"The Red Hand of Ulster" was originally published in WORLDVIEW Magazine (1958-1985), a publication which featured articles by political philosophers, churchmen, statesmen, and writers from across the political spectrum.

Patricia Moir traveled through Ireland in 1975 under the auspices of the Chinook Learning Community. Moir spent the summer living in a Protestant housing estate in Belfast, where she organized a recreation program for the children. Her account of that summer shows a vicious cycle of everyday brutalization and bigotry, handed down from generation to generation.

Download the original article below.

An old Irish legend tells of a boat race where the prize was the kingdom of Ulster and the victor was the first to "touch the shore."

O'Neill, seeing his boat slip behind, cut off his hand, flung it ashore, and won the kingdom. Ulster, but for three counties, is now Northern Ireland. O'Neill's bloody hand has been preserved through the ages as the Red Hand of Ulster, seen on flags, postage stamps, pendants, and paramilitary banners. The passions that led O'Neill to bleed for Ulster have survived as well.

When I arrived in Belfast in late June, the Red Hand was waving from Protestant doorways to herald the impending Orange Parades. On the 12th of July, Orangemen and many Protestant followers would take to the streets to celebrate the Battle of the Boyne, where William III of Orange (a Protestant) defeated James II (a Catholic) to take control of Ireland. For weeks in advance huge banners arched the streets, exhorting everyone to "Remember 1690." Indeed, the people spoke of "King Billy" with such familiarity that it was easy to forget the battle occurred almost three hundred years ago.

At Cranston Estate, the Protestant housing project where I was living, preparations began early. (The name of the estate has been changed, as have the residents' names.) Union Jacks and Red Hands were hoisted above doorways; banners of red, white, and blue were stretched from house to house; and the mountain of refuse continued to grow in a vacant lot, awaiting that midnight match that, on the eve of the 12th, would transform it from a pile of junk into a blazing bonfire. The whole estate was poised for the transformation, or at least the drama of the fire and the pomp of the parades. As it was, Cranston appeared to be dying—at once the victim of apathy and violence. Fresh white houses with brightly painted shutters and well-tended rose gardens were competing with graying, graffiti-trimmed bungalows—and losing. The streets were paved in broken glass, testimony to the popularity of bottle-smashing. Unemployment was high at Cranston and boredom kept pace. The latter, mixed with alcohol, was a combustible that brought Scotts and Hardwicks to blows in the street and left a man beaten and bloody in the gutter for not paying his fifty pence to enter the monthly dance.

I was on Cranston Estate at the behest of Belfast's Voluntary Service Bureau to organize a summer recreation program for the children. I lived with the Douglases, who had moved to Cranston thirty years ago, when it was new, and had raised nine children there. Like many of the original residents they traced the decline of the estate to the tensions of the sectarian "troubles" and to the arrival of a "different class of people."

Ten or twelve of Cranston's eighty families drank heavily, fought readily, and almost eagerly stirred up trouble on the estate. Their children, like children everywhere, followed their parents' lead. They commanded attention by hosing down a dressing room at the public baths, by smashing windows in the community center, by setting fire to vacant bungalows, by flinging a visitor's ivory bracelet into the murky boating pond of a neighborhood park. I arrived on the estate forewarned by the Voluntary Service Bureau that the children were "high spirited." A report from volunteers of the previous summer suggested what a remarkable understatement that was; on an evening field trip some Cranston teenagers had burned and slashed the inside of an Ulsterbus. A year later this was still a major topic of conversation on the estate, the Tenants' Organization having exhausted its funds (raised at monthly dances and weekly bingo games) to compensate the bus company to the tune of several hundred pounds.

At least fifty children came to a converted bungalow that was the community center: toddlers for babysitting, grade schoolers vying to go on field trips, teenagers because there was nothing better to do, and hooligans to fling paint, smash windows, and impress each other with their toughness. The latter group spanned all ages. While even the hardest and most destructive among them could be touchingly eager to please—almost honored to run errands—they were just as likely to set fire to everyone's artwork or throw paint on the new projector. They were, like Cathy Clarke, an erratic mixture of deference and defiance. Cathy would follow me everywhere, holding my hand, grinning up at me through blonde bangs and a dirty face and asking, "Squeeze my hand tighter, okay?" It was difficult to connect this sunny Cathy with the one who kicked our bus driver, broke into houses on the estate, and ran away from a group outing to be brought home six hours later in a police car. At eight she was still cuddly and tractable. But what, I often wondered, would she be like in five years, or even one?

My reverie would be rudely broken when it came time to clear the pool. There were always stragglers who refused to leave the water. To approach the edge of the pool was to invite being pulled in fully clothed. To go in swimming was to risk having your bathing suit pulled off. Several men, employees of the baths, would aid in the exhausting task. Invariably one of the kids would spit at them, shout an obscenity, and we would be told not to return, at least not with "that one." Another outing was disrupted when some of the kids enraged a park warden by gouging holes in a four hundred-year-old thatched cottage and pulling up newly planted shrubbery.

In the immediacy of the chaos it was difficult to sort through motives, difficult to forget whose father was a leader in the paramilitary organization, and almost impossible to believe in the proffered solutions. "You need to capture their imaginations," advised a drama group that traveled among the Belfast estates. "We need to spend time in the street just relating to them," announced Ian, my eighteen-year-old co-worker from England, who bought the kids cigarettes (even nine year olds would beg, "Give us up for a fag'") and bought their parents drinks. "They need discipline," insisted Mrs. Douglas. "You're too soft with them." She thought the children had changed with "the troubles." "They see their fathers and older brothers carrying guns into the house and talking tough."

The boys in particular seemed to admire the paramilitary Ulster Defense Association, many of whose members, at seventeen and eighteen, were hardly more than boys themselves. The Cranston UDA commander, "Big Arlee," rivaled the Protestant hero, "King Billy," as a subject for the childrens' paintings. Young boys would linger in the doorway of the UDA hut to watch Big Arlee and his heavily tattooed cohorts shoot snooker. At Cranston the UDA elicited admiration, ambivalence and outright fear. The Douglas's neighbor received some late-night callers who left him badly cut and beaten. Reasons for the attack were rumored about the estate, ranging from "he owed money" to "the commander wanted his house." A few days later Big Arlee appeared with his face battered black and blue and his eyes swollen shut. The story was that he had been "reprimanded" by his superiors in the organization.

"I'm not saying we won't need them someday," Mr. Douglas remarked, "but now they're acting as bad as the other side." (Catholics were often referred to as "the other side" or "the other sort," although some people used the cruder terms, "taig" and "fenian.")

The best way to live on the estate, it seemed, was as anonymously as possible; certainly, many people had lost their voices. But it wouldn't always be that way, predicted a friend whose brother had been shot by the UDA and was living in exile in Scotland. "When these troubles are over, people will be lining up to give Big Arlee a thumping."

Subscribe to the Carnegie Ethics Newsletter for more on ethics and international affairs

Ian and I first arrived at Cranston on a Sunday evening, not knowing any of the children but aware that a "minibus" would take us and a dozen of them to the beach the following morning.

Pressed for time, we wrote down the names of the first twelve children we met on the street and contacted their parents for permission. Monday morning our list was not to be found, and we stood in front of the center trying desperately to remember names, or at least faces, while thirty kids pushed and clutched at us, screaming: "You promised me, you promised me." Several mothers got into the act, one insisting that we take her son because he was feeling ill. Five or six dogs chased a ring around the chaos, now and then converging into a fighting, snarling knot. A hastily organized game ended with equal dispatch when the ball ruptured on street glass.

When the bus finally arrived, an hour and a half late, fifteen kids piled on, three more than there were seats for or the bus was insured to carry. The "chosen fifteen" let loose with a deafening cheer as we careened out of the estate, waving to those left behind. Very soon we had traded the narrow, crowded streets of Belfast for the green and graceful countryside, where cows grazed near the doors of pebble-dash cottages and ivy crawled up the sides of old granite houses.

Like most children on field trips the kids belted out the tunes of the times. Even seven year olds sang about "shooting every bastard in the IRA." Some of the boys knew cruder songs: "I'm going to sit the Popey on the table and ram the poker up his hole." There followed an ironic rendition of "Last night I had the strangest dream I ever dreamt before, I dreamt that all the world agreed to put an end to war."

"Where," asked the driver in surprise, "did you learn that?"

"In school" they chorused.

Several times traffic on the tarmac highway came to a complete and patient halt as a herd of cows lumbered across the road, some of the big animals brushing right against the minibus. The children whooped and screamed and reached out to touch the cows. When we finally arrived in the seacoast town of Newcastle, the beach was crowded with families on holiday: children toting sand buckets, young couples strolling hand in hand along the promenade that curved around the bay. Old men in tweed coats and caps sat on stone benches, staring out across the sea, perhaps to catch sight of a returning carrier pigeon. Behind the seawalk, amidst the sweetshops and the three-story pastel houses, stood the bombed and blackened skeletons of the cinema and a municipal building.

The kids spent the afternoon alternately dashing in and out of the sweetshops and the icy Irish Sea. I brushed sand from wet bodies, beachcombed for missing socks, and admired Cathy Clarke's fistful of rocks and shells. As we hunted more shells two of the older girls from Cranston approached Cathy, kicked her sharply, struck her across the back, and disappeared into the beach crowd. The Clarkes (Cathy and her younger brothers and sister) were the scapegoats of the estate. Though I never learned why, it was a scene I would see reenacted many times. Children twice their age and several times their number would strike them with impunity, the attacks seemingly sanctioned by the general disdain for the Clarkes. (Shortly after I left Cranston, two sixteen-year-old boys beat Rory Clarke unconscious and locked him in a coal bin.)

As we drove through Belfast on the way back to Cranston the steel and barbed wire barricades stood in grim contrast to the cows and the beach. Signs hung from the barricades. "We regret the inconvenience to the public of searches made necessary by acts of terrorist violence." People were waiting in long lines to go through the turnstiles where their bags would be searched and they would be frisked. Once inside the cordon they would be searched again upon entering a building. In the city center the legacy of violence is everywhere, from British soldiers stationed on street corners, their rifles poised and ready, to the extraordinarily thin slots in letter boxes that will accommodate only the flattest envelopes.

Bomb damage is not easy to pinpoint, since it is often difficult to tell whether broken buildings are the victims of terrorists or of Belfast's large urban renewal program. (Many Belfasters speak resentfully of foreign cameramen who sensationalize the problem by focusing their cameras on the city's demolition efforts.) Though nothing is certain in guerrilla warfare, violence has been most prevalent where Catholic and Protestant areas merge into towering sheets of corrugated metal, ironically dubbed "peace lines."

Though nothing is certain in guerrilla warfare, violence has been most prevalent where Catholic and Protestant areas merge into towering sheets of corrugated metal, ironically dubbed "peace lines."

Cranston Estate, tucked into the heart of a Protestant stronghold, is not a conflagration point; but its families are not strangers to violence.

The Hardwicks, one of the most volatile families at Cranston, told me during my door-to-door campaign to meet the residents that they had "lost two sons to the British Army." The story bandied about the estate portrayed the sons as common criminals, one shot in a robbery, the other run over by a military vehicle when he tried to crash it with a rolling beer barrel. The family, however, lived by their own version. Mrs. Hardwick would stand in the yard, unsteady from pills and drink, screaming that her sons had "served their country."

The army patrolled Cranston regularly. Sometimes twice in one night a jeep would cruise through the estate, the soldiers leaning their rifles against the back window. A few years back a midnight bomb exploded on the edge of the estate, shaking the bungalows to their foundations, knocking all the decorations off the walls, and locking itself solidly in the memories of the people. Most violence, though, was spawned within the estate by the UDA beating up someone or by one family lashing out at another over a slur against one of its members. The family name commanded a loyalty that outstripped facts and fueled a clannishness that led family members to refer to each other as "our John" or "our Mabel"—"our" sounding almost like a title.

Rarely was any conflict on the estate limited to those directly involved. When Mrs. Hardwick summoned Eileen (a farm girl working on the estate) to inquire about her allegedly hitting a young Hardwick, Jane found the entire family plus several neighbors waiting for her in the front garden. The passions that inflamed Cranston—or at least the dozen families who held sway—had more the flash and fizzle of irrationality than the substance of angry conviction. Some of the parents who complained most bitterly and threateningly about favoritism on the field trips would invariably hold their children back when bus seats were actually available. These people seldom ventured farther than the shops at the top of the road. They symbolized a stagnation that was the most tragic aspect of life at Cranston. Most Cranston residents did not remain on the estate, but many did live almost entirely within Protestant, East Belfast, rarely crossing over the River Lagan to the city center or beyond. Fear of alien territory is very real.

As serious as any of Belfast's problems is the jealous, protective feeling many people harbor for their own areas. Magnified to include Protestant Belfast or all of Northern Ireland, this "turf mentality" can, and does, become deadly.

Within the Protestant community it is also divisive. The paramilitary organizations have splintered into several mutually antagonistic groups, much as the Provisional IRA split from the Official IRA. Children at Cranston sustained fighting rivalries with the children of neighboring Protestant estates. A beach outing nearly became a small riot when a boy from a neighboring Protestant estate shoved "our Patrick." Several blows and bottles were thrown before we managed to herd our kids back onto the minibus.

Cranston's physical isolation seemed to heighten a "spirit of seige." Although the people lacked cars, refrigerators, and nice clothing, perhaps their greatest deprivation was not being able to see beyond the graffiti-covered fences that advised them to "f*** the Pope." [spelled out in full in the magazine] Bounded as it was by the fences, trees, and railroad tracks, Cranston was not visible to the surrounding and more affluent neighborhoods. From inside the estate one could see only the Harland and Wolff shipyard cranes towering over the docks and the tiny white specks of sheep on a distant hill.

There was only one telephone among the ninety bungalows, and it was owned by the Nagels. Mr. Nagel ran a grocery bus and was "president" of the impotent ten-member Tenants' Organization that was known to oppose the UDA, though not too vocally. Mrs. Nagel told me that her husband was a Protestant but she was "of the other sort" (a Catholic) and in recent years had been quite nervous living at Cranston. Their summer holidays always took them away from Cranston during the 12th of July Protestant hoopla. After I left the estate Mr. Nagel made some ill-considered remarks about the Cranston UDA, and they retaliated by shooting Mrs. Nagel. She survived, and the family fled to England.

On the 12th of July, that day the Nagels annually avoided, Protestantism and Loyalism (to Northern Ireland and the British Crown) combined to surpass lesser allegiances.

Although I met Protestants who wouldn't dream of going to the Orange Parades or the bonfires, at Cranston the 12th was a great day. "Even better than Christmas," some of the children told me. They were anxious for me to see their big bonfire, or "bonny," as they called it. Lorraine Stone, an agile, creative girl of ten, confided that she and a few of the others would have their own little "bonny" first.

"We've got our own little Pope ready to burn and everything."

"Why do you burn the Pope?" I asked.

"Because we always have."

"But why?"

"Because we hate him." This she said very sunnily.

"Why do you hate him?"

She twisted in her seat on the window ledge, not answering directly. "We've always burned him," she repeated.

"But why do you hate him?" I persisted.

She scrunched her forehead a bit. "I dunno," she said finally. Someone called to her and she skipped away.

She scrunched her forehead a bit. "I dunno," she said finally. Someone called to her and she skipped away.

I did not spend the eve of the 12th at Cranston, but on a larger, newer estate with the Douglases and their family. (They predicted a rowdy night at Cranston; as it turned out, a small boy was hospitalized with burns and a lad of twelve was badly beaten.) With the Douglases I drank, sang, laughed, and was overcome by the tremendous warmth and spirit of these people who welcomed me so totally into their lives and who kept their strong decency though surrounded by prejudice.

From the steps of the house we could see five separate fires on the estate and the red-on-black glow of many in the distance. We approached the biggest fire and could feel the heat on our faces from fifty feet away. Sparks shot through the night like thousands of fireflies, fading before they touched us.

Hundreds of people circled the fire, singing, dancing, and fueling the blaze with sofas, truck tires, whole trees, and refuse collected over many months. I did not see any "Popes" burned in effigy. By morning the fire had burned down to a few sparks, a wisp of smoke, and a large pile of ashes. The estate was nearly deserted as people flocked to the Orange Parades. Orange Lodges from all over Britain and as far away as Canada marched a thirty-mile round trip to a field outside Belfast.

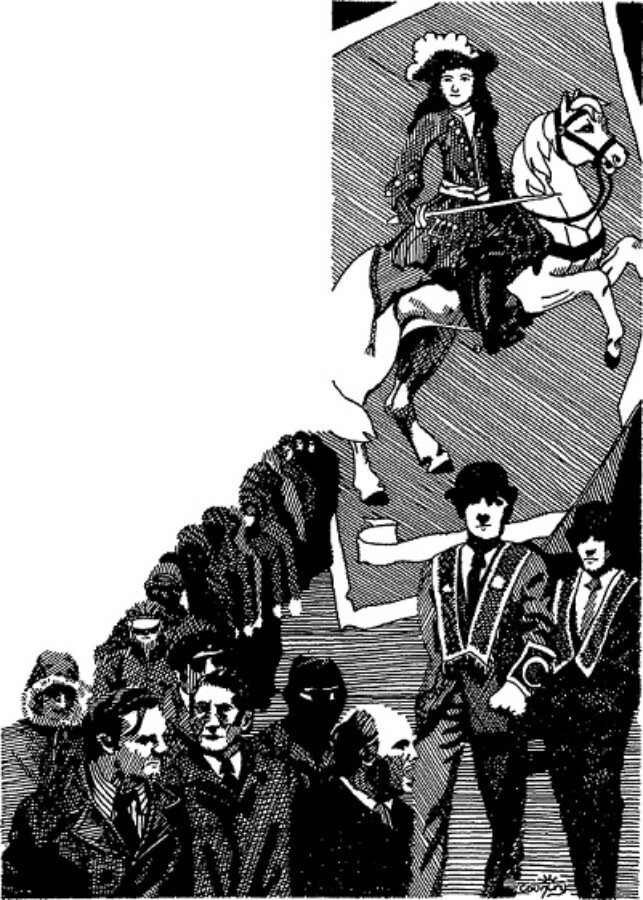

I rode a bus to the field with some of the women and children from Cranston. A Cranston grandmother sang, "I'd rather have a n***** than a taig [Catholic]." [spelled out in full in the magazine] Cries of "kick the Pope" punctuated the singing, sounding more like a football chant than a call to violence. At the field we perched on a stone fence and watched the three-hour procession file past. Hundreds of men wearing orange collars, black bowler hats, and Sweet William boutonnieres marched behind banners emblazoned with Queen Victoria, King Billy on his white horse, or slogans proclaiming "Temperance." Crowds lined the road. Bands played Loyalist tunes; the big Scottish Lambeg drums were stained with the blood of the drummers' wrists. The field looked like the aftermath of a battle, littered as it was with the crumpled bodies of exhausted men. Concessionaires sold "poke cones" and patriots hawked the Red Hand of Ulster, printed on cardboard and stapled to red and blue ribbon like a country fair prize. It was difficult to separate the political implications from the carnival atmosphere.

A less festive observance occurred a month later, on the fourth anniversary of internment, a policy allowing the Government to detain without trial people suspected of terrorist activities.

(The practice has since been stopped and the detainees released.)

The anti-internment sentiment was expressed most strongly in the Catholic areas, where people paraded to demonstrate support for "the men behind the wire." By the following evening a huge cloud of smoke hung over West Belfast, where trucks and cars were burning in the streets. A gun battle between snipers and the army left three men and a five-year-old girl dead. At Cranston we watched the smoke and gunfire on the evening news.

"Look at the wee dog. Och, the poor wee dog," Mrs. Douglas said over and over, referring to a tiny animal that had wandered into the fray. The neighbors were listening to their police radio and worrying that this would trigger a new wave of violence.

"After two years," signed the mother, "it was so nice to start going downtown again."

"When will it end?" I asked a UDA man.

"It won't," he replied.

The following week brought a series of tit-for-tat bombings that killed eleven people, shook the fragile IRA cease-fire, and flashed Belfast street fighting onto television screens around the world.

I met a wide variety of people in Belfast: students, workers, the wealthy, the unemployed. A few preferred to ignore the conflict, clicking off the news when violence was mentioned and insisting that things were "not that bad." Many, though they might listen dutifully to the latest government negotiations, expressed the sad conviction that there is little hope.

Some think that the problem has gone beyond religious or political loyalties. They suggest that while people are capitalizing on the conflict through intimidation and protection rackets, the troubles will not end. A Protestant lawyer put it this way: "A criminal element has taken hold of the country. People who in ordinary times would be considered hoods and thugs have somehow gained the upper hand. You can see this on a small scale at places like Cranston."

Perhaps the conflict in Northern Ireland is best expressed by a new play, We Do It for Love (by Patrick Galvin). In a summer premiere at Belfast's Lyric Theatre the play sketched the people of Belfast. Protestants, Catholics, soldiers, prisoners, and children revolve around the central and abiding prop, a merry-go-round.