TV Show

Highlights

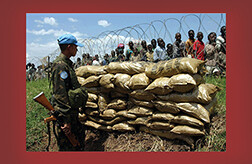

Why do international peace interventions often fail to reach their full potential? Based on 15 years of research in conflict zones around the world, Autesserre shows that everyday behavior, such as the expatriates' social habits and actions caused by lack of local knowledge, strongly influence the effectiveness of many peacekeeping operations.

ALEX WOODSON: Good evening and welcome to the Carnegie Council. My name is Alex Woodson. I am the program coordinator for Carnegie New Leaders. Thank you all for coming out tonight. We have a great event on conflict resolution and international intervention.

I would first like to thank Julian Harper for helping Stefanie and me to organize tonight's program. Julian is a research analyst at Franklin Templeton Investments. He is a board member and treasurer of Sure We Can, a Brooklyn-based nonprofit serving New York City's cancer community, and he is co-chair of the Children's Museum of the Arts' Young Professionals Committee. He is also a member of the Carnegie New Leaders Steering Committee and an honorary trustee at Carnegie Council.

Julian, the floor is yours.

JULIAN HARPER: Thank you, Alex.

First off, thank you all for coming tonight. It is really a great pleasure for me to introduce Séverine Autesserre. Séverine is an old friend. She is an assistant professor of political science at Barnard College, a highly respected thought leader and scholar in international relations and African studies, focusing on humanitarian aid, civil wars, peacebuilding, peacekeeping, and African politics.

Her work fits particularly well with the Council's mission and ethos, given her focus on some of the world's most problematic conflict zones and her quest to find best practices that bring lasting peace.

Séverine's research in the Congo, where she has worked regularly since 2001, culminated in her Grawemeyer Award-winning book The Trouble with the Congo: Local Violence and the Failure of International Peacebuilding, published by Cambridge University Press in 2010. The book also won the International Studies Association's 2011 Chadwick F. Alger Prize.

Séverine has won numerous other fellowships and prizes, and her insights have appeared in leading academic journals. She has been a consultant to a variety of humanitarian and development groups in Afghanistan, Nicaragua, Kosovo, India, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Her recent book, Peaceland,examines international peacekeeping interventions and their shortcomings to date. Based on several years of ethnographic research in conflict zones around the world, focused on the DRC, but also drawing on comparative research in Burundi, Cyprus, Israel and the Palestinian Territories, Timor-Leste, and South Sudan, it demonstrates that everyday elements, such as the expatriates' social habits and usual approaches to understand their areas of operation strongly influence peacekeeping operations and their effectiveness.

With that in mind, I will turn over the floor to Séverine to tell us more about Peaceland and some of her innovative prescriptions to better help host populations build a sustainable peace. Thank you.

RemarksSÉVERINE AUTESSERRE: Thank you so much, Julian, for the introduction. Thanks so much to the Carnegie Council for organizing this event and for inviting me. And many thanks to all of you for coming. It is really a pleasure and an honor to be here.

Tonight I would like to speak about one of the Centennial themes of the Carnegie Council, war and reconciliation. How can we end violence? How and why do former enemies reconcile and eventually decide to create shared institutions? What are the ethical demands of peacebuilding in societies divided by war?

My own research and my new book, Peaceland, focus on what international actors can do to help with the peacebuilding and reconciliation process and, more specifically, on the ethics and practice of peacebuilding in conflict zones.

I have spent the past 15 years studying international peacebuilding initiatives, mostly in the Democratic Republic of Congo and also in various other African and non-African countries. During this field work I constantly witnessed a puzzling pattern: international interveners kept using, reproducing, and perpetuating ways of working that they themselves viewed as inefficient, ineffective, or even counterproductive.

By peacebuilding I mean any and all actions that help promote peace during and after a conflict. So when I say peacebuilding, I include all of the actions that diplomats and United Nations officials often categorize as peacemaking, peacekeeping, or peacebuilding.

By interveners I mean expatriates who work in peacebuilding, including donors, diplomats, peacekeepers, other United Nations or African Union staff members, and the foreign staff of international and non-governmental organizations.

For instance, it is now conventional wisdom that local ownership is essential for successful peacebuilding, but local stakeholders are rarely included in the design of international programs. Scholars and practitioners frequently emphasize that using universal peacebuilding templates is ineffective and that context sensitivity is crucial. And yet, interveners often use models that have worked in other conflict zones but are not appropriate for the specific local conditions.

Local people, and the interveners themselves, deplore the expatriates' tendency to live in a kind of bubble, where they interact mostly with other expatriates and where they lack contact with host populations. And yet, this phenomenon still recurs in virtually all areas of intervention.

Why? The persistence of these inefficient modes of operation is all the more puzzling because interveners, as you know, are not indifferent or callous. Most of them do care about the effectiveness of their actions. They are not stupid—most of them are intelligent, well-read, well-educated people. They are not immoral—most of them go to conflict zones animated by strong moral values, to help people and countries affected by violence. And they are not even oblivious to the consequences of their standard practices—some of them are actually very uncomfortable with the way international peacebuilding operates on the ground.

Why then do interveners contribute to perpetuating modes of operation that they know—that we all know—are inefficient, ineffective, unethical, or even counterproductive?

What I also found striking when I was in the field is that a number of individuals and organizations ignore, or even actively challenge, the international interveners' dominant practices, and they suggest alternative modes of operation. The existence of these exceptional cases raises two questions for me: first, what can we learn from them in terms of increasing the effectiveness of international peacebuilding; and second, why haven't they managed yet to convince their colleagues to adopt the alternative modes of operation that have proved to be more effective? Identifying the factors that impact the effectiveness of international peacebuilding is of critical importance to scholars, to practitioners, obviously to people living in conflict zones.

Admittedly, international efforts can succeed only when warring parties are ready to stop using violence and when local, national, and regional peacebuilding capacities are strong enough to make peace sustainable. But despite their limitations, external contributions can make the difference between war and peace. There have been a number of studies at the micro level and at the macro level that have shown that international support significantly increases the chances of successful peacebuilding.

So when we look at the explanations for the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of international peacebuilding, we see that they focus on, for instance, material constraints—whether or not peacebuilders have enough funding to implement all the projects that are necessary to reestablish peace. They also focus on vested interests, as in peacebuilders prioritize either the pursuit of peace, which promotes peacebuilding effectiveness, or they prioritize the pursuit of their own personal national, organizational, or professional interests. As a result, their project effectively promotes these vested interests but they have little effect on the actual construction of peace.

The last kind of explanation focuses on the imposition of liberal templates and values. Many scholars argue that Western liberal values orient interventions towards strategies that are inadequate and that are inappropriate to local conditions, and that this leads to peacebuilding failure, while efforts and international interventions that are contextually sensitive are much more effective.

What I found in my research, and the central message of my new book Peaceland, is that the everyday dimensions of international peacebuilding efforts on the ground also strongly impact the effectiveness of intervention efforts. By everyday dimensions I really mean mundane elements, such as the expatriates' social habits, standard security procedures, or habitual approaches to collecting information on violence.

I also look at the influence of the informal and the personal on formal professional initiatives. In my research I demonstrate that everyday practices shape the overall intervention from the bottom up. They enable, constitute, and help to produce the macro-level strategies, policies, institutions, and discourses that other researchers usually study. They also explain the existence and perpetuation of ways of working that interveners themselves widely view as inefficient, ineffective, or even unethical and counterproductive. I want to clarify from the start that my approach and existing explanations are not mutually exclusive but, instead, they are complementary.

Another important point is that my argument is not that we should eliminate support for international peacebuilding altogether. There is, in fact, wide consensus among scholars and host populations that external support and external expertise are often—not always, but often—necessary for successful peacebuilding. Foreign peacebuilders have a number of distinct advantages in conflict zones, and I am happy to elaborate on each of them during the discussion if you are interested.

So what we need is not to forfeit these contributions but, instead, to think about how we can increase the effectiveness of international efforts. I make this argument in my book by drawing on several years of ethnographic research in Congo as well as briefer research visits to South Sudan, Burundi, Cyprus, Israel and the Palestinian Territories, and Timor-Leste. I also draw on my previous life as an intervener in Afghanistan, Kosovo, Congo, and Nicaragua, and obviously on a lot of practitioner reports and academic writings on other international interventions.

In the remaining time, I am going to devote most of my time to explaining how interveners construct knowledge of their areas of deployment. I will trace the impact that this process of knowledge construction has on peacebuilding effectiveness. Then I will very briefly identify the everday elements that make possible the specific dynamics of knowledge construction and that create very firm boundaries between interveners and local populations. And again, I will trace the impact that these everyday elements have on peacebuilding effectiveness. I will conclude by summarizing the implications of my analysis.

Let's trace how interveners understand their areas of the planet, how they come to know their areas of deployment.

The first thing to do is to focus on the struggle over what and whose knowledge matters in Peaceland. In the current international system, the most valued expertise is that of interveners trained in peacebuilding, humanitarian, and development techniques, and with extensive experience in a variety of conflict zones. In contrast, although there are exceptions, the knowledge of country specialists is much less valued and the knowledge of local people is usually trivialized.

International and non-governmental organizations, just like diplomatic and donor missions, usually do not rely on anthropologists or historians who could help interveners gain an in-depth understanding of their work environment. Instead, they hire operational experts who have done the same technical jobs before. In terms of promotion and status, intervention structures value the number of missions in different countries rather than the amount of time one spends in a particular mission. In fact, the interveners who stay too long in a specific place are considered to have "gone native" and they are thus discredited.

The consequence is that, of all the expatriate peacebuilders that I met, only a few had preexisting knowledge of their countries of deployment. All of the others had been hired on their substantive and technical capacities.

Valuing thematic knowledge over country-specific expertise results from various social dynamics, including the process of professionalization of international peacebuilding, which has increased the effectiveness of intervention programs on the ground.

However, valuing thematic expertise over local knowledge also leads to standard ways of working in the field that decrease the effectiveness of intervention efforts. For instance, it legitimates the deployment of people who do not speak any of the local languages, even though on the ground everyone identifies the interveners' lack of linguistic ability as one of the main obstacles to effective peacebuilding. And it leads to high turnover among interveners, which has a lot of negative consequences, such as loss of institutional memory and a lack of understanding of local context.

Even more importantly, valuing thematic expertise over local knowledge asserts the superiority of the international staff, who are viewed as having the consequential knowledge over local employees.

In virtually all aid and peacebuilding organizations, whether diplomatic, international, or non-governmental, expatriates are in management positions and local people make up the staff. Very few local people make it into leadership positions in their countries of origin. If they want to move up the hierarchy, they have to go abroad and become expatriates.

Let me tell you a story that illustrates how the very fact of being local changes the way interveners relate to a person and his ideas. One of my interviewees, Michel, was a Congolese businessman (he is still a Congolese businessman). Michel is from a mixed background. He has Belgian, Portuguese, and Congolese ancestors. Michel was frustrated by the way interveners behaved toward him and toward other Congolese elite. He felt that interveners were talking down to local counterparts and that they did not take local ideals into account.

So, during a meeting abroad, Michel conducted an experiment. Instead of introducing himself as Congolese, as he usually did, he pretended that he came from Puerto Rico. The attitude in the meeting, he said, was completely different. He had much more credibility and much more influence when he passed as an outsider.

Another consequence of the fact that thematic expertise matters more than local knowledge is that intervention structures very rarely solicit local input in the design and planning of their efforts. This approach creates resentment among local populations and it is at the root of the phenomenon of local contestation, resistance, and adaptation that leads to the failure of so many projects and programs.

Of course, local actors frequently resist international programs for their own benefit, for instance, to pursue their own personal economic, political, or security interests, or just because they don't care about building peace.

But not all local people have these kinds of vested interests. Instead, most of them would benefit from more stable conditions, and many of them truly care about building peace in their countries.

So we need to understand why the people who would benefit from successful international efforts instead reject or distort them. The main reason is the premium that interveners place on thematic expertise over local knowledge.

In all of the countries in which I worked, local stakeholders complained that international peacebuilders were arrogant and that they provided aid in a humiliating manner. My interviewees emphasized that the arrogance resided in thinking that the international ways of working are better than the local ones and in failing to pay attention to local ideals.

What is really interesting for those of us who are interested in peacebuilding is that I heard this kind of criticism against all kinds of international programs, not only those that were obviously shaped by liberal values—programs that, for instance, insist upon organizing elections—but also those that had no relationships with liberalism, such as programs that build foreign rather than local models of toilets to respond to water and sanitation emergencies.

My interviewees were very clear. They said that they do not resist or reject the international programs because of their content, such as the supposed Western or liberal characters of the programs; instead, they reject the very act of imposition, regardless of whether or not they like the strategies and the values that the programs convey.

The international and non-governmental organizations that fight against this trend are excellent illustrations of the advantages inherent in valuing local knowledge on par with thematic expertise. The few comparative evaluations of these efforts that I know of show that these organizations are much more effective at promoting programs that are locally owned and locally supported and, thus, effective and sustainable.

We then wonder how in these circumstances the international peacebuilders, those that are not exceptions, make sense of their environment. Interveners face multiple obstacles when they try to collect and analyze information on their countries of deployment. This results in a lack of understanding of local conditions.

One of the key consequences of the lack of understanding of local context is that it entices international peacebuilders to rely on simple and often overly simplistic narratives to design their intervention strategies. Adopting dominant narratives offers a useful way out of the predicament that international peacebuilders face, given the poor quality of the information and analysis that they have.

Dominant narratives emphasize a few themes on which to focus. Interveners can then believe that they have a grasp of the most important features of the situation instead of feeling lost and deprived of the knowledge that they need to properly accomplish their work.

But let's look at the impact of the dominant narratives on, let's say, the Congolese conflict to see what the perverse consequences of this practice are. In 2010 and 2011 when I conducted the research for this project, and still even now, three narratives oriented the general discourse on Congo and shaped the intervention strategies there. These narratives focused on a primary cause of violence, the illegal exploitation and trafficking of natural resources; a main consequence, sexual abuse of women and girls; and a central solution, reconstructing state authority.

These narratives achieved prominence because they suggested straightforward explanations for the violence. They also suggested feasible solutions, and they resonated with foreign audiences.

Thanks to the reliance on these dominant narratives, the Congolese activists and international activists have managed to put the Congolese conflict on the agenda of influential decision-makers in national capitals and headquarters. So that's great.

But, unfortunately, the reliance on these dominant narratives and on the solutions that they recommended have often led to results that clashed with their intended purposes, including an increase in human rights violations on the ground.

The focus on mineral resources has diverted attention from other causes of violence and thus has decreased the overall effectiveness of the international peace efforts.

The focus on sexual violence has raised the status of sexual abuse. It has transformed it into an effective bargaining tool for combatants and has increased its uses.

And finally, the focus on statebuilding has merely enabled the Congolese government and the Congolese army to become more effective perpetrators of human rights violations and other kinds of abuses against Congolese people.

A number of Congolese individuals that I interviewed for this project, along with the exceptional individuals and organizations that I mentioned before, have tried to reintroduce more complexity in the discourse on Congo, but thus far without success.

Various everyday elements make possible the counterproductive practices, habits, and narratives that I just mentioned. These elements include the expatriates' personal and social experience living and working in conflict zones, the patterns of social relationships among interveners and between them and local populations, the interveners' standard security routines, their advertisement of their actions, their search for neutrality and impartiality, and their focus on quantitative and short-term results. I won't elaborate on each of these elements now, for the sake of time. I am more than happy to do that during the discussion if you are interested.

But what's really important to keep in mind is that all of these everyday routines have intended consequences, such as enabling interveners to function in conflict zones and enabling their organizations to help the host country build peace. But these routines also have unintended consequences. Notably, they construct and maintain a firm separation between expatriates and local populations, thus decreasing the overall effectiveness of international peace efforts. They also perform, make visible, and reinforce an image of the interveners' superiority over local populations, which these populations strongly resent, and again, that leads to resistance and rejection.

Again, the individuals who challenge these personal and professional routines, who develop personal and social relationships with their local counterparts, who forgo standard security routines, and who maintain a low profile and avoid advertising their actions—these people end up implementing programs that are much more effective.

In sum, my new book suggests a new approach to the study of international peacebuilding, an approach focused on the everyday dimensions of international peacebuilding on the ground in conflict zones.

This new approach produces findings that are different from those of existing research. While existing research emphasizes the differences among interveners, my research highlights commonalities among them. And in contrast to people who study the imposition of liberal values, I show that these commonalities reside less in shared ideas, such as shared adherence to liberal values, but they lie instead in the everyday practice of peacebuilding on the ground.

These new findings suggest a fresh answer to the question of what affects the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of international peacebuilding. Macro-level policies, strategies, institutions, and discourses are not the only determinant of peacebuilding effectiveness.

The everyday practice of peacebuilding on the ground also matters tremendously. It is by looking at these everyday practices and habits that we can understand why interveners contribute to perpetuating modes of operation that they know are ineffective, inefficient, unethical, or counterproductive.

Everyday practices, habits, and narratives are perfectly understandable responses to the daily difficulties of intervening on the ground in conflict zones. They enable interveners to function in the difficult environments that they face. But they also have unintended consequences that decrease the effectiveness of international efforts.

In conclusion, let me mention extremely briefly the policy recommendations that I have developed based on this analysis. Again, I am more than happy to elaborate on that afterwards.

Interveners could rebalance the role of local and thematic knowledge by following the model of the exceptional organizations that I mentioned during my presentation. Concretely, that would mean changing recruitment and promotion practices for interveners, relying more on local employees, creating tools and structures to involve communities in novel ways, and also creating tools and structures to gather input from the intended beneficiaries.

In addition, we could break the boundaries between interveners and local populations by creating structures for better relationships between expatriates and their local counterparts, by promoting socialization between interveners and local people, and by convincing interveners to forgo standard security routines and the requirement to advertise their actions. Local people could further help break these boundaries by changing the way they routinely interact with foreign interveners.

This is a very brief summary of a 350-page book and of 15 years of research. I would be more than happy to elaborate on any of my points during the discussion if you are interested. Thank you.

QuestionsQUESTION: Thank you. Galymzhan Kirbassov from Peace Islands Institute.

Thank you for that presentation of your research and book. I think it contributes to the literature of understanding the peacebuilding significantly. I have two points.

One, when you raised the question that people who are hired for peacebuilding purposes by the UN are mostly expatriates and have very little local knowledge, I think that is actually one of the hiring policies of the UN Department of Political Affairs for peacebuilding. They are specifically hiring outsiders so that they are kind of impartial towards the conflict in the zone, so they are not one side or another side. They think—I don't know; it's arguable—it is more effective than hiring someone from one side or another side.

The second point is your methodology of research is very unique and of course contributes to understanding. But I think it can be used only in studying current conflicts or the current peacebuilding efforts or the efforts that are coming up in the next years because you cannot—I don't think it is applicable to the past peacebuilding efforts—or is it?—because you need to have interviews and lots of field research. So how would you use the technique to explain past peacebuilding efforts?

SÉVERINE AUTESSERRE: Thank you. I will answer your two questions in the same order.

Yes, it is a policy of the United Nations and of many non-governmental organizations and other international organizations and diplomatic missions. It is a general policy to hire outsiders because, again, of what I was saying, this idea that thematic expertise matters more and because we think that local knowledge doesn't matter.

What I am saying is that, yes, you need to have outsiders, you need to have people who are impartial, and you need to have people who have not been involved in the conflict. But if you have people who have no knowledge of local conditions, then they are never going to be able to help mediate a conflict productively.

You also need to have people who understand what is going on. You can have local knowledge whether you are an outsider or whether you are an insider. There are plenty of people who write Ph.D.s on different countries or who were born abroad but then move to a country, like that country, and decide that they are going to start trying to learn much more about that country. So you can have outsiders who still know more about local conditions than the usual thematic experts that we see deployed in conflict zones.

So what I am saying is I agree with you that it is a policy. I think that it is a bad policy. What I am arguing is that we should change this policy. I am trying to convince people at the United Nations and in other organizations that, yes, it is great to continue to hire these people, to have these impartial mediators, but we should also hire other people, because thus far it is completely lopsided. We have one kind of expertise, which is great, but which is not sufficient. So we should bring in the other kind of expertise into the organization so that then as a team both the impartial mediators and the people with insider's knowledge can help resolve conflicts. That is going to be much more productive.

On whether the findings are applicable to the past, as I was saying, it is based on 15 years of research. Of course, when I was in Kosovo in 2000—it's a long time ago now—I didn't think about how my everyday practices impact the effectiveness of my actions. I thought that I was doing great. I was not.

But that's the thing. It's because, with hindsight, I realized that what I was doing, what I was seeing my friends do, 15 years ago, 10 years ago, when I was in conflict zones, that was actually detrimental to our action.

But we didn't even think about it. We thought: "Who cares who I'm going to have a drink with at night? Who cares how I am going to talk to this person who is really annoying me because it's the 10th time that he is coming to my office and I've told him that I didn't have time? It's not really important. These are everyday things that really don't matter. What matters is the high-level policies, what is decided at the headquarters, whether or not we are going to have funding, and it's the kind of programs that we are designing."

Then, with hindsight, I realized that: "No, actually what I was doing on an everyday basis was just as important and just as influential." I really believe that.

Then I went to read reports and memoirs and everything I could find on things that were happening in the past 15 years—I don't know in the 1990s. But on things that happened in the past 15 years, I strongly believe that the analysis is relevant to analyze what was going on before.

As to whether it can help change what is going on in the future, yes, it can.

I think part of your question was also can we find these people with local knowledge and with local expertise. Yes, we can. I have plenty of Ph.D. students who are doing country-by-country-based analysis and who will be looking for a job very soon. Some of them are already looking for a job.

I have plenty of students who want to start studying a country, but they're like "Well, I don't want to focus too much on a specific country because what I need is to learn about election organization in general or intercultural conflict management." But if they know that when they graduate there are going to be positions open for people with the kind of expertise that they want to acquire, then they are going to become experts on a specific country, they are going to learn the language, they are going to learn the history and the culture.

So we already have this expertise. It's just that these people are not being hired. If we need more—which I think we will need more if we have a big change in the way we hire people—then it will be a snowball effect and a virtuous circle. The more people see job openings for people with country-specific expertise, with knowledge of local languages, local history, local culture, the more they will want to study specific countries, specific languages, specific cultures. Then we are going to get the people we need in the positions that we need.

QUESTION: You argue that so many people who are trying to do so much don't understand the local culture and, as a result, are not as productive. Doesn't it sometimes happen that people do understand the local culture, but they find the local culture inconsistent with the liberal values they are trying to impose? When they see women not treated properly, it conflicts with what they believe in, and so what appears to be a lack of understanding of local culture is really the fact that the local culture is inconsistent with the liberal values they want to promote.

SÉVERINE AUTESSERRE: Yes, you are entirely right. That's the one thing against my analysis for which I haven't found a good answer. So thanks for asking that question today.

There are some times when there is such a clash between the local cultures, as you say, either in terms of the status of women or sometimes the status of children—whether, for example, you can have children participating in armed groups—or, in terms of democracy, in basically the right political organization, but people just don't want to listen to it.

I agree that when there is a conflict then there is no good solution. Then you need to have a clash between the international donors basically and the local stakeholders.

But what I am saying is that this happens in fact very rarely. When you look at the number of times that you have conflicts within a peacebuilding organization or when people reject a peacebuilding or a humanitarian or a development program, very often it is not a matter of a clash of values.

It is really a matter of you just trying to impose your things on me and you didn't ask me what I wanted. So, for example, you give me a school. "I don't want a school. I have already five schools. What I need is a hospital. So I am not going to use your school because it is unhelpful, and I am going to steal money, I am going to steal the mortar from your school, I am going to steal everything, so that I can help build the hospital that I want."

That is really not a clash of values. It's just a problem in designing the program. You have that for peacebuilding programs very often as well. I have heard many times of non-governmental organizations, for example, organizing reconciliation projects but forgetting to ask, or not understanding who were the people to bring in to these reconciliation projects. So they would organize forums and then the people who arrived were already friends: "Oh, that's so cool. We are going to have one day, we can eat and drink together." So the reconciliation project was not reconciling anybody; it was just bringing in people who already were getting along completely fine together.

So again, you have clashes of values sometimes. I wish I could have statistics to tell you it's only 5 percent or it's only 2 percent. I don't because it's impossible to have these kinds of statistics on a worldwide level. But based on the anecdotal evidence that I have, it is really a minor percentage of all of the clashes that we have between international peacebuilders and local populations.

Already, if we fix the 95 percent of the problems that are not related to a clash of values, then that will be a huge step forward. Then someone else can try to find a solution for the problem that you raised.

QUESTION: Hi. My name is Morten Christensen. I am from Denmark.

Thank you for a great presentation. As a student, this summer I had the opportunity to go abroad for two months to work as a peacebuilder. I think your observations are right on. Everyone is in the same bar every night, everyone knows each other, the same sort of dynamics as you'd expect from life here in New York.

Two points. One goes to the question of local knowledge versus international knowledge. Because the field of peacebuilding is still quite nascent, I find there seems to be some sort of pendulum dynamic quite often, where as soon as someone comes up with a new buzzword, everyone is kind of running in that direction and they will be running that word for a certain period of time, then they will run the other way as soon as someone comes up and says, "Hey, that's not working."

One of them is around this phenomenon of local knowledge. I would ask if you have any thoughts on how to avoid romanticizing local knowledge, because we shouldn't be blind to the fact that once you go in and you find your expert, this expert is quite likely to have interests, or at least have a certain perspective. If local knowledge is perfect, then why are we there in the first place? That's one question.

The other question is to the observation that people, even though they are people who go abroad, still have aspirations for personal successes or they have interests—they work for themselves or for institutions . . . if you could say a little more about that.

What do we do with it? How do you translate that into better practice?

SÉVERINE AUTESSERRE: Yes, we shouldn't romanticize local knowledge at all for various reasons. First thing, as you mentioned, there is not one kind of local knowledge. When you arrive on the ground, you realize that there are many local knowledges and that some of them are actually very different from one another. The local experts will all have different kinds of expertise, and sometimes the expertises are in conflict with one another.

And also, local practices are sometimes oppressive, they are anti-democratic, they are sometimes not—women do not have the place that they should in society. The people who are in power or who are the experts are sometimes the very people who caused violence in the first place. So yes, there are a lot of problems with local knowledge.

That's why I think we need to have outsiders come in, and especially outsiders with country expertise, because these people will be able to tell you, "There are these different kinds of local knowledge, so we should make sure that we take them all into account when we design our programs."

A country expert will be able to tell you, "This person is advocating for this specific program, saying that he is a local expert, but in fact it's because his brother lives in that village, and so he has an interest in getting a peacebuilding action in that village or in getting the headquarters in that village, or whatever."

Or they will be able to make sure that when there are different groups and when the society is very fragmented, as happens most of the time in conflict zones, then everybody is taken into account when we come in.

That's why I really see a role for outsiders and that is why I am not saying that we should eliminate support for international peacebuilding. There is a role for outsiders, and especially for outsiders who have enough understanding of the local context that they can help us see what is problematic with the existing local practices and that they can help tailor the program to get around these challenges.

On people working for themselves or for their institutions, when I started thinking about the policy recommendations that I could make based on this analysis, one of my colleagues told me, "You have to construct a system without thinking that your system will be populated by angels." That's exactly it.

So I started thinking: "Okay, imagine that I have the person who doesn't really care about peacebuilding, doesn't really care about the population. How can I make it worth it for these people to do the things that I want?"

That's why I spoke about promotion practices. Currently, you do not have any kind of accountability to beneficiaries, so when you are evaluated as an intervener, the kinds of local networks that you have developed is very rarely taken into account. Whether or not you speak the local language is not going to help you get a better job; it is not going to help you get a raise. Whether or not you get along well with your local counterparts, whether you socialize with them, etc., etc., is not taken into account. Whether or not you have learned the history and the culture of the place is not taken into account.

I am saying if we can add that to the standard evaluation package and have that taken into account when people are thinking about promotions and thinking about who is going to get the higher jobs, that is going to give an incentive to people who are working for themselves, for their own self-interest, to actually acquire more local knowledge.

The same thing I was saying for recruitment. If we put more emphasis on increasing the understanding of the country, then it is going to give an incentive to people who work for themselves to acquire this understanding of the country.

For security routines what I did—basically the problem with security routines is that interveners often live in a compound, they live behind very high walls and barbed wire, which sends a lot of really bad messages to people outside. It sends the message: "I'm scared of you, I don't want to interact with you, and I'm so valuable that my life has to be protected so much more than your life." Lots of bad ethical messages.

Now there has been research on the security of humanitarian aid workers by people like Jan Egeland and Abby Stoddard. What they have shown—and it is fascinating—is that what they called the "acceptance" approach to security is actually much better to promote people's security, to keep you safe in conflict zones.

The acceptance approach is basically trying to have relationships with all of the communities and all of the armed groups around you. Developing good relationships with all of these people is possible in all of the conflict zones; there are organizations and individuals that do that. Again, very difficult to have good statistics, but the ones we have show that people who use this acceptance approach are safer and they have fewer security incidents and the security incidents are less bad, than people who live in bunkers and who try to isolate themselves from their environment.

Again, that is something for your person who works only for himself or herself. Well, if I tell this person, "You are going to be much safer if you go out, you interact with the local population, you go and have a drink at night with all of these people—or not drink if you are in Afghanistan, or you drink orange juice—if you try to integrate in your community, you are going to be safer than if you don't," again that is going to be a really good incentive for that person.

I really tried to craft all of my policy recommendations, again not thinking that I have angels in the system—although there are some angels, but there are a lot who are not—thinking that we have nomal human beings in the system and that they want to work for themselves as much as they want to work for others.

QUESTION: Thank you for a really great presentation. My name is Eddie Mandhry. I'm a Carnegie New Leader.

This year we marked the 20th anniversary of the Rwandan Genocide. Is there anything that you might be able to say about the politics of non-intervention?

SÉVERINE AUTESSERRE: Thank you for your question. The politics of non-intervention is something I have been thinking a lot about for this project. Basically, when I drafted the first part of my book, my thought process was about everything that was wrong with international peacebuilding on the ground. At the end, my conclusion was we have to stop doing that because we are doing more harm than good. So I was basically advocating for non-intervention.

Then I started presenting my research to a lot to people I had interviewed and to local people and to international peacebuilders on the ground and here in New York and in other capital cities, and I realized that I was wrong.

I realized that there was a lot that international actors could offer—expertise; resources; plugging into international networks, ideas of what has worked in other situations that are similar and that could be useful on the ground; impartiality, someone who is outside of the conflict and who is less sensitive to pressure, less sensitive to blackmail, who is not biased, who has more credibility. There is a lot that international actors can offer. So I completely revised the book.

And also, the more I have worked, the more I think that there are people who do things right. There are really people who know how to do peacebuilding in a way that is respectful of local populations, in a way that takes into account local inputs, and in a way that really improves things on the ground for people affected by violence.

So I have moved away from my stance on no, it is better not to intervene, to a stance where I am saying sometimes we do more harm than good, but we have to be aware of what we are doing, we have to correct that, because we can do so much good. We can help so much people who are affected by violence, and because we can have this impact, we absolutely have to increase the success of our efforts, because otherwise it is a huge missed opportunity.

ALEX WOODSON: Thank you to Séverine, thank you to Julian, thanks to everyone for coming out tonight. This has been a great event. We have lots of events coming up. Thank you all.