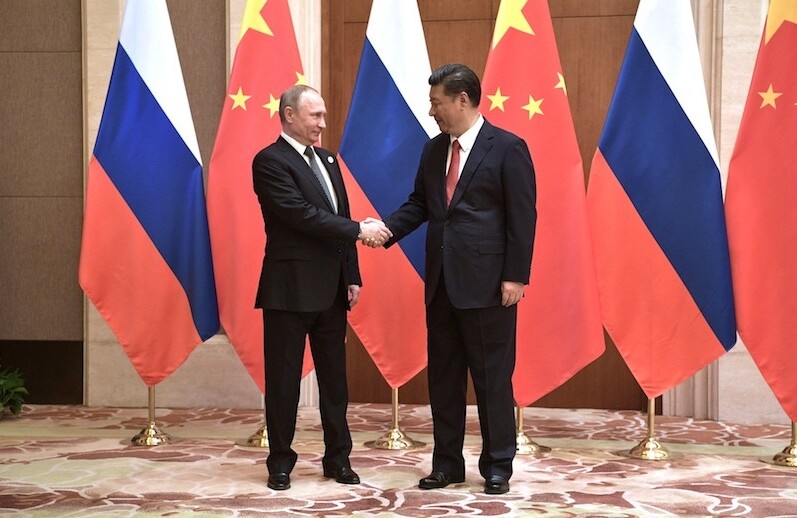

Tom Mahnken and Toshi Yoshihara of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) discuss China and Russia's "authoritarian political warfare." "Not only do they use these influence campaigns, they use economic coercion, occasionally they use a military force, they use non-military instruments of power," says Yoshihara. "And it's the combination of these tools that I think make Russian and Chinese strategy so potent."

Podcast music: Blindhead and Mick Lexington.

DEVIN STEWART: Hi, I'm Devin Stewart here at Carnegie Council in New York City, and today I'm speaking with Tom Mahnken and Toshi Yoshihara. They are both experts based at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) in Washington, DC.

Our conversation today is part of an ongoing series that we're doing here at Carnegie Council on the topic of Information Warfare, how countries influence one another through disinformation, propaganda, and other means. It's also known as "influence campaigns." It goes by many names.

First of all, Tom and Toshi, thank you very much for coming to the Carnegie Council today.

TOM MAHNKEN: Thank you very much for having us.

DEVIN STEWART: Before we get to the topic, your study is called "Countering Comprehensive Coercion: Competitive Strategies Against Authoritarian Political Warfare." That's a lot of C's in there. Can you just tell us a little bit about CSBA please?

TOM MAHNKEN: Of course. CSBA, we're a non-partisan, independent think tank. We focus on issues of strategy, capabilities, and concepts, and budgets and resources. I think we're most effective where we deal with the intersection of those things. We've been around for over 20 years and focus on the future and try to set debates and influence debates on national security.

DEVIN STEWART: Who is the audience of your studies?

TOM MAHNKEN: We have a broad public education mandate, so heavily in the United States, but also we work across the world, particularly with close U.S. allies. We have a set of capabilities that is unique, even in the think tank space, where we have some deep technical expertise but also some innovative strategic thinkers as well.

DEVIN STEWART: Technical in what sense? In terms of budgetary assessments?

TOM MAHNKEN: We have deep budgetary expertise. We also have senior fellows who have deep expertise in land, sea, and air warfare, all sorts of different domains. Also, we have some senior diplomats, and we have a non-resident set of fellows across the globe who enhance our capabilities.

DEVIN STEWART: Let's look at your study. It's about strategies against "authoritarian political warfare," and you explicitly mention the Chinese and Russian governments in the summary of your study. Can you just tell us a little background about why this study? Why does CSBA have this study in the first place? What motivated this study?

TOM MAHNKEN: I would say historically our sweet spot has been in analyzing conflict, whether conventional conflict, nuclear deterrence, and nuclear matters. But it was increasingly apparent to us that conflict has also spread to the information domain. We wanted an opportunity to think about and to study political warfare maybe using some of the tools that we've developed and used in a more conventional realm.

It has also been apparent just from the press of recent events. There has been a lot of press on Russian actions and Chinese actions both in the United States and elsewhere. I think we thought that while reporting and think tanks had done a good job of talking about individual activities, individual tactics, we were missing the forest for the trees, so we saw this as an opportunity to step back and try to think strategically about this phenomenon of authoritarian political warfare.

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: I think what we wanted to study was the commonalities between these various actors and that there are some emerging patterns in terms of their behavior and the things that motivate them to engage in influence operations and political warfare. So we believe that we can develop a broad analytical framework that allows us to study this phenomenon in a systematic way but also to be able to do one of the things that we do very well, which is to subject it to U.S. strategy and allied strategy.

DEVIN STEWART: Before we get into the substance of your findings, are you working with any other partners on this study?

TOM MAHNKEN: This has been an internal study. We are doing some follow-on work, though. We're looking at a whole series of case studies, and we're expecting to have another report coming out in the middle of next year.

DEVIN STEWART: Tell me about the case studies. There are many ways to go about looking at information warfare or disinformation campaigns. You could look at techniques from the country that uses them; you could look at the "transmission lines," so to speak; you could look at the "demand side," so to speak, which is the consumption of disinformation; you could look at the big picture or specific tactics. I wonder even if, since "budgetary" is in your name, that maybe even budgets could be a part of what you look at. What is the methodology?

TOM MAHNKEN: For this report, as Toshi mentioned, we really wanted to focus on the authoritarian model of political warfare. We did separately consider Russia and China, and I'm happy to talk about each of those cases in detail.

I think one of the things that struck us was the commonality between the Russian approach and the Chinese approach. Of course, if you step back from it, that shouldn't be a surprise because both Russia and China, wherever they are today, share a common Marxist heritage and a common playbook that today's leaders in Russia and China can't help but draw from. Even beyond the Marxist heritage, as authoritarian powers I think we found that their governments are quite insecure. They are concerned about domestic populations, so for them political warfare is not just something waged against us and our allies but also a means of internal control, and I think for both the Chinese leadership and the Russian leadership they see the two as interlinked.

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: I think one of the common themes that ties Russian and Chinese political warfare is that they see political warfare as an effort to shape the external environment, to make their near abroad, but also the larger international system, amenable to the nature of the regime. I think that's how you connect their external behavior to the inherent nature of the regime. Because they are so deeply insecure and because they see, for example, the West as an ideological adversary that's out to get them, they believe that they need to have the soft form of power projection to shape perceptions externally to make their external environment safer for these authoritarian regimes.

DEVIN STEWART: The objectives are essentially a soft way of boosting their own sense of security for political stability. Is that essentially how you would describe the objectives of these campaigns?

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: One way to think about it is that this is one element of a larger use of various implements of national power. Not only do they use these influence campaigns, they use economic coercion, occasionally they use a military force, they use non-military instruments of power. And it's the combination of these tools that I think make Russian and Chinese strategy so potent.

DEVIN STEWART: Strategy toward what, though? What are the Russians and Chinese ultimately trying to do with their power? Survive? Is it anything more than that?

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: I think from the Chinese perspective certainly, yes, the basic core motivation is the survival of the Chinese Communist Party, to make sure that the Party can last for as long as possible. But clearly with Xi Jinping in power, Xi has great power ambitions for China, the so-called "China Dream," where he foresees that China will become a great power equal to all of the other great powers by mid-century. So again, influence campaigns, political warfare is designed to create that space in order for China to achieve these grand ambitions.

TOM MAHNKEN: Whether it's China or Russia, even if we're talking about survival, I think for those regimes survival presupposes an international environment or at least an environment in their neighborhood that is conducive to their survival as authoritarian regimes. At the basic level, these political warfare campaigns are meant to get inside other societies, whether our society or those of our allies, and to influence them in a way that's conducive to the Russian or Chinese regimes.

DEVIN STEWART: As we all know, the term "brainwashing" itself was coined to describe Chinese Communist Party techniques during the Korean War. As you mentioned earlier, it's sort of in their DNA to have a strategy toward influencing people's opinions.

TOM MAHNKEN: By contrast, what Toshi talks about, the use of many instruments in an integrated campaign, a seamless passing from peacetime activities to coercive activities, I think both the Russian and Chinese regimes do that and view that as quite natural.

I think we in the West tend to see a clear dichotomy between peace, which is the natural state of things, and war, which is an aberration, with very little in between. Thus, we talk about political warfare, we'll talk about "gray zone" contingencies as a way to wrap our mind around things that come quite naturally to these authoritarian regimes.

DEVIN STEWART: Can I push back on that a little bit because I think a lot of the conventional wisdom is that all governments do this all the time. For example, the Pledge of Allegiance in the United States is a pretty effective and powerful instrument to elicit loyalty toward the United States. Am I reading it right? Are all countries basically doing this to one degree or another all the time with their own people and toward foreigners?

TOM MAHNKEN: It depends on what the "this" is. Also, when you say "countries," it depends on who you're talking about.

DEVIN STEWART: Okay. Let's say big countries.

TOM MAHNKEN: I guess what I'd say is, and I'd even go back to the beginning of the Cold War, when George Kennan, who was then the director of the policy planning staff in the State Department, was looking at what the Soviets were doing. In many ways that's similar to what's going on now. He drew a big contrast, and it's a legitimate contrast, between that unified spectrum of activities that the Soviets were conducting, and what most other governments do.

China, the Chinese Communist Party has funded Confucius Institutes in universities in the United States and across the world. Those are not the functional equivalents of the Alliance Française, for example, which is sponsored by the French government. They undertake different types of activities.

You mentioned the Pledge of Allegiance and you mentioned the United States. I think another commonality between China and Russia, and I would say a stark contrast with the United States and many other Western states, is that they fundamentally have an ethnic view of loyalty. Toshi can speak of this in greater depth in the Chinese case, but it also applies to Russia, where the thought is if you are ethnically Chinese or ethnically Russian, then your primary loyalty should be to China or Russia regardless of where you were born. That's anathema to the American way of life, where you can be born literally anywhere, you can come here, you can become a citizen, you can become a vital part of our society, and you're an American. But the Chinese strategy, the Russian strategy, are both geared toward tapping into those perceived ethnic loyalties.

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: If I can pick up on this issue of the Confucius Institutes, I think one of the key dangers of the Confucius Institutes, aside from the very worthy goal of educating people about the language and knowing a bit more about the Chinese culture and Chinese history and so forth, is a much more subtle strategy of trying to impose in some ways China's worldview. They are trying to shape discussions and shape perceptions that tend to be very favorable to China and particularly the Chinese Communist Party. They've created an atmosphere which encourages self-censorship. I think that's one of the biggest dangers of the Confucius Institutes is that they create subtle pressure points that prevent either visiting scholars or resident professors or students from speaking out about how they view China, and in some ways creating a much more distorted view of China. I think that is something that we need to be very wary about because it goes right after some of the things we value quite a bit, academic freedom and freedom of speech.

DEVIN STEWART: I'm going to push again a little bit because I think it's important to think about the distinction between what we do in the United States and what the Chinese and the Russians do. Can you elaborate a little bit more about how you see American information campaigns in the world and how ours differ from those of Russia and China? I would guess that if the United States could persuade most of the world that the American dream and the American way of life is somehow special and virtuous, we would probably go about doing that in some way or another.

TOM MAHNKEN: Let me draw a couple of contrasts. Maybe one way to contrast things is to actually go back and look at things historically. Go back to the Cold War period, when we did see ourselves in an ideological competition with the Soviet Union and saw a need to respond on the ideological front.

DEVIN STEWART: By the way, we're all School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) graduates, all three of us, and SAIS was involved with what we're talking about right now in Bologna, Italy, and Nanjing, China, as part of a way of persuading people who might be on the fence about capitalism or communism that the free market is the way to go.

TOM MAHNKEN: Sure. Even those efforts, I would say again two things about them: One is, let's stick to the government-sponsored efforts that we undertook during the Cold War. Those were episodic in many ways. There were two periods in particular where the United States seriously engaged in political warfare, and that was at the very beginning of the Cold War and then toward the very end, during the 1980s. You had episodes of seriousness about it.

You also had some real controversies attendant to any sort of government role in political warfare. We did have the U.S. Information Agency, but the U.S. Information Agency was circumscribed in what it could do, what audiences it could broadcast to, and the type of material that it could present. I think that is a real contrast to, say, the long-term Soviet effort that went on during the Cold War.

I would say I partially agree with you, and it's not to say that American society doesn't have a huge influence on the world, but I'd say the vast majority of that influence comes not through government direction, but it comes through Hollywood and through Madison Avenue.

DEVIN STEWART: Rock n' roll, of course.

TOM MAHNKEN: Yes. I would say in many ways our society does what it does because of its very vibrant nature, not because of government direction. And I think that is a stark contrast with both the historical Soviet approach and the contemporary Russian and Chinese approaches. RT exists as a purveyor of information not because it wins in the marketplace of ideas but because of government sponsorship.

DEVIN STEWART: We have Voice of America (VOA), right? We have Voice of America, we have National Public Radio (NPR). How does it differ?

TOM MAHNKEN: Voice of America is outward-directed. It operates under some pretty stark constraints in terms of legal constraints. Even as somebody who has appeared on VOA and is a fan of it, it's not the most well-funded effort, either.

Compare that to the slickly produced RT or China Central Television (CCTV) or the various media outlets that are the outlets of foreign governments or the inserts that find their way into certainly The Washington Post—I can't speak to The New York Times—that are also the product of foreign government-controlled media.

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: One way to think about the distinction between the two, and I think I'm wary of applying moral equivalence to two very different approaches. The American model, if you will, is what has been called "soft power," which is that it's the demonstrative effect of U.S. policy, U.S. actions, and so forth to gain the attraction of those, so people follow the U.S. model because they want to out of their own volition, whereas I think the contrast here is a term that has been called "sharp power," which is really a coercive use of information tools—

DEVIN STEWART: Disruption.

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: —to compel the other side to do something that they would otherwise prefer not to do, which is a great difference between soft and sharp power.

DEVIN STEWART: But sharp power has been criticized. It's not accepted by everyone. Some people think it's vague, and some people wonder whether it's effective. But your research team takes it as a valuable concept?

TOM MAHNKEN: We think it's important to illuminate this phenomenon from a number of different perspectives. That is why we came up with the term "comprehensive coercion" and why we use the term "political warfare" with the word "authoritarian" in front of it.

I do think that there is a distinction between the way that Western democracies have engaged in political warfare in the past and the way authoritarian states have. There are clearly individual national differences as well. We think that the predicate for addressing the authoritarian challenge is to understand it.

DEVIN STEWART: Absolutely. You mentioned a few similarities between Russia and China in terms of these types of strategies or campaigns. You mentioned the slick television shows. You also brought up the Confucius Institutes.

Can you talk a little bit more about the similarities between Russian and Chinese strategies because I think that's quite interesting because a lot of the literature I've looked at has looked at the differences between the two? I'd love to hear about the similarities.

TOM MAHNKEN: There are clearly differences, but we also think there are some significant similarities to include in both cases you have governments using a full spectrum of instruments to pursue their policies.

DEVIN STEWART: The whole of government.

TOM MAHNKEN: The whole of government, which we sometimes aspire to and sometimes in the past have come close to achieving, but they're able to do it; a comprehensive bureaucracy and organizational effort to do that as well; constant and consistent themes and narratives; and this notion that we talked about earlier of a linkage between their domestic population, their diaspora populations, and other outside powers which they see as hostile.

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: I would say that they have a shared history in the sense that both entities have sprung from Marxist-Leninist ideology and the practice of Marxist-Leninist ideology. Organizationally, for example, the Chinese Communist Party is very much modeled under the Leninist approach. One of the key tenets of a Leninist strategy is to engage in a so-called "united front." This idea of the united front was in fact directly inherited from the Soviet Comintern who helped found the Chinese Communist Party. The idea is that you form alliances of convenience, particularly with a stronger power, and then once you join up you try to eat the archrival from the inside out, kind of like a biological virus.

It seems to me that there is this longstanding strategic tradition of thinking about competition in these ways in which both Russia today and China today are inheritors of.

DEVIN STEWART: It's what Fred Iklé called "annihilation from within," which is something we have to worry about, and we have to make sure that we're learning about this and continue to learn about it.

TOM MAHNKEN: Look, we have open societies, and I'd say by and large the fact that we have open societies is a virtue, but these types of authoritarian political warfare campaigns take advantage of the very nature of our societies. We also have multicultural and multiethnic societies. One of the things we need to be wary of going forward is that we don't lose any of the vibrancy and the attractiveness of our society while also dealing with the threats that we face.

Here we're not alone. Toshi and I were both in Australia not too long ago. There is another country that faces particularly a challenge from China and has started to seriously address that challenge, and I think as another multiethnic open democracy there is a lot that we can learn from Australia.

DEVIN STEWART: I'm curious what we should learn from Australia. Of any democracy that has been in the news recently as a should we say "victim" or "recipient" of influence campaigns, being on the other end of it, it has been Australia. What are they talking about there?

TOM MAHNKEN: The Australian government has enacted a whole suite of new legislation which I think will help protect them against some of this malign foreign interference.

DEVIN STEWART: Mostly China.

TOM MAHNKEN: Mostly China, but I think the legislation is neutral to who is doing the interference. Some of that is remedying some deficiencies that Australian law had in areas where we don't have those deficiencies. Foreign political contributions until recently were legal in Australia, whereas they're illegal in the United States and have been illegal for some time.

I think the Australian efforts are focused on protecting Australians, including protecting ethnically Chinese Australians, from outside interference. So I think there is a lot that can be learned from those efforts, particularly as things go forward.

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: I think there are two things that we can learn from the Australian experience. First is the role of civil society and the role of the media. I think the Australian media has done a terrific job in exposing Chinese influence operations, raising public awareness, and also galvanizing the political class to do something about it. Clive Hamilton, who wrote a best-selling book called Silent Invasion: China's Influence in Australia, really brought attention to this problem and did a lot to change the debate in Australian political circles. That's one.

The second thing is to ensure that the Chinese Communist Party does not create a moral equivalence between the Party and the Chinese people, because that's their tendency.

DEVIN STEWART: They're trying to do that.

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: Right, which is that if you attack the Chinese Party, it means that you're attacking the Chinese people, which we then can accuse you of racism. So we need to make sure that when we implement strategies and policies that we make it very clear that the problem that we have is not with the Chinese people, the problem is with the Chinese Communist Party that is seeking to subvert our political system.

DEVIN STEWART: That is an extremely important point, and it has been a recurring theme on these podcasts.

Of course, having control of foreign money coming into your political system is certainly an important thing to look at. But how about addressing "dark money" that finds its way into the political system anyway from foreign sources?

TOM MAHNKEN: I think that's important. If this were back in the Cold War and if the threat was the Soviet Communist Party funding various groups in the West, we actually had government organizations, we had expertise in sorting that out. Of course, we don't live in that world anymore. It's not about Soviet agents with satchels of cash funding the Communist Party of the United States of America or other organizations. It's more challenging.

One of the things I think we need to do is build up in our government the ability to ferret out foreign malign influence. I think there are some cases where the government has a comparative advantage because it would rely on privileged information to be able to trace money flows and so forth.

DEVIN STEWART: Would that be the FBI? Where would that reside?

TOM MAHNKEN: I think some of it is with the FBI. I think some of it could be with other parts of the intelligence community, potentially with Treasury. Rebuilding that competence across the government is important.

Beyond that, I think there are a lot of ways in which non-governmental organizations can play an important role whether it's in Australia or in the United State or elsewhere. I think some of the pioneering work that I'm sure you're familiar with has been done by journalists and by scholars, whether it's Russian malign activity or Chinese malign activity. There has been stellar work done outside of government, and I think that needs to continue. We need to have something like a clearinghouse that highlights this activity and shines the light of truth on it.

In the end, that is what Western democracies do best. It's not trying to out-authoritarian authoritarians, it's to battle untruth with truth.

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: I think a key element of that that is very important in the West is to build up the intellectual capital to better understand the problem because we're only just beginning to grapple with the implications of Chinese and Russian political warfare, and one of the ways that we can better understand the problem is to understand the institutions.

I wrote a chapter in the monograph on the United Front Work Department, which is an obscure, very little-known institution that plays a huge role in waging political warfare. If we can devote more scholarly work to studying the phenomenon, to studying the institutional foundations of Chinese and Russian political warfare, I think that would advance our understanding in thinking about how we can counter them.

DEVIN STEWART: Did your study find any important differences between the techniques that the Russians and Chinese use?

TOM MAHNKEN: I'd say there are differences in techniques, but there are also some differences in goals as well. As Toshi said, for the Chinese these political warfare campaigns are largely directed at building Chinese influence and building an acceptance of China's narrative internationally, and secondarily to counter the United States and counter our allies.

With Russia, certainly, there is an element of exporting the Russian narrative, but I think more of the Russian effort is aimed at creating instability and unrest and creating a negative counterpart to the Russian narrative, so that it is less extolling the virtues of Russia and more showing how Russia's competitors are just a complete mess.

DEVIN STEWART: It seems like you're suggesting that despite the differences they're both comprehensive and strategic efforts by the Chinese and Russian governments.

We recently had the Russia program from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) come visit us here. I believe their description was that in Russia it differed in that it was more like there were some broad orders from the top, but the implementation of those orders down at the bottom on the tactical level was ad hoc and entrepreneurial.

Is that the sense that you get from looking at Russia's approach, especially with the 2016 election in the United States?

TOM MAHNKEN: I think it's a fair characterization. I think the closer you look at China—and Toshi is the real expert on China and not me—you could also probably detect entrepreneurial behavior.

DEVIN STEWART: Do we believe that Putin said, "Go get Trump elected," or do you think it was something like Putin said, "Try a bunch of different things and see what happens"?

TOM MAHNKEN: I think there is a good question about what Putin was seeking to do, whether it was have a preferred outcome or create doubt. It's hard to say. As a scholar and a recovering policymaker, it's hard to say.

DEVIN STEWART: That's like 20 years in recovery, right?

TOM MAHNKEN: That's right.

Those are areas where I think governments and government intelligence organizations can speak with the greatest authority. But when it comes down to patterns of behavior and patterns of deception, that's I think where scholarship can really make a difference together with shining a light on areas where these campaigns are going on where we may not even be aware.

Getting to our current work, we're looking at a number of case studies including Chinese malign influence in the South Pacific, in New Zealand, where Anne-Marie Brady has done some outstanding work as a New Zealand scholar, but also looking at Chinese influence in the compact states of the Western Pacific which are, at least some of them, U.S. territory.

We tend to think of these influence campaigns going on elsewhere. They're also going on in U.S. territory and are targeting American citizens as well.

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: I think there's no question from the Chinese perspective that it is very much driven from the top. President Xi Jinping formed a small leading group dedicated to the waging of united front strategies. This was his personal direction to revive this idea of the united front and make it a central component of his strategy and of China's foreign policy.

In terms of implementation I think what's interesting is that what we read in the media is typically at the national level, national-level universities and so forth with regard to the Confucius Institutes, but I think many of the actions are also taking place at lower levels, at state levels. So I think increasingly we do need to look at Chinese influence operation at the municipal levels, influence in state universities, and how are they affecting towns and cities across the United States. I think that's going to be one of our key challenges in the coming years.

TOM MAHNKEN: If I could say one more thing on the case of Russia. I think it's unfortunate that the topic of Russian malign influence has become so politicized that it is very difficult to have a dispassionate discussion of the topic. As we move forward and as we increasingly face the topic of Chinese malign influence, I think one of the things that's very important is to keep this topic as depoliticized or as bipartisan or as non-partisan as we can because if we fail to do that, then that's yet another case of our open democracy working against us and ultimately working against safeguarding the American people against these types of threats.

DEVIN STEWART: There was a huge article in The New Yorker recently. It was like a book review on a brand-new book coming out, a very innovative book from an expert on these types of campaigns. The title of the book is Cyberwar: How Russian Hackers and Trolls Helped Elect a President—What We Don't, Can't, and Do Know, and it's looking at the case of the 2016 presidential election. The author's conclusion is that, yes, indeed, Russian meddling tipped the scale toward Trump's direction, put the thumb on the scale, so to speak. Yet that conclusion is extremely contentious and very controversial.

My question to you is: Where do you all come down on how effective these types of strategies by authoritarian states to conduct political warfare are? How effective are they? I can imagine a very well educated, smart, worldly person coming across some of these things online or on TV or whatever and just dismissing them as ridiculous. But that might not always be the case. How do you all see it?

TOM MAHNKEN: Let me succumb to the historian in me and look back at how effective or ineffective these things have been in the past. That's where I think we can with greatest certainty judge these things. If we go back to the Cold War, at a time when Soviet propaganda was to American eyes, as you say, to sophisticated American eyes, oftentimes clumsy and sort of ridiculous. Even in those cases oftentimes it acquired believers in the United States, but even more significantly believers abroad to include in the developing world. In a number of cases Soviet propaganda, Soviet active measures worked against American interests, even very clumsy forgeries that on the face of it weren't plausible at all.

I think we dismiss efforts like this at our peril because even if we, sitting here having this conversation, would find a particular tactic to be unsophisticated or clumsy, that doesn't mean that others will. If there is one thing that I take from the current information age, it's that information, whether it's accurate or inaccurate, is pretty hard to get out of the system. It just keeps rattling around.

I would say that it would be a mistake to characterize either current Russian or current Chinese efforts as clumsy. I think they're much more sophisticated. That gives me real pause in thinking about these things.

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: I think the Chinese have been quite effective just in terms of influencing the way we talk about China. They've had a huge impact on the way the discourse has taken place, both in the public but also at the highest levels of the U.S. government.

One of the things I think we've succumbed to is that we've been socialized and normalized into accepting certain party lines, for example, this idea that if we did anything to harm engagement, then we are certainly engaged in a Cold War mentality or we're seeking to contain China, and therefore in polite company, in polite circles these are not the kinds of things that you should be talking about. I think the Chinese have been very effective in shaping our perceptions and in influencing the way we even talk about China. I think that's quite effective.

On the other hand, I think it is important that we pay attention to areas where they may make mistakes, where they may be too high-handed or overreaching in terms of their rhetoric, and we should go after those things. While they have been effective writ large, I think we should pick up on their weaknesses or mistakes that they make in this area and exploit them to our advantage.

DEVIN STEWART: It's been very interesting. Before we go, Tom and Toshi, anything you'd like to add or anything in terms of policy recommendations that you'd like to leave behind with us?

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: I think one of the things that have been left off the conversation for too long is the ideological dimension of the competition and that again in polite company we don't want to talk about the authoritarian nature of the Chinese regime. We would prefer to talk about the Chinese Communist Party as a transactional partner, as a business partner that we could do business with.

Increasingly as the threat becomes clearer I think we need to look at the Party for what it is. It is an authoritarian regime seeking to maintain a monopoly on political power, and it will do many things and go to great lengths to maintain that monopoly on political power. If we begin to talk about and think about China in ideological terms, I think that might give us some options in terms of a counter-strategy.

TOM MAHNKEN: I think these are authoritarian regimes that are seeking to get inside of the fabric of our society and divide Americans from Americans. I think that point needs to be hammered home repeatedly.

What this is all about ultimately is our way of life, our open way of life, a broad view of what the United States stands for. If we allow—and it goes back to the earlier point about the 2016 election—ourselves to be divided and to question our democratic institutions, then we're giving comfort to authoritarian regimes that in the end wish us ill, and they wish us ill because—as Toshi said—our existence and the very vibrancy of our society poses a threat to those regimes. We should never let that stray too far from our minds.

DEVIN STEWART: Tom Mahnken and Toshi Yoshihara from CSBA in Washington, DC, thank you so much for coming today.

TOM MAHNKEN: A real pleasure. Thank you for having us.

TOSHI YOSHIHARA: Thank you for having us.