance is kind of sticky.

3) It should also include safeguards against mission creep and derivative use, like taking something that is used for public health and using it to arrest people for X crimes. It should be kept to this use.

4) There should be transparency about how it's used.

5) And it should be restricted to public health. If it's being implemented by a government agency, it should be a public health department; it should not be a law enforcement agency that does it.

These I think are the kinds of measures that should be in place if public health officials decide that some kind of surveillance technology is the best way to deal with this emergency.

ALEX WOODSON: You answered this a little bit just now, but to talk about it a little further—I asked this question in the last podcast I did looking at AI and surveillance and the pandemic: If someone were to argue that this is an unprecedented situation, it's a crisis, and that we need every tool that we can get, where is the line for you between letting the government enter our home—like we wouldn't have before—and the need for privacy and the need to try to have some kind of normal life?

JAMESON SPIVACK: That's a really tricky question, and it's something that we're still thinking through.

As I mentioned before, during an ongoing crisis like this, a public health emergency in which thousands if not potentially even millions of people's lives are at stake, it's not necessarily business as usual. The balance between privacy and surveillance might, for a brief amount of time, be shifted toward surveillance.

We also have to keep in mind that with certain technologies like face recognition, the government has not necessarily shown that it uses face recognition in ways that are accurate or responsible. So it's reasonable to be wary of how they would use it in this kind of emergency.

That said, with any use of something like face recognition in contract tracing or whatever, it's very important that there is a sunset clause, that it's temporary, and that as soon as the crisis is over it goes away. It's very hard because historically that has not happened with surveillance capabilities. So in terms of this line, it's a really hard one, and it's something that we're still trying to figure out.

ALEX WOODSON: For the last question, looking a bit into the future, maybe leaving the pandemic behind for a minute. This came up in a podcast I did on AI a little while ago with a computer scientist named Stuart Russell. His fear was that we could succeed with AI and that there could be all these unintended consequences.

What do you see when you look into the future of face recognition technology? I understand there are a lot of issues now. We talked about the Woody Harrelson issue with the NYPD. From my perspective, I would think that face recognition technology will get better and will get more precise. Would that be a good thing, where you could get this guy who stole beer from a CVS and figure out exactly who he is and go arrest him? Does that concern you, or is that something that we should maybe be working toward?

JAMESON SPIVACK: You're absolutely right that face recognition is improving. In the near future it may get to the point where a lot of the issues in bias or accuracy no longer exist. I want to emphasize that we're not there yet, but we may be there in the future because they are constantly improving.

But it's a double-edged sword. The better it gets, the more accurate and less biased it gets, the more perfect of a surveillance tool it becomes. What this does is it shifts the balance of power between people and government when government has this capability because this technology, especially when it's perfect, gives governments power they never had, and that is the ability to identify groups of people at a distance, in secret, and over periods of time. I can imagine a world in which people are watched and identified as they attend a protest, as we see with the Freddie Gray protests, as they congregate at a house of worship, visit a medical provider, and go about their daily lives. Generally police need a court order to track a location, but face recognition on surveillance cameras allows police to do this without any kind of oversight.

So to me the other side of this is that the better the technology gets, the more accurate it gets, the better of a surveillance tool it gets. At the same time, it doesn't really matter how accurate the tool gets. Even if you input garbage data, you're going to get garbage data out. With the Woody Harrelson example, if you submit a photo of Woody Harrelson, expecting to get someone else, it doesn't really make sense.

There are plenty of other examples also of police officers editing face photos. They take features from different people and mash them together. There is one case where they had a suspect. He had a really big smile on his face, and that pose didn't return any results, so they went on Google and found a pair of lips and pasted those lips onto him. In some states, including Maryland, they can submit composite sketches, artist-drawn sketches of suspects. So it doesn't really matter how good the technology gets. If you're putting in data like this, you're going to get garbage out.

ALEX WOODSON: This is something we're going to be following. Thank you so much for speaking today.

JAMESON SPIVACK: Absolutely. Thanks for having me.