In this fascinating conversation, Thomas Pogge explains how growing up in post-war Germany awakened him to injustice. He lays out his plan for reforming the pharmaceutical industry, and much more.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: I'm Julia Taylor Kennedy, program officer here at the Carnegie Council. Welcome to everyone in the room and those watching us on the webcast today. I'm really looking forward to our town hall discussion.

Thomas Pogge and I will chat for 25, 30 minutes and then we'll open the discussion to you all. So let's get started.

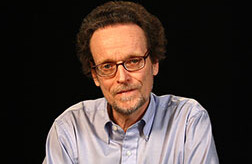

Many talk about values or morality in global matters, but few are as steeped in the theory and practice of ethics in international affairs as today's speaker, Thomas Pogge. He's a political philosopher who applies his ideas to the field of development economics. After earning a diploma in sociology at Hamburg University, Pogge began his scholarly career at Harvard, under the wing of the esteemed justice theorist John Rawls. Ph.D. in hand, Pogge went on to refine and defend Rawls's ideas in two books, one published in 1989 [Realizing Rawls] and another in 2007 [John Rawls: His Life and Theory of Justice].

He has since turned his attention to global poverty and global health, promoting the Health Impact Fund, an alternative system of pharmaceutical innovation and access to medicine for the developing world.

Pogge is on faculty at Yale University and he also holds posts at the University of Oslo and the Center for Professional Ethics at the University of Central Lancashire.

I could fill the rest of our time telling you about his various other accolades and affiliations, but I'm really eager to let him get in on this conversation, so we'll begin.

Thomas Pogge, welcome to the Carnegie Council.

THOMAS POGGE: Thanks, Julia.

RemarksJULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: Let's start with what drew you to the study of ethics, political philosophy, justice.

THOMAS POGGE: It's always hard to answer questions about one's own biography, but I think the first sort of big thing that I remember from childhood is waking up and finding myself living in Germany, in a country that had just gone through some horrendous thing. As a kid, when you grow up, you feel the world is normal and these adults are all wonderful people. You take your cues from them. You trust them.

I gradually learned that something really very extraordinary had just happened here. Lots of people had been murdered. There had been a horrendous war that Germany had visited on the rest of the world. All the people I thought of as models, role models, adults, had been in some way or other involved in that—my teacher, my parents, everybody.

It was an amazing awakening. As a kid, you sort of struggle with that. I lost for a while all trust in adults. I felt that they talk a good line, but how do you really know it's true?

One tremendous experience was, I was in a flower shop at age seven or so, and I said, "How do I know that these flowers are not suffering, tremendously suffering? They've all been cut off. The parents say that the flowers don't suffer, but how do I really know that?" This was a reaction to this experience of losing faith in adults.

So this gave me a kind of anti-authoritarian leaning early on. That was reinforced in 1967. The shah came to visit Germany, and lots of students were beaten up by people he brought along—bodyguards, so-called, 50 or 60, who beat up the students. The police watched and did nothing.

Then the Vietnam War—America had been a big role model for me. I was in love with America for a long time, until they made this horrendous war in Vietnam that was on every evening news and so on.

So it was events of that sort that got me involved in politics and justice issues.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: Then how did you get from Hamburg to Harvard?

THOMAS POGGE: That's sort of embarrassing. It was totally contingent. I was studying sociology. I knew very, very little about philosophy. The woman I was living with at the time was a psychologist. We were members of some elite honor society, where we had a year abroad coming to us.

We said, "Where are we going to go?"

She said, "Oh, we have to go to Berkeley. That's the best place for psychology."

I wanted to go to Oxford because I sort of liked the architecture.

So we said, "Ah, we want to stay together, so let's just go to Harvard."

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: You'll settle for that, somewhere in the middle.

THOMAS POGGE: Settle for that. We went as visiting students just for a year. Then we were overwhelmed by how good it was. It was really good. I was in the philosophy department, where I knew very little about philosophy, and people like Rawls and Quine and Putnam and Nozick and all these people were running around. I learned pretty quickly that they were all famous, really famous.

So I just said, "Well, why don't I stay here?"

So I went to the director of graduate studies and said, "Sign me up. I'm willing to stay here for the Ph.D."

He looked me up and down and said, "Do you know we admit five people a year, and normally people we don't know. Once we know somebody and we know they're not Kant"—that's literally what he said—"we normally don't admit them."

So I said, "Well, we'll see about that. How many courses do graduate students normally take?"

He said, "Three."

I said, "Okay, I'll take six. Let's see what happens."

For two weeks, I was sweating. Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, Frager, Russell, Wittgenstein, mathematical logic, and so on and so forth, all at once. It was the worst semester of my life, let's put it that way. Pretty hard.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: But you stuck with all six?

THOMAS POGGE: Yes, I did. In the end—it must have been a bad year for other applicants or something, but they somehow—

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: You're being too modest.

THOMAS POGGE: Well, Quine kind of liked me.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: So did Rawls, obviously.

THOMAS POGGE: No. He was on leave. I met him once at the mailbox, and that was it.

Quine thought that I had some intelligence and logic or something.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: So what was it like to study under John Rawls? He was ultimately your advisor.

THOMAS POGGE: He was my advisor, yes. Rawls was a very strange personality. He was very, very shy. People at Harvard are pompous for the most part. They're important people. They know a lot and so on. They talk very fast and try to be very, very smart—to outsmart other people.

Rawls was the exact opposite. You would think that he was just visiting or something. He was speaking slowly. He had a stammer all his life, and especially at the beginning when you didn't know him well, he would stammer a lot. He was very reluctant to disagree. For me, it was very frustrating. I would bring him a piece of writing that was very critical of his work and say, "Okay, punch me out. Obviously this is wrong, what I'm saying. Tell me why. How would you defend yourself?"

He would say, "Well, this is very thoughtful and very well done. Let me think about it," and so on. He was very, very modest. It was difficult to get into a fight with him. You could have a fight with Nozick any day—it was very easy—but not with Rawls.

Very sweet, very gentle and friendly, and so on. But as an advisor, I needed somebody who would really counterpunch, and I didn't get that from him.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: What attracted you about his ideas in your time there?

THOMAS POGGE: The theory is just incredibly beautiful to read. At first reading, it's boring and forbidding. Then when you go through the theory, really reconstruct it in your own mind, it has a unity and elegance that is just stunning. That was the main thing that attracted me to it. Then I thought, here is a wonderful opportunity to make Americans understand that their foreign policy is too imperialistic and that they should reach out more to the poor people in the world and so on.

All you need to do is take the same fundamental idea, imagine yourself not knowing in which country you were born, whether you are born rich or poor, and think about how you would want the world to be organized, how you would want foreign policy to be conducted, and so on. It's pretty obvious that you would want a much more peaceful, a much fairer world, a fairer world economy, and so forth.

It seemed too obvious for words, but the first to disagree with that was Rawls. He didn't like this idea. He thought that his original position construction couldn't really be applied to the world at large. He had different reasons for why that wasn't good. That was much of what we argued about for those years.

The only success that I had with him was, in the end, that he wrote up his own ideas about it. He wrote up a book called The Law of Peoples, his last major work, in which he said how to do it: If you really were to take my theory and globalize it, this is how it should be done, and not Pogge's way.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: So you could sort of enter into this dialogue with him.

THOMAS POGGE: Yes, many, many hours. Even after I left, we would talk on the phone. Every now and then I would go up and visit him and so on. We would always have long, long arguments about foreign policy. He was a person who was fundamentally focused on the domestic. His heart was in America. He was a patriot in that sense. He said, "I care about justice in America."

The rest is more complicated. The world is not really to be trusted. If we give too much power away, things are not necessarily going to be better. It's good for the United States to play a leading role, to preserve their leadership role, because we are the repository of justice in the world and the kind of "city on the hill" metaphor.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: It seems that these ideas that you are now writing about are rooted in that time that you were having these discussions with Rawls. But your authorship seems to have turned less and less theoretical and more and more practical over the years. What was the impetus to do that, to really focus on the practical application?

THOMAS POGGE: There was a push and a pull, I think. The push again came out of Rawls and the frustration that I felt that Rawls's theory was fundamentally under-specified. He was thinking of himself as a philosopher who would lay out the general principles and he would then turn it over to economists and lawyers and various other people—technicians—who would apply it. That seemed to me to be fundamentally misguided and naïve, because it seemed that the transmission, bringing the two together, was not sufficiently clarified for other people then to take over.

The defining moment, I think, was 1979 or so, when I had a conversation with him. I went to him and I said, "How do we know whether the first principle is satisfied in the United States?"

My concern in particular was, to what extent do the basic liberties have to be secure? How secure do they have to be? If there's a lot of crime, for example, in black neighborhoods or a lot of crimes against women and so on, can one then say that physical integrity is secure, that the first principle is satisfied?

His initial answer was to say, "You have to ask economists and lawyers and specialists the technical questions. Not of interest to me."

Then I said, "But how are they going to answer the questions? It's your theory. You have to give them some sort of guidance about how they can apply your principle. Otherwise, the principle doesn't really have any meaning. What does it mean?"

If you know a little bit about Rawls, it's a very, very important question, because if the first principle isn't satisfied, social resources have to be devoted to satisfying it. Forget about the second principle for the moment. If it is satisfied, then we can focus social resources on satisfying the second.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: I want to move on to a new topic, but just for those who aren't familiar, could you summarize the first and second principles?

THOMAS POGGE: The first principle just says that everybody is entitled to a scheme of basic equal liberties, and these basic equal liberties have to be secure. Here the question is, what does security mean?

The second principle mainly says that social and economic inequalities should be arranged in such a way that the people in the lowest socioeconomic position are as well-off as possible. So inequalities are justified only if they benefit, so to speak, the bottom position.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: In your own career, you start applying some of this theory. Why did you start with thinking about global inequality and global poverty as your first?

THOMAS POGGE: Simply because the problems there are the largest. There's torture. There's suppression of political opinions and so on and so forth. But in terms of sheer quantity, how many people suffer, how many people are excluded, how many people don't have their human rights fulfilled, this is a vastly larger problem.

Biographically, I could maybe add one sentence. It was a trip through Asia that woke me up from thinking about—that made me alert to that topic. I traveled for four months or so halfway through my graduate career through all of Asia, by trains and buses and hitchhiking and walking and this and that. I just couldn't believe the poverty. I had known theoretically that people are poor in India and so on, but what that meant, how poor they are, was just beyond my imagination.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: So when you write about global poverty—there are many who write about global poverty and say we have a duty—and we have had many people who come here and say that we have a duty to give to the poor, give to the World Bank or whatever organization we choose to help with global poverty. You take it a couple of steps further. You don't shirk from strong statements.

You have compared citizens who support today's international system to passive Germans during the Nazi era or to those who have acquiesced to slavery in this country.

Why go there? Why say this is a crime?

THOMAS POGGE: Because it's true. It may not be the most politic thing to say. It may not be the best way to motivate people. But I really think it is true.

Again the Nazi period—this awakening that I described in my youth was very fundamental there. Lots of people around me, lots of the adults, if you talked to them, said, "What are you talking about? This is certainly not a minor thing. I know my heart. I never intended ill. I never really hated anybody. I never really—"

I said, "Yet you were part of a big organism that, together, did an enormous amount of damage."

Hitler alone could not have killed all these people, and the few people around him. It was done systematically by all these people, in some way, collaborating. Nobody wanted to be impolite. Nobody wanted to be different from the others, and so, like a herd, they went forward.

That's what we are now doing. It seems totally normal to us. We all feel very morally all right about what we do. We nevertheless uphold an economic system in this world that, totally needlessly, keeps one-quarter of the world's population in abject poverty, where the combined income that they have is just three-quarters of 1 percent of global household income—an incredibly small amount.

The world is now rich enough in aggregate to do away with poverty in a way that we rich guys would barely feel. It's a crime to let it continue. One-third of all deaths in the world are premature from poverty-related causes.

This is not a minor thing. This is just a very, very massive problem or crime against humanity.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: I want to return a little bit to the economic inequality, but talk first about a discrete problem that you have sort of taken on and come up with a solution for, how to think big and subvert the system. Let's talk about the Health Impact Fund. Why did you initially say, "The pharmaceutical system is the one I want to take on"? Why was that the first one where you said, "Okay, this is what I can design a solution for"?

THOMAS POGGE: Again, there are reasons and causes. The cause was, I was invited to spend a year at the NIH [National Institutes of Health]. I thought, this was nice of them to invite me, and so let me do something on health. At that time I knew nothing about health. I couldn't have located an organ in my body or anything like that.

Then I wrote up a few papers. One of them was this idea. I looked at this for five minutes and said, "Wrong. This is not how pharmaceutical R&D [research and development] should be incentivized. You shouldn't have high prices."

These are medicines. These are very urgently needed things. You can crank out pills by the thousands at very, very small cost. The cost of the ingredients is minimal. The cost of putting them together is minimal. Why can't poor people have these medicines? It's insane to sell it at a price that is 100 times the cost of production.

Then I thought, how, then, do you do it? Obviously you don't want to slaughter the cow that gives the milk. So you have to somehow reward R&D—

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: The costs are high because of the innovation.

THOMAS POGGE: Because of the R&D. The first pill costs a fortune. Then the next 5,000 cost nothing at all, or 5 million or 5 billion. That's exactly the problem. It's the subway problem, if you like. The first subway ride costs billions of dollars, and then putting an extra rider on the subway costs nothing at all.

The trick is to think about a way to incentivize it so that it's cheap for the following people: That we rich people incentivize the drug companies to develop new medicines in a way that doesn't exclude the poor, that doesn't require us to arm-twist poor countries into suppressing the generic trade, which is now what's happening.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: So that is, in effect, what the Health Impact Fund would do.

THOMAS POGGE: Precisely, yes.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: So it collects all these donations into a central holding place and then rewards innovation?

THOMAS POGGE: Yes, that's basically the idea. It would be government-sponsored for the most part.

The way we picture it is that there would be a certain pool of money available each year to reward new pharmaceuticals. Pharmaceuticals could be registered by the company for these rewards, and if you register, you get a reward that is proportional to the health impact that you achieve with your medicine. If your drug is responsible for 8 percent of the health impact of all the registered drugs in a given year, you get 8 percent of the reward pool. That repeats for ten years, and at the end of the ten years, you have had your reward and you drop off.

What you have to do in exchange, if you register your drug for the rewards, is sell the drug at cost. You make no money at all, no markup at all, sell it at cost. That is determined, for example, through a competitive bidding process among generic manufacturers. You put it out for tender.

The cheapest manufacturer gets the contract, produces the stuff in large quantities; it's sold everywhere in the world at the cost of production, and the innovator—the people who put in the hard work, the expensive work of research, development, testing—they get paid according to how good the drug is, how much health impact it achieves.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: How do you measure impact?

THOMAS POGGE: You measure it in quality-adjusted life years [QALYs], which is a metric that has been around for about 20 years already.

The quick way to explain it is, think of a human life as 80 inches long and 1 inch tall, a little plank. That's when it's fully healthy. Then it's 80 square inches. Then diseases nibble away at the end, because you don't quite live your 80 years, or they nibble away from the top, because you are sick during certain periods of your life. So an actual life may only be 64 QALYs or 33 QALYs or something like that. What diseases nibble away, drugs can restore or drugs can avert the nibbling away of. So the drugs get rewarded in accordance to the quality-adjusted life-years that they avert being lost.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: You rolled out this idea of the Health Impact Fund in 2007, 2008?

THOMAS POGGE: Yes.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: Have you seen any effect from the global financial crisis on the pickup of this idea?

THOMAS POGGE: It goes in both directions. One direction is that many politicians, when they hear any talk about spending money and so on, say, "Go away. Come back in five years. This is not the time to spend any new money."

But then, if I get a second chance to talk to them, I say, "Look, this is actually a much more rational system. The present system isn't just immoral, which is bad enough; it's also deeply irrational because we are wasting so much money."

For example, in litigation, billions of dollars go for litigation between the brand-name companies and generic competitors or brand-name against brand-name. Billions of dollars go for advertising, because if you make a huge markup on your product, then, of course, you try to have more sales, and so you spend billions on advertising. Your competitor also spends billions on advertising. In the end, you are just where you started, except that billions have been spent.

So the existing system is extremely irrational. We could actually save money, for governments, for insurance companies, for taxpayers, if we went to this more rational system of the Health Impact Fund. That's why it's such an attractive idea, because the interests of the poor can be tied together with the interests of the rest of us. Most of the money that we pay for drugs, in the end, ends up in lawyers' pockets, advertisers' pockets, and so on, not in new research, not in safer products.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: You're talking about a system in which billions and billions of dollars are lost. That can also be applied to something else you have spoken out loudly on, which is regulatory capture of businesses giving huge campaign donations and spending a lot on lobbying of the government, which you were talking about before Occupy Wall Street. Tell me more about that and your thoughts on regulatory capture and what we can do to move in the other direction.

THOMAS POGGE: Regulatory capture is a pretty old concept. Mancur Olson is involved in it and so on. We are very familiar with this phenomenon in the United States.

We all know that companies have lobbyists in Washington. These lobbyists are paid by the company to achieve certain legislative outcomes, and companies invest in lobbying because they get more money back. A very simple process: You spend a few million dollars and you get a few billion dollars back from public monies.

What hasn't been studied as much is lobbying one level higher up, at the supranational level. There, the lobbying is much more effective still. Here in the United States there's a counterweight. There's democracy. People vote. If you give too much to banks and corporations and so on, then sooner or later people will be fed up and will vote for another party or vote for different people and eventually put a stop to it. But at the international level, there's very little transparency. There's no democracy. It is a field day for lobbying, essentially.

The way you lobby is by going through the largest, most powerful governments. You lobby the American government, the European governments, the Japanese government, and so on—everybody in the G20, essentially. You try to lobby them for certain outcomes, certain treaties, certain agreements that are to be made at the international level. These things are essentially for sale.

What's particularly hospitable there to lobbying efforts is the fact that these negotiations take place behind closed doors. It's very difficult to figure out what's being negotiated. It's very difficult even after the fact. You can then see the treaty text, of course, but you still don't know who lobbied for certain language in the text and so on, how certain things got in there.

So behind this mantle of anonymity, governments can push things forward and can please their constituency. So just as in the domestic case—in exchange for campaign contributions and so on, parties and politicians are willing to do all sorts of things domestically—they are certainly willing to do things internationally as well.

So we end up with an incoherent quilt of rules and regulations at the international level that benefits various privileged, powerful parties—multinational corporations, banks, industry associations, and so on—but is, on the one hand, dysfunctional and incoherent (see global financial crisis) and, on the other hand, causes a spiral of ever-increasing inequality, which, of course, then strengthens the capacity of the more privileged agents in the next round to lobby even harder for the outcomes that they want.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: We're in a time when a lot of people are talking about these issues. It's in the public discourse, here in the United States, about morality, values, a loss of values in our own political system. Do you find that that conversation is too limited to domestic issues and isn't considering these global issues that you are bringing up enough?

THOMAS POGGE: Yes, absolutely right. I'm very grateful that it's there now. For many, many years, I have always laughed about the United States and said, "These people don't even know how inequality is increasing by leaps and bounds in the United States." There was this total disconnect. In economics departments, people would talk about the Kuznets curve, about how inequality went up to 1928 and went down afterwards. But since 1978, it has been rising, and it's now where it was in 1928.

Virtually nobody knew about the development of inequality in the United States. Nobody in the United States knew.

That's now widely known. Everybody cites the figures. Everybody knows that inequality has been increasing. Everybody knows that it has been increasing especially at the very top, the top 0.01 percent of the U.S. population. They have increased by a factor of 7 their share of national household income and so on.

But the global dimension is ignored. It's an incredibly important dimension. The strongest players in the United States are now lobbying, not so much for domestic things, but they are lobbying for international things. It's kind of forum-shopping. What you now do is, you try to get rules and regulations adopted at the supranational level that benefit you, not only in the domestic theater, but internationally. So a great deal of the problem, the undermining of our democratic rights, occurs at the international level, and no longer just at the domestic level.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: I want to take some questions, but I don't want to end on such a scary note. So I'm going to ask you another question. Sorry to be a little leading. Do you see areas of hope? Are you optimistic that maybe out of this domestic conversation can rise a global one?

THOMAS POGGE: Yes. I think there are two different sources of hope here.

One is what I already mentioned, the education. Many of us learned the hard way that there is a problem in our system, a systemic problem, and that we have to sort of think more intelligently, more systemically about what the sources of that problem are. That's one thing.

The other thing is a more subtle hope, but maybe even a stronger reason to hope. The global financial crisis wasn't even so good for a lot of the big players. So what you get here is a kind of prisoner's dilemma.

You have some players that are strong enough to lobby, strong enough to buy themselves a little slice of the rule-pudding. The car companies have certain interests, and so they combine, they lobby, and they get a certain result. The banks have certain interests, the IP [intellectual property]-heavy corporations and so on, the drug companies. Everybody buys themselves a little bit of the rule-pudding at the international level and sometimes at the domestic level.

The outcome of that is incoherence in the rule system. The rules are often ill-fitting. What people have learned, I think—even very powerful agents have learned—is that they have more to fear from the power of other very powerful agents to buy themselves pieces of the rules than they have to gain from their own power.

So the prisoner's dilemma situation is that maybe they would all be better off if all of them had less power. Of course, the best would be if only I have power and nobody else. But that cannot be had. So the second-best is if we all have a little bit less power, we very powerful, very privileged agents, and the rules are shaped in a somewhat more coherent way, serving common purposes, defined through a somewhat democratic process.

That's if they were intelligent enough to understand it and—here comes the other important point—if they were more long-term. That's one big danger that corporations—I was supposed to end on a positive note.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: No, no, no. I'm feeling better now. I'm feeling better. So you can continue.

THOMAS POGGE: The problem is that corporations have long-term interests, but the people running them often don't. A huge problem. So the people running them don't see this long-term prisoner's dilemma situation as a real problem. They say, "Well, the crisis is not going to happen in the next six years. Let me just cash out on my bonuses and my stock options and so on and so forth, and if my company then goes down the tubes in 5 or 10 or 15 years, that's all right."

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: Great. You have sparked a lot of ideas, and I'm sure we're going to have some great questions from the audience. Now I throw it open to you. What do you all have to ask our practical philosopher here?

Questions and AnswersQUESTION: Edith Everett.

You started out by speaking about the lack of awareness of the global poverty, talking about the individual. I want to ask you, as a person who wants to be an ethical individual, how do we separate wants, needs, and responsibilities in some kind of balance so that we can live with ourselves?

THOMAS POGGE: I think the best start in terms of needs is to look at the kind of minimum floor that is defined in the human-rights documents. I think the human rights documents are the most authoritative, most culturally invariant, shareable set of documents that we have on that. We have a Covenant on Social, Economic, and Cultural Rights, which lays down in some detail what the minimum requirements of human beings are.

You might say that they rise, to some extent, with the progress of history. But the documents are pretty scanty in terms of what they provide for basic nutrition, clothing, clean water, basic medical care, basic education, and so on.

So this would be a floor that is culturally pretty invariant and that we, at the present level of economic development, are certainly very, very easily able to provide to everybody in the world. We should just try to design our economic systems in such a way that everybody has that.

With regard to wants, I think our responsibilities are much less. If people have certain unfulfilled wants, they could range all the way to a ride to the moon or having various kinds of luxuries and so on. There the moral urgency is much less.

Of course, we want a world in which there is a minimum level of equality, in which the inequalities are not enormously large. But again, I think, in the stage where we're at, where still 2 billion people live in abject poverty, we should focus on these needs first and foremost. Our primary responsibility is to make our global economic institutions human rights-compliant, to design them so that they fulfill human rights insofar as possible.

QUESTIONER: [Not at microphone] … to the individual. How do you know where you should stop supplying your needs and wants, and give to the other, who is needier than you? How do you find that…

THOMAS POGGE: That's a difficult question. I think the very minimum that we should all do is, we should do our fair share to protect needy people in the world. Take a back-of-the-envelope calculation.

If you say there are 2 billion very poor people out there and maybe 1 billion affluent people living in the rich countries, or maybe even half a billion, then there are four of them for every one of us. But we are so much richer—300, 400 times richer—in terms of our income that, at very little sacrifice, a few percent of our income, we can double, treble, quadruple the incomes of these very poor people. Here the greater value of currency also helps.

So at the very least, that's what we should do.

Even if we do that and do enough to get four people out of poverty, there would still be many, many others left, of course, because not every one of us is inclined to do what we ought minimally to do. Then the question is, how much more should we do? How much more are we required to pick up the slack left by others who are doing nothing? That I don't have a very precise answer to. I personally try to do a good bit more. But I think that the very minimum that each of us absolutely has to do is that sort of fair share.

QUESTION: My question relates to the Health Impact Fund. I found it very interesting how you outlined the peculiarities of the pharmaceutical industry and the situation of health worldwide. I was wondering whether you can think of any other industry in which an idea such as the Health Impact Fund could also work or could also apply.

THOMAS POGGE: There are two other industries, two other branches, where this could work.

One is with ecology, with all the modern inventions that are green, clean inventions that make our ordinary productive processe—power plants and so on—less harmful to the environment. Here again, it's deeply, deeply irrational that somebody who invents a wonderful new way of reducing emissions is rewarded with the power to mark up the price of the invention so that it is underutilized, so that people don't use it because it's too expensive.

In many developing countries today, people who build a new power plant have to decide to do it under the old, let's say, Soviet-style technology, which is free and available for everyone, or to use the latest technology, green, clean technology, and put that in, but then you have to pay licensing fees to the inventors. That's foolish for all of us, because we all breathe that air. We all suffer, and our next generation and so on will also suffer.

Again, the same system would work: Tell innovators of green, clean technologies, "If you license that for free, let the world use it for free, we will pay you on the basis of emissions averted."

Another area is agriculture. There are all sorts of new plant varieties that have been developed that make do with less pesticide, less fertilizer, have lower emissions, and so on. Once again, the way in which we reward these innovations is in terms of allowing the innovators to mark up the price. Same problem, same solution. Pay the innovator, in exchange for licensing these things for free, on the basis of nutrient yields increased, pesticide use reduced, fertilizer use reduced, and so on.

These are two areas where it would work.

QUESTION: Sondra Stein.

What do you do in situations where the international community wants to bring aid, but the violence in the country, the different groups, or a dictator sabotages and makes it not possible to bring adequate food and health care? What is the international responsibility there?

THOMAS POGGE: I would say, given how much of a gap there now is, we should focus attention elsewhere. It sounds cruel, but I think that's the only way to go. We have a tendency to do the exact opposite. If there's a hotspot with a little civil war and so on, it's in the news, and then the NGOs [non-governmental organizations] say, "Oh, let's be there. Let's have our logo there. Let's have our flag there so that people in the evening news can see that we are there; we are doing something."

That's the wrong reaction. The right reaction would be to say, "Let's go to an area where there isn't a political problem." All of India is available. It's politically pretty easy to operate in India, for example, and many other countries where there is a lot of poverty and where you can operate much more effectively, where your trucks are not hijacked by some guerilla group and then sold for weapons and so on, where you are much more effective in the aid that you deliver. Go there. Do it over there and forget, for the time being, these areas.

We don't have enough money anyway right now to operate in all the areas that need our help, so let's operate where we can be effective and let's not feed wars and civil wars and so on where we, in any case, can't operate very effectively.

QUESTION: Tom Wynn [phonetic].

My question is about your movement from theory to application and practice. Do you feel that you have had to make any compromises in either logic or the framing of your logic as you are trying to implement some of your policies?

I'm sure you have heard the criticism before, "Oh, it looks great on paper, but I'm not quite sure how it's going to work in practice." As someone who has been at the State Department and has sat in on some of these secret meetings, like ACTA, the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement, I can easily imagine them saying, "Who's this guy telling us that we're killing people?"

Any compromises that you feel?

THOMAS POGGE: It's obvious that I will not convey all parts of my message to all people at all times. I couldn't. Obviously you adjust to the person you are talking to.

If I go to the State Department or I talk to politicians in India or in Brazil or whatever, obviously I will try to take account of the situation and try to package the message in a way that they may find appealing, throwing in some of their own self-interest, the ways in which it might make them look good, and so forth.

I don't see that as necessarily a compromise in any kind of big way, because I don't think that I have an obligation to give people everything that I think about a certain topic. It's okay to package a little bit, to add a few things, to subtract a few things, and so on. That's maybe not quite compromise.

But where I do compromise is, of course, in designing something like the Health Impact Fund. If I said, in typical philosopher's fashion, "Nice try. No cigar. Let me tell you how pharmaceutical innovation should be—how the whole system should be revamped," I would get absolutely nowhere.

I have to deal with existing pharmaceutical companies, who are just a little bit larger than I am in terms of the money they have available to spend on lobbying and advertising and so on and so forth. I have to deal with the powers that be, and if I don't manage to make the Health Impact Fund compatible with what the interests of the pharmaceutical companies are, then the Health Impact Fund will never go anywhere.

So it has to be attractive. There has to be something in it for the pharmaceutical companies. They have to see a reason to allow this thing to go forward. That's where you have to compromise, maybe in the hopes of, in the long run, getting to a fully rational system. But in the medium term, you have to design the system in a way that will generate sufficient support to get it adopted.

QUESTION: George Paik.

I'm picking up two aspects of this discussion, one having to do with systemic arrangements, if you will, one having to do with results and outputs in terms of poverty distribution and so forth. I'm trying to think of a case that would get at the two of them. The best I can do at the moment is the following.

If you take some of these free-trade people, if you will, at the World Trade Organization [WTO]—obviously the World Trade Organization is organized around nation-states, many of which are part of the system, I think, that you would describe as being problematic. A lot of them, in all sincerity, from what I have made out, will say something along the lines that this organization is meant to do things like undo agriculture subsidies of the Europeans and the Americans.

In fact, if progress on some of those were to happen, there would be considerable amelioration. For instance, there are a number of countries which would go far towards being better off if cotton subsidies were lifted in the United States and Europe.

How do you view the tension—I'm sorry, that's not the best example, and "tension" may not be the right word—the relationship of the systemic to the result? Is it fine for these folks to be pushing the lifting of subsidies within WTO? Is there working within the WTO or some like structure a precedent problem? Do you have a view on that, a systematic view on how that plays out? Does that make sense?

THOMAS POGGE: I hope so. You can come back if I don't capture the question quite correctly.

The first thing to say, I think, is that ultimately what matters is results. We want to design systems in such a way that we get the results that we want. Which results we want is a very difficult question, which has strong moral aspects.

There was a time, the 1980s, and 1990s, and the early parts of this millennium, when we all thought that these were purely technical questions, and let the economists worry about what the right results are. We now know better, I think. We know that the results have to be specified. It's a value question. We need to engage citizens, even philosophers sometimes, to think about what the morally appropriate results are.

Here again, I think the best basis that we have is what I said in response to the very first question, our agreement on human rights. We want first and foremost a world in which human rights are fulfilled, as far as that is reasonably possible. So we want to adjust our systems, both national and supranational, in such a way that we get that result.

You bring in the WTO. We now have systems that are not designed to achieve that result. In many ways, the systems are designed by a very small minority, those people who have the power to lobby, the power to influence the rulemaking processes, at the expense often of large majorities of human beings. If we want to make change and want to make the results of the existing systems better, we have to work within these existing systems and call for reform.

Your example is a good example, where you can appeal to the libertarian rhetoric and you can say, "Look, by your own standards of free and fair trade and so on, these subsidies are violating the very principles in the name of which you have pushed the WTO forward—namely, this theory of comparative advantage, that poor countries would be able to enrich themselves by being able to compete on even terms with producers in the rich countries and so on. You are undermining your own rhetoric, your own justification for free trade by maintaining these grandfathering rules with regard to the subsidies."

So within the organization you fight against the subsidies, with the arguments that you gave—that they violate fair trade or free trade and that they also are keeping millions and millions of people in poverty, who would be much better off if they could sell their cotton on world markets—and try to shift the system in that way.

QUESTIONER: If I could quickly follow up, do you feel that a lot of these—how prevalent do you feel many of these institutions that are operating unfairly have within themselves the seeds of their own rhetoric that could be a basis for reform? Or is there some basis for judgment that you would proffer?

THOMAS POGGE: I think it's not sort of the main case. It's an exception. Here's an exception where, even by the ruling ideology, if you like, of free markets, we are falling short, and falling short in a way that is clearly implicated in the great harms that the present system does to the poor.

But it's also true that if we corrected those shortfalls that are internal to the ideology, as I called it—even if we corrected them, massive poverty would persist. So we also need a fundamental shift in values, where we say that free markets are not an end in themselves, but rather markets are there to serve people, and we have to judge them by that standard: How well do they do by the standard of meeting the needs of people?

Every market is, in a sense, designed and constrained and shaped in certain ways. Here we have to use our degrees of freedom—how to shape, how to design markets—in such a way that we get the result that we want.

QUESTION: I want to comment on the harsh statement you made at the opening of your remarks, stating that most of the world that really does not pay attention or that sees what's going on and does nothing about it is like Nazi Germany watching the horrific atrocities and doing nothing about it. Then you went on to describe yourself, as a younger man, who, before you traveled, intellectually knew what was happening. But until you actually had the visceral and emotional impact of seeing it, you were not able to have the kind of empathy that's required to make changes in the world.

I would suggest that most of the people are at the first stage you were at before you traveled in Asia for those four months.

What can we do about that? Have you thought about some sort of massive kind of education process that could be enacted in order to make these changes? It seems to me that without the citizenry having the understanding that you developed—and, after all, governments are composed of people, and many of these people do not have the same depth of understanding that you developed—it seems to me we will not have these superb changes that you are recommending. Have you thought about preceding these efforts with some kind of education process?

THOMAS POGGE: Yes, I've definitely thought about it, but I didn't get very far with it. I think what you are raising is extremely important. It's completely right.

Let me say also, again as a German, that this was also the problem with the Germans. The world felt normal to them. They were indignant often when I needled them on their role in the Second World War—where were you, and what did you do, and so on? People were saying, "Look, I know that I did nothing wrong. I know. I was there. I was not confronted with—yes, it's true, there were fewer Jews around, but we didn't really know what was happening."

The world felt normal, just like it feels normal now to most adults here. That sense of normalcy we have to break somehow. That's your point.

This would have been a horrendously difficult task in Nazi Germany, of course, where the political pressure, with the Gestapo and so on, was very difficult to mobilize. But here we have freedom of speech and freedom of opinion, and we can do a lot of educational things. But it's very remarkable, to me anyway, that there's so little art, so little literature and cinema and so on, that really is looking at this problem head-on. One-third of all human beings die from poverty-related causes, and nobody makes a movie about it?

There is A Tale of Two Cities. There is Toni Morrison, one of my favorite authors, who really, in very vivid language, is describing things and awakening us to a problem. When I came to this country, I knew very little about race relations. I read a few novels by Toni Morrison, and I was very deeply moved and I very deeply understood at least some aspects of what it's like to be black in America.

That's what we need. We need somebody to—it couldn't be me. I'm a dry philosopher. I can't write literature. I can't make movies. But if there were people who could take that on, I think it would make a world of difference. One good movie, one good novel could do more in that area of motivation than 15 books by someone like me.

QUESTIONER: You speak about lobbying on the supranational level. Perhaps there should be an effort to lobby on the intellectual level to intellectuals and creative people to participate in this kind of education, so you could achieve these goals.

THOMAS POGGE: And ordinary citizens.

QUESTION: Ron Berenbeim.

The touchstone of much of what you said is human rights. The best formulation I know of with respect to human rights is the UN's Universal Declaration. The problem, as I see it—because that embodied a compromise between essentially political rights and economic rights. As I recall from the historical debate that took place, the Soviets were very strong on economic rights and the Americans were very strong on political rights. So they just decided to have them both.

When you have a formulation of that sort, you have an inevitable conflict between rights, or potential conflict. For example, you have in the Universal Declaration a right to education, but you also have a right to subsistence. In many countries, if children don't work, the family has no subsistence. On the other hand, if they are not educated, they are losing one of their basic rights. The country in the long run will suffer and not have the kind of civil society where the sorts of questions that the last commenter mentioned are being discussed.

How do you prioritize between rights in your scheme? Or do you find a way out of that problem?

THOMAS POGGE: Let me say first one little sort of amendment to your historical description. In the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, I think the socioeconomic rights were also grounded to some extent in the American thinking. There was the famous "Four Freedoms" speech by Roosevelt. Of course, Eleanor Roosevelt's role is also very important in that context. I don't think it's quite right to say that we have the Soviet Union to thank for what human rights there are in the socioeconomic.

I do think that there is really common ground here. We all want an economic system that works, and works not just for some, but works for all. That gets me to the main point: namely, I think we are beyond the point of scarcity, where we have to make these decisions.

It's true that there is very substantial scarcity of the sort you describe in many poor countries, where you have to make hard decisions. Is the child going to work in the fields, and are we going to have enough to eat, or are we going to send the kid to school and then we just eat less and maybe risk permanent damage to the brain development of the child and other children, and so on?

This sort of scarcity is local scarcity. In the larger scheme of things, globally speaking, we can very easily eradicate that.

So what I would say is that we have to make a concerted effort, spend more money, and, more importantly, spend it more efficiently, to ensure, on the part of the rich countries, that economic opportunities in the poor countries are there. Nobody should have these kinds of problems.

Just to again remind you of one number that I mentioned earlier, the bottom quarter of the world's population has three-quarters of 1 percent of global household income. If you doubled that, that would be another three-quarters of 1 percent. We could easily divert that money, double all the incomes in the bottom quarter, and hardly ever feel it.

So I don't think we have to at this stage compromise. Of course, it can't be done with national resources alone in many cases. But with international resources, it can be done very, very easily.

QUESTION: My name is Blaine Fogg.

Your Health Impact Fund, I take it, you said, would be a government-sponsored fund. Presumably, some bureau or somebody would decide who gets rewarded and how much. Haven't you just nationalized the pharmaceutical industry, number one?

Number two, drug discovery is like drilling for oil. For every gusher, there are I don't know how many dry wells—10, 20, 30, 40, you name it. Who compensates people for drilling the dry wells on their way to try to find a gusher? If you don't have any Lipitors, blockbuster drugs, under your scheme, haven't you removed a lot of incentive for people to spend millions and millions of dollars to develop drugs that are going to be efficacious?

THOMAS POGGE: Let me take them in opposite order. The risk is obviously there. The risk will be covered in exactly the same way as it's covered now—namely, the drugs that pan out, that get marketing approval, will pull along the failed endeavors. They get overpaid, basically. How will that happen? Basically, you have demand and supply of innovation. The Health Impact Fund has constant pools. Let's say $6 billion per annum.

If pharmaceutical companies think that registration is a good deal, if the reward rate is high enough, they will register their products and they will do further research. Conversely, if they think that the rate is poor, they will do less research. So the price of innovation on the Health Impact Fund will always equilibrate to a level that the pharmaceutical companies will find lucrative enough. It's a kind of built-in guarantee.

We don't know how many drugs we will have registered at any given time. We think it will be about 25 or so, if we have the $6 billion figure. Twenty-five drugs—that means two to three drugs will come on every year; two to three drugs will drop off after their ten-year reward period is expired.

But if we are wrong about that, if that's not lucrative for pharmaceutical companies, why, then, we get fewer drugs. It's certainly true that if it's only one drug in the fund, that drug would make $60 billion over ten years, and that vastly beats even Lipitor, with its $13 billion a year.

The money will not stay on the table. How many pharmaceutical companies will come forward is anybody's guess.

The second thing is, are we nationalizing the pharmaceutical industry? No. Nationalizing would mean that we let things like the NIH or universities take over and let them do the research. I don't want to do that. I think that companies are far better able to solve the very, very complicated problem of getting drugs from conception, from the workbench, all the way to the end user and making them effective for the end user.

It's a very complicated problem, where all the different parts have to be adjusted to one another. That's precisely what companies are very good at doing—a problem like delivering parcels solved by UPS or delivering ice-cold Coca-Cola all over the world, in the right quantities to the right places. I don't want any government solving a problem like that, because they aren't going to do a good job.

What government does here is just incentivize it. Government just says, "We pay you for results." That's a little bit similar to how the Defense Department operates—or, ideally, should operate. You get me a plane that works or you get me a gadget that works, and we will pay you on the basis of how well it works. Different companies can compete and so on and so forth.

JULIA TAYLOR KENNEDY: In the past hour we have covered a huge amount of territory, which I think is actually an apt reflection of your intellectual life. Thank you so much for going there with us.