WORLDVIEW Magazine ran from 1958-85 and featured articles by political philosophers, scholars, churchmen, statesmen, and writers from across the political spectrum. Find the entire archive online here.

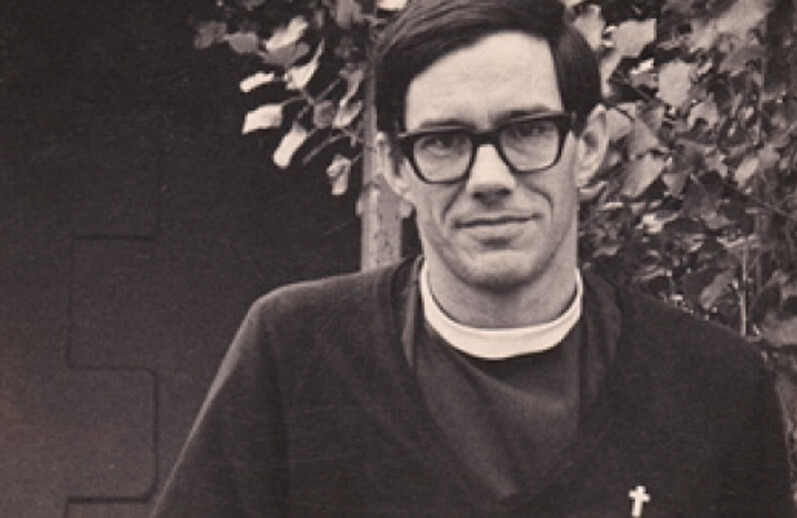

David Russell was a courageous white South African Anglican priest. On October 19, 1977, the government cracked down on the press, organizations, and individuals who fought apartheid. Russell was put under house arrest and forbidden to publish. He and his sister circumvented the ban via this interview, which includes his description of what it's like to live on 5 Rand a month (approx $6), which he did in solidarity with black South Africans. October 19, 1977, was described by one of South Africa's best known newspapers, the Rand Daily Mail, as "the bleakest day in South Africa's history." On that day the government banned the country's only black newspaper, The World, eighteen organizations (including most groups in the Black Consciousness Movement that had come to be associated with the name of Steve Biko), and seven individuals. Forty-two black leaders were imprisoned without trial, nineteen homes and offices were raided. "What it has done," wrote the editor of the Mail, "is to leave the Black people who reject separate development with no outlet, no organization, no mouthpiece even, through which to express themselves." And so it remains today.These repressive measures were widely publicized and condemned throughout the world. With the exception of Donald Woods, the banned editor of the Daily Dispatch newspaper, who escaped the country, addressed the United Nations, and published the first book on Steve Biko, few people outside South Africa know who these people are, why they were imprisoned or banned, how it feels to be outlawed in these particular ways in that particular country. The law permits the government to ban and detain people indefinitely without explanation, trial, or recourse of any kind. And, since it is illegal in South Africa to describe conditions in prison without the consent of the director of prisons, and illegal for banned people to publish, or even to be quoted orally or in print, it is not surprising that so little is known.

As the twin sister of one of those banned, l returned to South Africa to visit my brother in January, 1978, breaking a personal twelve-year boycott of the country. My brother was one of only seven whites included in the primarily antiblack repression of the previous October. There is conspicuous racism even in the manner of repression: All forty-two blacks were detained for a year in prison, while the seven whites were "banned"—a punishment described in detail shortly. Furthermore, for black people time in prison can be fatal. Since 1962 there have been about forty deaths of blacks while in detention. In the last couple of years the rate has climbed to about one a month. And torture of black people in prison has been an instrument of policy for a long time.

My brother, David Russell, a forty-one-year-old Anglican priest, was the only person on that fateful October 19 who was placed under semi-house arrest in addition to being banned. While the banning order forbids his being quoted inside the country, this restriction does not apply outside South Africa. However, it is illegal for an article written by him to be published anywhere in the world. The interview format, therefore, becomes the only way he can communicate directly with an international audience.

DIANA: What does banning actually entail?

DAVID: Banning orders prevent a person from attending any "social gathering"—defined as more than two people. Being able to meet with only one person at a time obviously precludes any normal social life. Also, we can't attend any formal meeting, defined as "any meeting with a common purpose." There are often special additional restrictions; for instance, in my case I can't go into so-called African areas, colored areas, or Asian areas. I can't go to any educational institution. A banning order also confines one to a particular district. And a banned person cannot have anything whatsoever to do with publishing. So one is silenced.

And what is house-arrest?

There can be a very tough twenty-four-hour house arrest order which amounts to imprisonment in one's own house. But twelve-hour house-arrests are more common. These usually enable the person to continue to earn a living. In my case I'm under house-arrest from 6 P.M. to 6 A.M. Mondays to Fridays, and all day Saturdays. I am allowed out on Sundays from 8:30 A.M. till 9:30 P.M. The assumption, I believe, is that I will be taking services on Sundays. House-arrest also restricts one's visitors. No one can visit me at my home. But I can meet people one at a time at other locations during the times I'm not restricted to my house.

Why were you banned?

The government carefully watches people who speak out against the system. They don't ban priests easily; they don't want to ruffle the church as an institution. But I think they've been watching me from the time I began exposing the horrendous conditions in the resettlement township, Dimbaza, near King Williamstown, where I lived.

Tell me more about that.

It was Verwoerd, [prime minister, 1958-66] who evolved the Bantustan system in which traditional African areas became Bantustans, or Homelands. These Homelands comprise only about 13 per cent of the country, while the Africans comprise 70 per cent of the population. Increasingly, it has become a more vigorous aspect of government policy to try to get the Africans into these fragmented, poverty-stricken reserves. This vast removal plan has been going on for a long time. As the government began to systematize this plan, they saw the need to create "rural villages." They would find a place like Dimbaza and start building very cheap houses. The people sent there were often pensioners, widows, a lot of old people, whom a deputy minister once actually referred to as "superfluous appendages." In effect, these people were dumped into a place with no work and with very meager rations. The few who did have work received a totally inadequate wage. The result was disease, malnutrition, and death. The number of children who died became scandalous. It was a terrible situation—people had no heat because they had no money for firewood. Their rations frequently ran out before the month was up. It was absolutely tearing—the poverty and the suffering, the destitution, the callousness of deliberately putting people in that position. It's quite clear that the government would not have treated whites in this way.

Africans received a miserable amount for a pension—only 5 Rand [about $6] a month. Whites at the time were getting 41 Rand [about $50] a month for their pensions! For some reason this miserable pension became a symbol for me. I felt a challenge to try myself to live on 5 Rand a month as a means of drawing attention to this racist double standard. I decided to publicize the situation by writing a monthly letter to the government minister concerned, describing what it was like to live on that amount, then mailing a copy to the press.

On April I 4, I972, I started off on a very austere diet, which I continued for six months. The 5 Rand had to cover fuel, clothing, and any other needs I might have, as well as food. I would never claim to know what it was like for the black people who had to live on this amount—I knew that I was doing it for a purpose. It wasn't as if I were trapped in that poverty. If I became desperate, I could go to my friend next door and get a decent meal. If I wanted to opt out, there was always that possibility. Also, six months is nothing compared to a lifetime. So the whole psychological situation and experience for me was totally different.

Did your monthly letters to the minister get much publicity?

Yes, they were widely printed in the English-language press. Dimaza became very well known, and many people visited to see it for themselves. They were horrified that people could be treated like that. I like to think that this public expose helped in some small way to stem the pace at which these Resettlement Town ships were popping up.

By the end of my five years working in Dimbaza, the absolute destitution of the place had been supplanted by a certain cushioning of conditions. There were more schools. A doctor came. There were fewer deaths. A public telephone was brought. An ambulance service. Teachers. More people working. So it wasn't the ghastly scandal that it had been.

How was it to live on 5 Rand a month?

I had weighed about 165 pounds. My lowest weight went down to about 145 pounds, which wasn't a fantastic loss. It wasn't a starvation diet. But to get what little food value there is in the staple cereal of most Africans you have to eat a tremendous amount. I ate a whole half-loaf ravenously every second day and I would still be hungry. I kept in reasonable health, though I felt very weak and listless. It was terribly boring. I longed for a change. I became completely food-oriented and not interested in very much else. I looked forward all the time to the six months ending. October 15, 1972, was one of the most joyful days of my life, when I could eat some nuts and other goodies. ·

Why do you think you specifically were singled out for house-arrest in addition to banning?

I think it was vindictiveness on the part of the Security Police. Their main concern was to keep me out of black townships, but the banning order alone does that. They were particularly angered by my involvement in exposing the actions of certain members of the Riot Police in the killings and burnings in the Nyanga townships outside of Cape Town over the Christmas weekend in 1976. Some of the Riot Police had incited a particular group of black migrant workers, encouraging them to burn other black people's houses. The police opened the way by shooting at residents.

Somebody witnessed two Riot Policemen going into a house and bringing a struggling person out and letting him get chopped up and killed. A woman described how the Riot Police vans had come in amongst the houses, going very slowly. A policeman was sitting on the front of a jeep, with a gun, beckoning others to come. An old man passed the woman's garden, walking across an open space. He was shot at for no reason, and fell to the ground, bleeding. The Riot Policeman sitting on the hood pointed to the bleeding man, and a group of people came and finished him off.

There was another account of two Riot Policemen in the grounds of someone's home. A group of people came in and started to chop up a woman's mother with some sort of ax. The woman was screaming that her mother was being killed, and the Riot Policemen just stood watching.

So what did you do?

The Minister's Fraternal, a group of largely black ministers and priests who were working in the black townships, got together. We decided to record what had happened and to publish these accounts of violence. Our publication was promptly banned by the government. We were accused of producing undesirable literature, and we were found guilty of this offense. The police tried to intimidate and divide us, to threaten us, to get contradictory statements from us, and to cover up the accounts we had published. The government's utter refusal to face what had happened in the Nyanga township made me all the more determined to persist in publicizing it. I decided to produce another edition based on other similar eyewitness accounts. [The two documents mentioned here have been published by the United Nations.] I sent this report to the press, to religious leaders, and to every Member of Parliament.

The police were absolutely wild that they weren't able to cover this up. Quite a bit of it got into the press. I think that's what made them decide to slap me down with a house-arrest order. Also, they didn't like what I was doing with others to expose the dreadful conditions in the black squatter townships. In its effort to get rid of Africans from Cape Town, the government decided to simply demolish one of the squatter camps called Modderdam. Bulldozing started in the winter when it was cold and raining. People had nowhere to go for shelter or to set up new houses, so an emergency meeting was called. Some young people said, "One thing we can do is all go down tomorrow and stand in front of that bulldozer." There was a show of hands, and it looked as if a lot of people were into doing that. The next day a hundred people came to the camp. We waited for the bulldozers but they didn't come. Obviously, the authorities were thinking, "This lot will get tired and go." It turned out that later that same afternoon the bulldozers came and started the demolition.

I received a phone call that night informing me that the place was pretty well flattened. In spite of this I felt committed to being there the next day. So at half-past seven in the morning I went to the camp. Two others were there, and we walked into Modderdam. The devastation was like the aftermath of a bomb. It was also very quiet, like the lull-before-the-storm. Police vans arrived and parked across the other side of the road. A ghastly great animal-like machine came—a front-end loader. We walked toward it and went and sat down in front of the wheels. A policeman shouted, "Vat hom, vat hom!" ("Take him, take him!"). Then I was lifted up and taken.

We were subsequently charged with trespass, with obstructing the authorities in the course of their work, with resisting arrest, and with riotous assembly. We were taken along to Bellville Police Station, where we spent the night before appearing in court the next day. The case was remanded to a few weeks later, on certain conditions of bail, one of which was that we wouldn't go back to Modderdam. I said, "I can't agree to that. My conscience might require me to go back." So l went to jail.

The case came up on the 21st of October, 1977. I had been banned just two days earlier. We pleaded guilty of obstructing, and were fined 100 Rand [about $120].

What sort of publicity did this get overseas, and in South Africa?

It got some publicity overseas, and quite a lot here. But the government appeared to decide that, much as they hate the publicity, they had to get rid of the squatters. They weren't going to accept the principle of black workers being permitted to settle here with their families. So after Modderdam they demolished a place called Werkgenot, then Unibel. About 25,000 people were affected.

What has helped you most to deal with this experience? I have felt upheld by my faith, by my convictions, and by the support of friends and family, and by the knowledge that I am but one of many. Also, I see that my house-arrest order and banning is nothing compared with those in detention at this time, with the terrible threat of torture so many blacks have to live with.

Does much right-wing terrorism occur in South Africa?

These tactics are used a lot, in particular against white people who go against the prevailing mores of the white community. Sick things are done. For example, to Basil Moore, an ex-Methodist minister. They skinned his children's cat and left it on their front doorstep. For myself, it started when I was living in King Williamstown and working in Dimbaza. I received threat letters from so-called anti-Communist organizations. They enclosed drawings of daggers dripping with blood. And one morning I found my tires punctured.

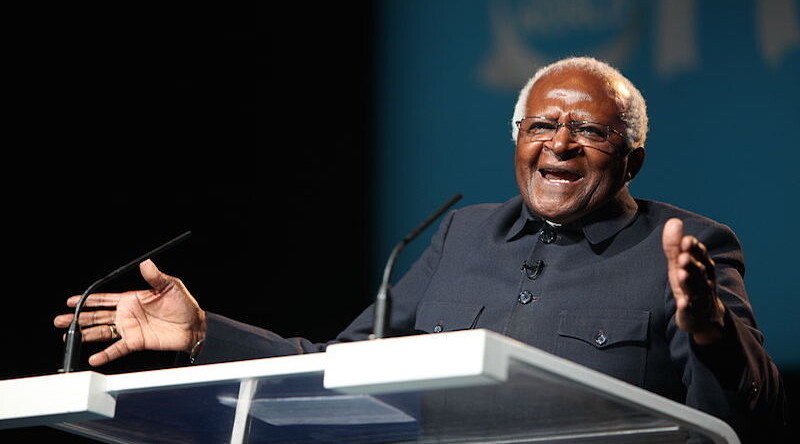

How did you come to be friends with Steve Biko?

I had known him for a long time. His parents' home was in King Williamstown. They were among my parishioners. So when he visited them, he'd visit me too, and we had long talks. Then he was banned to King Williamstown. I was glad to be able to be of some help to him in providing him with an alternative base to his home, because he wasn't allowed to receive visitors there. I was living in a little house on the grounds of an old dilapidated church. We turned the old church into an office block, and Steve was able to develop a base there.

There was a very high level of trust between us. It was more than a political bond, it was a friendship as well.

How did you feel personally about his death? At first I was stunned and numb. It was totally unexpected. I thought they would be more careful of him than that, since he was well known. However, for me and many others Steve's death deepened our commitment. It was a matter of, "Well, Steve, you're not going to die in vain. They are going to regret your death. Your death will be fruitful. What you stood for will grow." Often when I'm hit by something, or feel deeply angered by what the government is doing, as in Dimbaza, my response is not to weep but to be even more determined to do something with my life to change it. So it was with Steve's death. It sharpened my commitment. I also felt, "Well done, Steve! You lived totally for the cause, and you died for it. And they never stopped you living for it, in the sense of breaking you and getting you to deny what you stood for. Your victory is sealed."

The way he died and the consequences of his death had certain analogies for me to the Christ event. The inquest revealed the utter degradation he endured. His being taken there naked. This free, seemingly indestructible person being beaten down and dying in such an undignified way, but subsequently having such a remarkable effect on so many people. He has become a worldwide symbol—and affected people one never expected would be affected.

BREAKING THE BAN

In early December, I979, David Russell deliberately broke his banning order to attend the Anglican Synod in Grahamstown, three hundred miles from Cape Town. As an elected delegate to the Synod, he decided to place the calling of the church above the unjust restrictions of the state. For this he received a standing ovation at the Synod. The archbishop of Cape Town, Bill Burnett, the leader of the Anglican Church in Southern Africa, subsequently told the Synod that he was "prepared to see church defiance of the government lead to an end of the institutional church." According to the South African Press Association, "Clerics likened his [the archbishop's] message to what took place in Germany under the Nazis, when the church as an institution felt it could no longer continue in the face of state repression...."

The reaction of the government and court has been quite otherwise. On February 26, 1980, Russell was sentenced to a year in jail, and three-and-a-half years of suspended sentences for five years, for breaking his banning order by attending the Synod. On March 3, 1980, Russell's attorney filed an appeal against the severity of the sentences. After four days in jail Russell was released on his own recognizance. The appeal will be heard in the Supreme Court sometime in the future.

The fact that a priest can be given a four-and-a-half year sentence for simply attending a Synod highlights the iniquity of the whole banning system in South Africa. There has already been considerable criticism in the South African press of the government's actions against Russell. However, international pressure criticizing this vindictive method of trying to obliterate all opposition would likely be far more effective. More people need to recognize that the antiapartheid struggle is an international one.