On the morning of October 6, 1976, roughly eight minutes after takeoff from Barbados International Airport, the pilots of Cubana Flight 455 reported an explosion aboard the aircraft, which had started a fire. The plane reversed course, heading back toward Barbados. It never made it. Flight 455 crashed into the sea about five miles from shore. All 73 people aboard, including the entire Cuban national fencing team, perished. It was the deadliest act of airplane terrorism in the Western hemisphere until September 11, 2001.

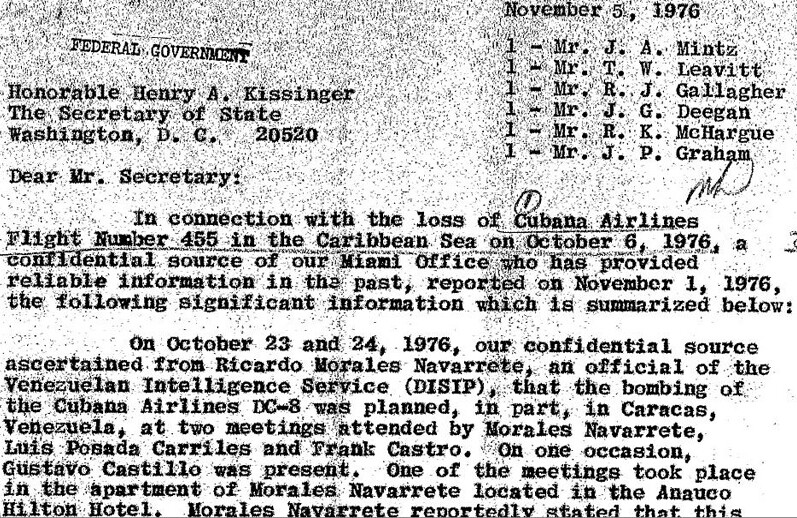

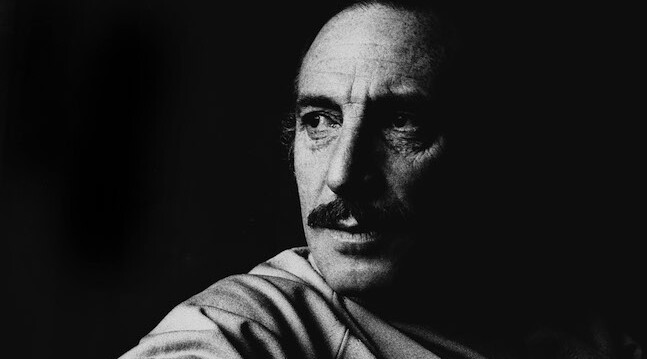

Within days, two Venezuelan men, Freddy Lugo and Ricardo Hernan Lozano, were brought into custody for planting the bomb. But these men, said authorities, were merely the instruments of terror. Indeed, concluded both Venezuelan and U.S. officials, it was Lugo and Lozano's onetime employer, Luis Posada, who helped mastermind the attack. And, as numerous waves of declassified U.S. records show, these officials knew Posada intimately. At the time of the bombing, he ran a large Caracas-based private investigative agency; from 1968 to 1974, he had served in a number of high-ranking positions at DISIP, Venezuela's intelligence service, including as head of counterintelligence; he was also a CIA-trained Bay of Pigs veteran and a notorious anti-Castro Cuban militant.

Posada, who is still widely considered a mastermind of the bombing—as well as the author of numerous other violent acts, including a series of 1997 hotel bombings in Havana that killed an Italian tourist—was never successfully prosecuted for downing Cubana Flight 455. A nonagenarian, he lives today in South Florida.

In October 2017, President Trump announced that he would permit the (legally mandated) release of thousands of previously classified records related to the JFK assassination. These include reams of new documents on the activities of anti-Castro Cuban exiles, including Posada.

These new documents, of which I examined over 1,600 pages, show that the CIA's involvement with Posada was more intimate, multifaceted, and lengthy than previously understood. They reveal, in new detail, the U.S. government's—and, in particular, the CIA's—alarm when it became clear that Posada, their onetime agent, was likely responsible for a major act of international terrorism. These documents also show the complex moral calculus undertaken by the CIA, and other intelligence and law-enforcement agencies, when faced with evidence—long before the Cubana bombing—that Posada was likely involved in acts of freelance terrorism and large-scale narcotics dealing to Miami, while he simultaneously served as a highly-valued Agency asset in Venezuela.

Finally, these new releases call attention to the scourge of systematic overclassification, and raise disturbing questions as to why, other than to save themselves from embarrassment, the CIA and FBI expended so much effort to suppress these documents, which have no discernable relation whatsoever to the JFK assassination.

*** Posada's involvement with the CIA began soon after his arrival in the United States in early 1961. He was a member of Brigade 2506, the CIA-trained Cuban exile army that served as the main expeditionary force during the shambolic April 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion. Afterwards, Posada undertook further U.S. military schooling at Fort Benning, Georgia. He was made a second lieutenant, and received demolitions and intelligence training. New documents suggest he left Fort Benning, and the U.S. military, in early 1964 as an elite U.S. Ranger.

That same year, Posada helped set up and oversee anti-Castro militant training camps in South Florida. While these camps were not directly administered by the CIA, the landowner where the camps were erected "believes he has CIA approval" for them, notes one newly-released document, as "among the instructors are two men trained by the Agency." By April 1965, Posada (while officially working as an auto-body repairman) was again recruited directly by the CIA-this time as part of the Agency's massive, Miami-based anti-Castro JMWAVE program—as "an office of training branch instructor." At this time, he also served as a CIA informant on the activities of JURE (Junta Revolucionaria Cubana), a major anti-Castro group.

As these newly-released documents also show, within a few months of his recruitment by the CIA, the Agency became aware of Posada's problematic penchant for freelance militancy. In 1965 alone, for example, Posada was allegedly involved in plans to blow up Cuban ships berthed in Mexico; recruited to lead a team of Cuban exiles to overthrow the Guatemalan government; and accused of selling grenades, silencers, and bomb parts to a major Miami gangster.

This did not seem to dissuade Posada's CIA handlers, even though, in the words of one intelligence officer, they were aware their agent was involved in "shady deals" at the time. Records show Posada was "amicabl[y] terminat[ed]" by the Agency in July 1967, but began working for them a mere three months later, when he secured a position in the upper echelons of Venezuelan intelligence. (New documents appear to show that the CIA made at least an implicit offer that, should Posada be offered such a position, it would re-formalize their relationship with him.)

And, indeed, as these new documents also show, from 1967 to 1974—when Posada was forced to leave his post in Venezuelan intelligence—he was a highly placed, and highly valued, paid CIA asset, providing secret, weekly in-person updates to his handlers on the internal working of the Venezuelan government, and, almost certainly more importantly, on the activities of other, foreign governments in Venezuela. During this time, noted the Agency, Posada was "in an important and sensitive position in a government of great operational and intelligence value."

Consider the significance, from an espionage perspective, of recruiting a foreign head of counterintelligence—especially one in a country lacking stringent constitutional protections. And Posada seemed to deliver. For instance, he informed the CIA of his plans, as part of a Venezuelan intelligence operation, to break into the Guyanese embassy there; and, later, his intention to bug the Colombian delegation during delicate Venezuelan-Colombian border talks. Posada was also rumored to have total, life-or-death authority over internal security matters regarding Venezuela's sizable Cuban émigré community. These examples surely represent the tip of the iceberg.

Posada's value to the CIA explains its evident strain to minimize his other, extracurricular pursuits. By May 1968, in fact—even as he was working for Venezuelan intelligence—the Agency acknowledged that he was also engaged in "clandestine sabotage activity," that is, freelance terrorism. "Assets are often unsavory individuals," wrote the local CIA station to Washington, by way of a defense. Admittedly, noted Venezuela-based Agency officials, they were aware that Posada was "still capable of engaging in—and here, again, is the euphemism—"independent exile activity."

But not every "independent activity" could be smoothed over so easily. In 1973, the DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration) contacted the CIA about a deadly serious matter: it had surveilled Posada in Florida cavorting with known narcotics dealers, and believed Posada and his wife were involved with smuggling large amounts of cocaine from Venezuela to the United States. If true, this would prove a bridge too far, even for the Agency. As newly-released documents show, while obviously alarmed at this prospect, Posada's CIA handlers did everything possible to delay judgment on their asset's activities, until they could be proven beyond a reasonable doubt. They secretly tapped his phone. They made him take a polygraph, which they claimed he passed. Finally, despite the DEA's deep concerns about Posada's activities, the Agency concluded that, in fact, he was "only guilty of having the wrong kinds of friends."

By mid-1974, however, internal Venezuelan politics forced Posada to leave his counterintelligence job, and the CIA's interest in him waned. (In discussing how to tell Posada that the CIA would stop paying him, his handlers strategized about how best to break the news without "Posada us[ing] his always present .45" on his case officer.) Contact between Posada and the Agency became intermittent, but never truly ceased. He informed them of Cuban exile activities in Venezuela, including the movements of Orlando Bosch, a notorious militant who was considered Posada's co-mastermind in the October 1976 Cubana bombing.

Indeed, as late as February 1976, when his relationship with the CIA was "formally terminated," Posada was passing extremely valuable information to the Agency-including, ironically enough, details about an anti-Castro Cuban plot, in cooperation with the Chilean intelligence services, to assassinate Pascal Allende. (Pascal was the nephew of Salvador Allende, the Chilean socialist deposed in the September 1973 coup supported by the CIA that inaugurated the Pinochet dictatorship.) In June, Posada contacted the Agency about a visa matter. In July, the local CIA station expressed interest in "reactivating contact" with Posada because of his intimate knowledge of anti-Cuban operations in Venezuela.

The bombing of Cubana Flight 455 changed all that. Within days, it was clear to Venezuela-based CIA officials that Posada was "implicated" in the bombing, and the evidence of his involvement only mounted with time. Local CIA sources recounted hearing Posada saying he was "going to hit a Cuban airplane" a few days before the attack. Materials linked to the bombing were found in the offices of Posada's private investigative firm, as were receipts for the airplane tickets of the two men, Freddy Lugo and Ricardo Hernan Lozano—both, again, Posada's former employees—who admitted to planting the explosives.

Suddenly, the CIA's long relationship with Posada had become an acute liability. Even if, as it seems clear, the Agency had no foreknowledge of Posada's plans to bomb the Air Cubana flight, it was true that the CIA had long turned a blind eye to the activities of anti-Castro militants on its payroll. And now, because of this history, the Agency was going to be connected to a particularly vicious act of international terrorism. Unsurprisingly, then, in the aftermath of the bombing, the U.S. government, and the CIA in particular, attempted to disassociate itself from Posada as quickly as possible.

Yet Posada, who was never successfully convicted for his role in the Cubana bombing, once again managed to insinuate himself, inexplicably, into the darker recesses of U.S. foreign policy. According to a recently released 1992 FBI interview (declassified separately from the JFK disclosures), after escaping from Venezuela in 1985, where he was being imprisoned, pending trial, for his role in the Cubana bombing, Posada found his way to El Salvador, where he managed Contra re-supply operations for Oliver North. (Posada, operating under the pseudonym "Ramon Medina," claims that while he was aware that he working for the U.S. government, North's cohort did not know Posada's true identity.)

And his story only gets murkier from here. In 2000, he was arrested in Panama after alleged attempting to assassinate Fidel Castro in that country. He was freed, under irregular circumstances, in 2004. The next year, he snuck into the United States illegally. In 2011, Posada's trial in a Texas federal court, where he stood accused of lying to immigration officials, ended in acquittal. He was permitted to stay in the United States, where he remains to this day.

For years, Cuban and Venezuelan officials have clamored for Posada's extradition to stand trial for the Cubana bombing. This is a faint hope, at best. Even if Posada did not possess his long, entangled record of collaboration with the CIA—a record significantly deepened by these recent JFK document dumps—Cuba and Venezuela, both leftist dictatorships, could never provide Posada the kind of due process to which every defendant is entitled in a criminal trial, or a guarantee that Posada would not be subjected to torture.

Posada will almost certainly die a free man in Florida, taking secrets about the full extent of his relationship with the U.S. government to the grave; Raul Castro and Nicolás Maduro, for their part, will continue to preside over their sclerotic, corrupt, and brutal regimes. It is the 73 innocent people murdered aboard Cubana Flight 455 who will never, it now seems clear, receive the justice that is so obviously their due.